Over two million people have been forced to flee South Sudan, a country of 12.4 million people. This is now the third- or fourth-largest refugee crisis in the world, after Syria, Afghanistan, and most recently Ukraine. This exodus is a result of economic collapse and decades of civil war, which have created extreme poverty and ongoing famine, with over a million children in South Sudan suffering from malnutrition. The months of May to July are known as the “lean season” – the period between harvests in which many Sudanese people will face shortages. This year’s lean season is compounded with the economic crises of civil war and a global pandemic, and will consequently be even more disastrous: over 8 million people will experience food insecurity, and “2 million people, including 1.3 million children under the age of 5, and 676,000 pregnant and lactating women, are expected to be acutely malnourished.” North Sudan (usually named simply Sudan) is not spared from this crisis. In the western region of Darfur and the northeast, about 7 million people face severe food insecurity.

The causes of this humanitarian crisis in both North and South Sudan are similar to those behind the other major famines in the world right now. They are legacies of colonialism and capitalism. The modern capitalist system expanded globally through the exploitation of poorer nations by the industrial powers. The biggest industrial power in the world now and for a long time is the United States – home to the world’s richest and most powerful capitalists. And they have had a hand in devastating Sudan. The crisis in Sudan offers another example of how capitalism works and its horrific human cost.

The area now known as Sudan was ruled by various kingdoms such as Kush and Nubia in the region of ancient Egypt. Its northern regions were under the control of the ruling dynasties of Egypt throughout much of antiquity. Northern Sudan underwent a slow conversion to Islam and adoption of the Arabic language between the 8th and 16th centuries. In fact, the name “Sudan” comes from “Bilad-al-sudan,” which means “country of the Blacks” in Arabic. In the 19th century, Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire, but underwent rapid economic development and became effectively an independent state. The rulers of Egypt wanted Sudan’s natural resources and began to extend their control to the south, taking over Sudan.

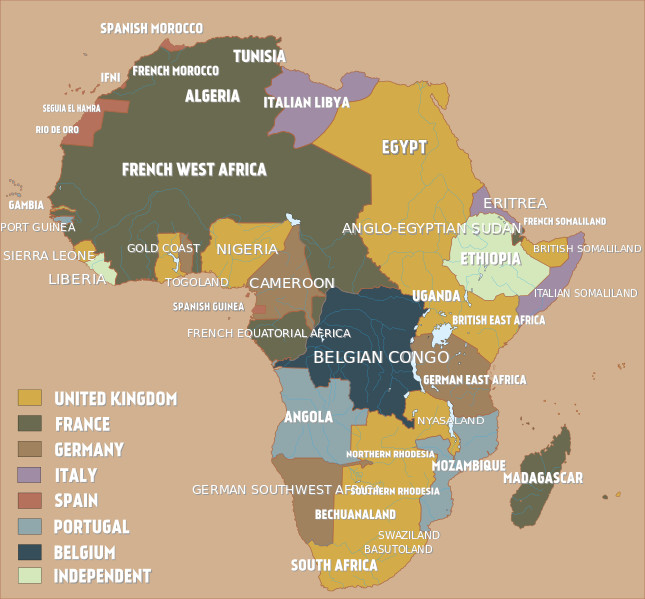

The late 19th century saw the “Scramble for Africa,” in which the capitalists of western Europe carved up Africa in their interests. European rulers murdered millions of indigenous Africans so that their corporations could plunder the continent. The British capitalists then competed with Egyptian claims over the territory of Sudan. This conflict was resolved with a shared-control agreement in 1898, in which Britain jointly ruled Sudan with Egypt. However, Egypt’s influence in the region declined and the British became the effective rulers of Sudan by the 1920s.

Northern Sudan was predominantly Muslim and Arabic-speaking, while the south remained a patchwork of many cultures and languages. The British made the division between North and South official, and enforced a strict border between them. The south was subjected to a brutal “closed door” ordinance, which meant putting the region under economic blockade. Northern Sudanese people were not even allowed into the south, blocking all trade and preventing economic development of the south. The British used their expertise in divide-and-conquer tactics of exercising colonial power –handing power to corrupt and violent rulers of their choosing to promote strife and oppression between different groups. The main source of profit was cotton, which was managed through the British-based Sudan Plantations Syndicate. British interests in Sudan’s cotton declined in the 1930s due to the Great Depression, which dealt a severe blow to the economy of Sudan.

