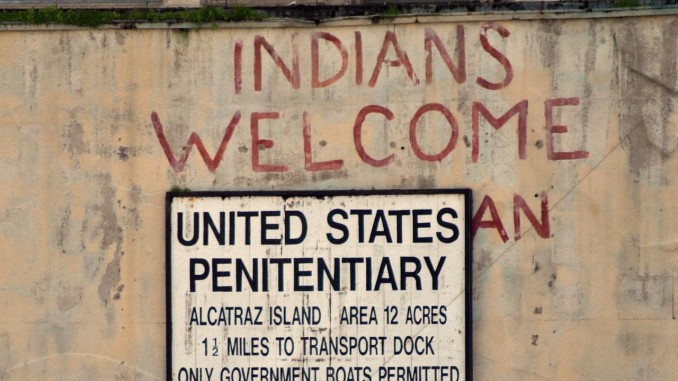

Pre-COVID-19, many American Indians along with people of many backgrounds have celebrated Unthanksgiving Day, also known as the Indigenous Peoples Sunrise Ceremony, on the fourth Thursday in November. This is an annual event that takes place on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay, coinciding with Thanksgiving, designed to honor American Indians, promote their rights, and to mourn and honor their lost ones.

The event on Alcatraz Island commemorates most especially the 19 months, from November 20, 1969 to June 11, 1971, during which a group calling themselves Indians for All Tribes (IOAT) occupied Alcatraz Island and its infamous prison that had been empty since 1963.

They did so under the 1868 Treaty of Laramie, which had been violated by the U.S. government in the 19th century, and which they argued gave American Indians the right to all abandoned, retired and out of use federal lands.

They decided on the occupation to challenge the Termination Policy of the U.S. government, a policy proposed in 1953 to completely abrogate approximately 350 still existing treaties, end the existing Indian reservations, and close the Bureau of Indian Affairs. All of which, while paternalistic and constraining, nonetheless protected indigenous peoples from further encroachments and depredations by white Americans.

The event that sparked the plan for the occupation was the 1969 fire that burned down the San Francisco Indian Center, where American Indians had previously gone for social events, job leads, and legal and health services. That loss spurred activists to pursue an aggressive push to obtain Alcatraz Island as their own.

On November 20, 1969, 89 activists, many of them students, representing dozens of Indian groups, sailed to the island in small boats and began the occupation. Upon arriving, they read a proclamation aloud to the press, entitled a Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His Peoples. In it, they offered to buy the land back from the federal government (at 19th century prices!), and argued that it would be suitable as a new reservation, since it was just as poorly equipped and maintained as the already existing reservations.

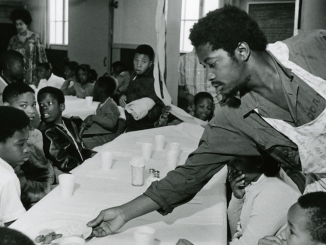

It began with 89 occupiers, but within months 400 Native Americans activists were living on the island. Despite the obvious challenges of maintaining a community on an island detached from direct supplies and subject to blockade by federal forces, they survived on donated food, they cooked in a communal kitchen, and they managed a health clinic and a small school. Moral and financial support came not only from thousands of Indian individuals and groups, but from celebrities like Jane Fonda and Marlon Brando. According to one participant, over the course of the occupation as many as 15,000 people, mostly Native Americans, visited the island. For many American Indians, Alcatraz island became had become a symbol of freedom, and its occupation a symbol of what they could achieve.

The federal government was initially hostile, and never seriously considered turning the island over to Native Americans. But the occupation clearly exerted pressure, and eight months after the occupation began, in 1970, Republican President Richard Nixon ended the Termination Policy, affirming the rights of American Indians to self-determination on their lands, and even opening new lands to American Indian control. In the following years, Congress extended and deepened Indian rights to self-determination. As one occupier argued, it is likely that “if it wasn’t for Indians of All Tribes in ending Termination…the conquest would have been complete.” Another said “We saved the Indian Reservations of this country by virtue of that action.”

Despite these successes, the challenges faced by the occupiers grew as time dragged on. They were not all united around goals and tactics, some of the leaders had contradictory methods that caused conflict, and support fell away as the occupation left the news. In May of 1971 the federal government cut all power and water, in the end less than 15 occupiers remained, and they were removed by federal officers on June 11.

While some Indian groups criticized the reforms achieved by the occupation as small changes that left the larger structures of colonial control in place, the occupation of Alcatraz nonetheless showed what organized, collective action can achieve. It was the first time representatives of a large number of Indian nations had joined in a joint action, and therefore showed how different groups can come together. Participants went on to lead future actions – including takeover of the Mayflower II, the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties, and the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee – for which the Alcatraz occupation was often viewed as an inspiration. As an older activist remembered, “this is the first move that Indians have made, in my lifetime, to try to change the conditions of their people.” For that reason alone, it held great symbolic importance for all American Indians.

As we experience the holidays this year with friends and family (albeit in socially distanced fashion), it is worth remembering the struggles American Indians have carried out to maintain what little they have. Even in recent history, in places like Standing Rock, North Dakota, it has been only mass struggle that has kept their lands from being completely overrun by the insatiable demands of capitalist development.

While the many of the battles waged have been defeated, some have pushed back courageously against colonial encroachment, and we can take lessons from those fights, and use that knowledge in the future to organize more effectively, and on a larger scale, in order to build the forces needed to bring justice to the American Indians.