On August 17, 1985, workers at the Hormel meatpacking plant in the small town of Austin, Minnesota began a strike that lasted just more than one year. In the course of the strike, the approximately 1,500 workers who struck, and much of Austin’s population, generated a strong, united fightback against corporate greed and union concessions. They captured the attention of other workers in the U.S. who were inspired by the strike. But the strike also showed the limits of what one small group of workers can do when going up against a major corporation as well as their national union bureaucracy, and trying to win within the limits of the legal contractual framework.

UFCW Bureaucrats and the Rank and File Response

The period from the late 1970s into the 1980s, saw a number of unions either lose strikes outright, or agree to give huge concessions on everything from wages to working conditions to benefits. Rather than fighting these trends by organizing locals to fight back together in the meatpacking industry, the national leadership of United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) agreed to concessionary contracts. The workers of UFCW Local P-9 in Austin had already given concessions. In 1978, Hormel threatened to close the Austin facility unless workers gave back $12,000 each towards building a new factory. The union officials agreed and signed a seven-year no-strike pledge.

When the new plant opened in 1982, many older workers retired, and by 1983 two-thirds of the plant’s workforce consisted of new hires. So, it was a very different group of workers than in the past period. The workforce was reduced, yet production was increased by 20%. In an industry in which worker injuries were already common, the injury rate in the Austin plant increased to six times higher than the industry average!

Shortly after the opening of this new plant, other meatpacking companies imposed wage cuts, either closing union plants and reopening them as non-union plants or negotiating pay cuts under the threat of more plant closures. Oscar Meyer, another major meatpacking company, negotiated reductions in wages for their workers. Then in March 1984, Hormel negotiated a new contract with UFCW Local 431 at their Ottumwa, Iowa plant, with a wage cut from $10.69 to $8.75 per hour and an agreement to lay off hundreds. This new contract agreement required three rounds of voting to get the local to agree to it.

Then in September of 1984, the officials of the national UFCW allowed Hormel to reopen their contract with Local P-9, rather than waiting for it to expire in 1985. Jim Guyette, the president of local P-9, openly opposed this action. Guyette had been hired in the late 1960s, and was part of a newer generation of workers who didn’t think that collaboration with management was working, and who wanted their union to be more assertive. He became active in the local by opposing concessions in the ‘70s, and then was elected to the local executive board in 1980. Continuing to stand against concessions and making the case that the workers needed to stand up for their families and community, Guyette won the presidency of the union in 1983.

Guyette and many of his supporters decided that they would not accept a contract that included any of these concessions. Instead, they proposed to take Local P-9 out of the company-wide negotiations between the UFCW and Hormel, and to go through negotiations alone. This was, of course, not ideal, and some workers, particularly older ones, were opposed. The local was facing a company determined to impose concessions, and a national union leadership unwilling to organize its full strength to make a larger struggle.

The Strike Begins

In response to this move by the local, Hormel instituted a wage cut at the Austin plant from $10.69 to $8.25 per hour. The company also retroactively cut health care benefits. This suddenly put some workers in debt to the company for care they had already received under the full coverage they had months earlier. The workers of Local P-9 had had enough, and they said a loud “NO” to the company and to the bureaucrats of the UFCW national office who advised them to take the cuts. They voted to strike. The workers had decided that they were going to take a stand and organize themselves to defend their jobs and their families.

The national UFCW officials approved the strike, but only on the condition that Local P-9 would not expand it to other plants, thus cutting off what would have been the best way to put pressure on Hormel. This forced the leaders of Local P-9 to look elsewhere for support. Guyette looked into hiring a public relations firm to help publicize the strike against Hormel. Then he read about Ray Rogers and the Corporate Campaign Incorporated (CCI) in Business Week magazine. He decided to contact Rogers to see if he would help P-9. Rogers, a longtime labor activist, had helped union members win a victory against a major textile firm in the South in 1980, a victory popularized in the movie Norma Rae.

In October 1984, Rogers gave a presentation to Local P-9, and they wanted to hire him. UFCW President William H. Wynn announced that the UFCW would not be hiring Rogers. But Local P-9 ignored this and went ahead and hired Rogers and CCI. They approved a weekly $3 per member fee to cover the consultant’s cost. This decision deepened the already existing divisions between P-9 and the national union. The local used the corporate campaign publicity to try to shame the company and other businesses that supported Hormel. This was aimed primarily at the bank that handled all Hormel’s finances. They urged people to boycott Hormel products in support of the strikers. This Corporate Campaign put forward the idea that the corporate powers were all allied against the workers, so workers also had to be allied together to support P-9. This helped with sympathy outside of Austin.

