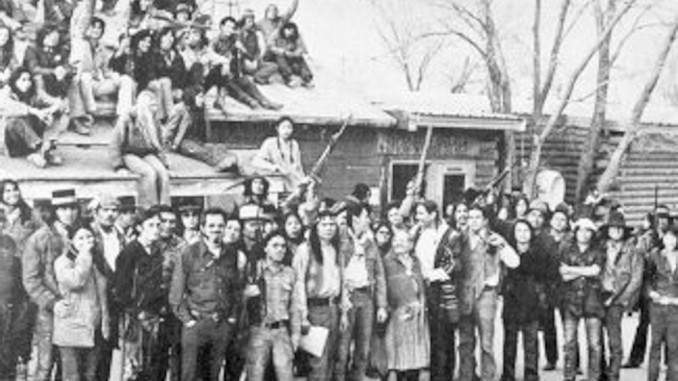

On February 27, 1973, activists from the American Indian Movement (A.I.M.) initiated a takeover of the tiny town of Pine Ridge, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The takeover intended to call attention to the oppression and miserable living conditions of Native Americans on the reservations, demand the U.S. government live up to its treaty obligations (specifically the 1868 Treaty of Laramie), and called for the removal of the corrupt and brutal reservation officials. The location was the same town where in 1890 U.S. cavalry troops slaughtered 300 Oglala Lakota people in the Wounded Knee massacre. For 71 days more than 200 armed A.I.M. activists occupied the town, attracting the eyes of the world to the northern plains.

The Oglala Lakota (often called the Sioux) had a long history of resisting first the white expansion into their territories, then the U.S. government restrictions that came to shape their lives. Former leaders like Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Crazy Horse had led resistance to U.S. military incursion, most famously at the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn in present-day Montana. The famous Ghost Dance that was practiced in that period was directly in response to the challenges of U.S. colonial incursion, and sparked U.S. military action that culminated in the Wounded Knee Massacre.

But after the massacre at Wounded Knee, the Oglala Lakota reluctantly acquiesced to the dominating power of the U.S. military, and in the early years of the 20th century they were enclosed on the Pine Ridge Reservation. They were left with limited land and resources, condemning them to lives of dull rural poverty. Over the decades, tribal leaders on the reservation started behaving like corrupt politicians, padding their pockets while providing only the most basic services to their constituents, and sometimes relying on violent coercion to intimidate people to support their rule. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Pine Ridge Oglala Lakota had had enough, and wanted their despised chairman Dick Wilson gone.

A.I.M. was formed in 1968 with the larger goal of Native American liberation. Some members had already participated in the occupation of Alcatraz Island from 1968 to 1971, and in 1972 A.I.M. itself occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters in Washington, D.C. The people of the Pine Ridge Reservation asked A.I.M. for help, and the idea of the occupation was hatched.

The 1973 occupation was intense. The A.I.M. activists barricaded entry points to the town and maintained security points. F.B.I agents and Federal Marshals blockaded entry to the area, not allowing in any food or medicine. On dozens of occasions they engaged in nighttime firefights with U.S. agents, in which at least two of their members were killed. Some of these firefights were actually started by thugs paid by Wilson to get the government to invade the town and crush the A.I.M. movement. One activist and veteran described the conflict as “just like Vietnam.”

Direct negotiations took place on and off throughout the occupation between A.I.M. representatives and representatives of the U.S. government, but from day one the government negotiators refused any demands, and only softened their stance slightly as time went on. A.I.M activists did not all agree on their daily tactics or their larger aims, and neither did the larger Native American community nationwide, which made it more difficult to unite all of their forces into one common fight. In early May, tired, hungry and outgunned A.I.M. activists called an end to the occupation. They had achieved none of their concrete demands, and for the next few years its leaders had to undergo trials and public controversy before being acquitted.

But despite the lack of concrete progress on their initial demands, A.I.M. activists and thousands of other Native Americans felt proud of their action. Along with the Alcatraz Occupation and other smaller actions, the movement fostered a sense of pride and initiated a new tradition of struggle. Len Foster, one of the occupiers, described the effects of the occupation this way:

“Wounded Knee opened a lot of hearts and minds to what oppression we were suffering. We were downtrodden, oppressed, made to feel ashamed. We were told to cut our long hair, not to participate in ceremonies, to become Christian and burn our medicine bundles. All the decisions we made at Wounded Knee affect our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.”

Today, despite the superficial prosperity of some Native American tribal organizations, we know that working class Native Americans are still among the poorest, most oppressed peoples anywhere in the United States. They suffer higher rates of poverty, unemployment, alcoholism, and incarceration than any other racial or ethnic group.

We also know that United States colonialism in North America was genocidal, and that U.S. imperialism still exercises enormous power to oppress and dominate around the globe. Whether keeping indigenous Americans on reservations with little to no real opportunity and little freedom, or supplying the Zionist Israeli state with the military might needed to carry out its genocidal attack on Palestinians today, U.S. imperialism has no limits to the level of brutality it will resort to in order to maintain the status quo.

But the freedom fighters of A.I.M. in the 1960s and 1970s showed that people can fight back, just as Palestinians did in the first Intifada of 1987 and continue to do today. We can learn lessons from these struggles, and draw inspiration from the willingness to stand up to oppression anywhere. And we can mobilize and broaden our forces against the brutality of U.S. imperialism everywhere.

For a brief overview of the occupation and its larger context, these three video excerpts from the PBS documentary We Shall Remain provide a good introduction: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.