Workers Organize the Strike

Immediately, when the strike began, the local organized a number of committees to involve as many workers as possible in decision-making. They set up a Communications Committee, a War Room for coordination of activities, and even a support program they called the “Tool Box” to help individuals and families through the stress and emergencies of the strike. The United Support Group of spouses of P-9 members, which had previously existed, went into full activity. The union hall was open 24 hours a day, and basic meals were served.

Family members, retirees, high school students, even many local small businesses formed groups to support the strikers. During the Christmas holiday, townspeople made toys for the children of striking workers. It is not an exaggeration to say that nearly the entire town of 24,000 people stood in spirited solidarity with the striking members of P-9. This in a town where for decades the company had shaped the local economy and used its propaganda to try to keep its workers in line.

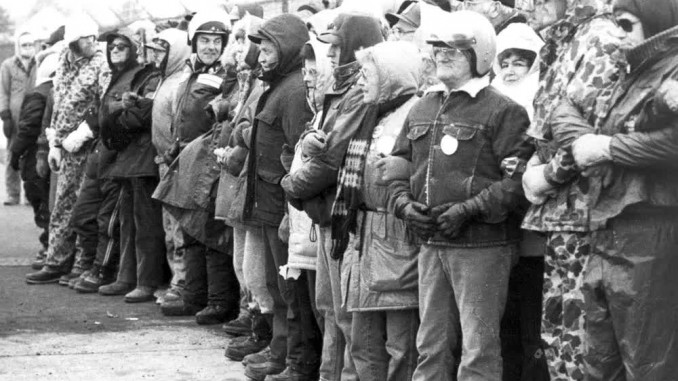

Most strikers went to the picket lines daily, sometimes in the dark, and in sub-zero temperatures. They used their cars, and later their bodies, to block entrances to the plant against police, state police and later national guard forces.

The workers reached out to other unions and got statements of solidarity, occasional visits from other unions, and support from a variety of small leftist organizations. Union locals and individual workers took collections for P-9 at factory gates in Chicago and other cities. These visits, statements and donations showed that working people around the nation stood with the strikers. Millions were sick and tired of concessions to powerful corporations. The local sent hundreds of worker representatives throughout the Midwest to tell their story and win support. And on many occasions, hundreds of supporters from other unions traveled to Austin, and joined the P-9 picket lines and marches. On at least one occasion, this generated a march of more than 5,000 mostly working people – a huge number for such a small town.

Battles Against the Company, the State and the Bureaucrats!

But, despite this spirited willingness to stand together and fight, and despite the show of support from other workers’ organizations, the P-9 struggle remained localized. This was a key problem from the start. While they did appeal to other workers, unions and other organizations for donations, visits of support, and at times boycotts, Local P-9 did not see the possibility to expand their strike and generalize their struggle.

Although they were able to shut down production in the Austin facility, Hormel continued to produce and even increased production at their other 10 facilities. Since the company was not being severely damaged by the slightly reduced production, they were able to wait out the Austin strikers.

Five months after the strike began, Hormel attempted to reopen the plant using scab labor, that is, a workforce hired for the purpose of replacing striking workers and defeating the strike. Local and state police and even the national guard were called in to escort scab workers into the plant. In the dramatic first days when scabs were escorted into the factory, strikers and supporters clashed with Minnesota state police and national guard in the snowy cold outside the entrance to the factory. This fight was covered on the national TV news and was widely seen with shock and surprise by workers around the country.

P-9 strikers also faced the problem of workers who agreed to scab, themselves poor people without good jobs just trying to make ends meet. The tensions were deep and the conflict divided friends and families. Within days, more and more scab workers began entering the factory, slowly increasing production.

Company and UFCW Bureaucrats Move to Crush the Strike

Even then, the strikers refused to give in. They doubled down on asking consumers to boycott Hormel products. And they finally began to look outside of Austin for active strike support from other Hormel workers. Local P-9 openly called on workers, and union locals, at other Hormel plants to strike in sympathy. They also sent roving pickets to those locations.

The company immediately threatened other workers that anyone who joined in a sympathy strike would immediately be fired. In the nearby factory in Ottumwa, Iowa, hundreds of workers did strike in sympathy. In response, 507 workers were fired and part of that factory closed. This was a big blow that discouraged other workers from supporting P-9, and further demoralized the Austin workers.

In March, the UFCW national officials withdrew their approval of the strike and cut off the $40 weekly strike benefits to each worker. Even then the workers of P-9 refused to give in. At a mass meeting of 900 in March, they voted overwhelmingly to continue the strike. They also continued to reach out nationally for more union support.

In May, the UFCW national officials put Local P-9 into receivership, and took over its union hall. They also began negotiations with Hormel, over the heads of the workers and local leadership. At this point the workers were demoralized and divided and the local was crumbling. Some workers trickled back to work, while many quit or were fired. But hundreds still remained on strike and picketing continued.

In early September, the UFCW national officials presented Austin workers with a concessionary contract that they had negotiated. Seeing no other choice, the workers voted overwhelmingly to accept it. So, this long and determined struggle ended up as a defeat.

The Real Lessons of Hormel

The primary reason Local P-9 lost their struggle was because their fight remained isolated at one plant, in one small town. Even though Hormel employed more than 10,000 workers in all its plants, only approximately ten percent of its workers were actually on strike. Throughout the strike, the company was able to keep the vast majority of its production going, which kept the profits rolling in.

For a local like P-9 to have had the best chance to win the strike, it would have had to broaden the struggle. They needed more fighting forces at their side. Of course, actually organizing that in 1985 was really difficult. For decades, the union movement had been in decline, and accepting concessions had replaced a fighting strategy.

But there is a real history of working-class struggles in the U.S. It was how the working class forced the capitalist class to back off in the 1930s, in response to the attacks against the workers as a consequence of the Great Depression of 1929 and the period that followed it. These struggles were part of the construction of a new type of workers’ organization. Instead of unions based on narrow skills or on employment in just one workshop or factory, they brought together skilled and unskilled workers on an industry-wide basis. These newly formed industrial unions grew to have hundreds of thousands of members. When well organized and democratic, these workers could bring production to a halt across entire industries, win economic victories that improved their lives and work, and showed the power of the working class. These unions were in the process of becoming the Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO.

In 1934, militant general strikes in Toledo, San Francisco and Minneapolis launched a working-class movement that brought together workers from different workplaces and industries. They fought off police and national guard, and they even took over factories and shut down portions of cities. In 1936-37, workers in Flint, Michigan did the same in a general strike that enveloped numerous factories and the entire city. And in 1946, nearly five million workers went on strike nationwide, winning huge victories and enormous gains for workers in many industries. These generalized movements were able to bring together tens of thousands and in some cases millions of workers, really changing the balance of forces in the workers’ favor.

Some of these union movements and strikes in the 1930s and 1940s also benefitted from the presence and influence of socialist and communist activists. They were not only among the most active members and most committed fighters, but they also brought an analysis of history and capitalist society that provided a framework within which to develop strategies and tactics that might win their struggles against the bosses. This was especially true in Minneapolis in 1934 and Flint in 1936, where socialist revolutionaries were among the leaders of the rank-and-file workers who successfully struck and won. These revolutionaries helped the union movement to become more militant and to fight in new ways that enabled it to win.

After the massive strike wave of 1946 that won victories for millions of workers in the U.S., the unions lost the dynamism and militancy that had allowed them to win those victories. After World War II, and with the Cold War period that followed, the U.S. capitalist class was emboldened by the super-profits they made in the post-war era and embarked on a witch hunt designed specifically to crush any sympathy for socialist and communist politics of any sort.

This was the now infamous Second Red Scare, also called the McCarthy period after right-wing Senator Joseph McCarthy. Through national and state laws as well as through pressure on union officials, they blacklisted and drove out of the unions many militants who had helped the working class organize itself so effectively in the 1930s and 1940s.

Union officials now began to be more concerned about protecting their jobs in their roles as mediators and thus unwilling to lead struggles against the bosses. Class struggle receded, and revolutionaries were pushed out. These business-as-usual union officials were unwilling to struggle against the power of the corporations and the state and therefore accepted what was proposed to them by the corporate bosses. A new round of attacks in the ‘70s and ‘80s ushered in another period of concessions and defeats.

Today when we read the history of the Hormel strike, we honor those 1,500 Hormel workers. They were willing to fight for over a year against a powerful corporation, the government forces allied with it, and their national union officials. The actions taken by the Austin workers, and by other workers who supported them, are examples of how ordinary people can organize and accomplish extraordinary things. Their fight showed determination, imagination, organization, efficiency and courage.

For a moving overview of the strike that includes the efforts of UFCW leadership to undermine the workers as well as the personal stories of some of the striking workers, the heart-wrenching documentary American Dream, by notable documentarian Barbara Kopple, is an excellent source. This useful article, https://againstthecurrent.org/atc002/behind-the-hormel-strike-fifty-years-of-p-9/ provides more detail on Austin and Local P-9 both before and during the strike.