Racism and colorism in Sudan have strong roots in centuries of slave trade. Sudan became one of the most active slave-trading regions in Africa in the 19th century. In the first half of the 20th century, the complete isolation of South Sudan imposed by the British further intensified racial animosity between north and south: the northerners of Sudan, who are usually lighter-skinned, identify as Arab (as opposed to African) and color designations such as “green” and “blue-black” are used to divide people by the shade of their skin. Northern Sudanese people have higher representation in positions of privilege and power, and tend to look down on the so-called “Blacks” of South Sudan. This kind of racism has figured heavily in the decades of Civil War and genocide in Sudan.

The animosity between north and south erupted violently in late 1955, just as Sudan was to declare its independence from British and Egyptian rule. The elites of the south found themselves at the mercy of the northern government, and southern army officers mutinied in response. This sparked the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972), for which weapons were supplied first by the British (until 1967), then the Soviet Union (up to 1971), and then the United States, the world’s biggest arms exporter.

The first civil war ended with an agreement granting the south some political sovereignty, but it wasn’t long before the Second Sudanese Civil War erupted in 1985 between the northern government and the insurgents of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) in the south. This time, the conflict was also fueled by contested oil reserves (discovered in the 1970s and 80s) along the north-south border, which the northern elites wanted to control. The war was horrific. It killed two million people and displaced four million. The Second Civil War ended in 2005 with the recognition of South Sudan, which officially became an independent republic in 2011.

With the official border drawn between North and South Sudan, the oil reserves are in the South, while the oil refineries and pipelines are in the North. As a result, both sides suffer economically. The North lost its direct access to the oil, while the South completely depends on the North to export it to other countries. In addition, increasing amounts of oil revenue are used to pay of South Sudan’s considerable debt, which the southern elites repeatedly resort to as a short-term solution to government deficits. Before the war, U.S., French and Canadian oil companies profited from Sudan’s oil. The Sudanese government violently displaced many people, exploiting divisions between rival groups and encouraging them to raid and enslave each other in order to clear the way for Western oil companies to operate freely. The civil war scared off the western oil companies, however, and today almost two-thirds of Sudan’s oil goes to China, which controls much of the oil infrastructure.

Petroleum industry waste contains many toxic chemicals such as sulfur, lead, and hydrogen sulfide, which seep into the ground and contaminate water and soil. In a system dominated by international capitalists, the profit motive trumps any considerations of environmental or human health. And in poor developing countries like Sudan with fewer environmental regulations, this corporate neglect is completely out of control. As a result, Sudan’s oil industry causes environmental devastation, droughts, and poisoned water, due to the slipshod disposal of industrial waste and the construction of oil sites on farmlands.

Although the Second Civil War ended in 2005, war was not over in Sudan. In 2003, towards the end of the Second Civil War, the government of the north (based in Khartoum and composed of Arab elites) clamped down on insurgents from the western region of Darfur. The insurgents opposed the central government and their attempt to dominate the non-Arab Darfuri people. This expanded into a genocide of hundreds of thousands of Darfuris committed by Sudanese troops and affiliated paramilitary groups. This extended civil war in Darfur continues in spasms, although a ceasefire was declared in 2010.

To make matters worse, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), the political wing of the SPLA that fought against North Sudan in the Second Sudanese Civil War, itself broke into two factions — the SPLM and SPLM-IO (SPLM-In-Opposition) — competing for power in South Sudan. Tensions between the opposing factions exploded into a civil war in 2013, which lasted until 2020. The war killed 380,000 people and displaced over three million. The United States under the Bush Administration supplied arms to the SPLM, and Obama continued this policy by facilitating more arms shipments via Uganda (a U.S.-ally in the region). The weapons originated from various countries, including the United States, China, and Israel.

In North Sudan in 2019, the military took power in a coup and ousted President Al-Bashir. When people protested in the capital Khartoum, the Sudanese military and paramilitary forces fired on the protesters, killing more than 100 people. The high command ceded to a semi-military government later that year, but the head of the armed forces led another military coup in 2021 that dissolved the joint government and transferred all power to the military once again. This junta still rules North Sudan, and still shoots protesters. Nevertheless, protests have continued against the junta and deteriorating living conditions.

In recent years, the effects of climate change have been felt more painfully throughout Sudan, with increased desertification and drought, which intensifies food insecurity. Centuries of slavery, decades of civil war, the imposed border between North Sudan and South Sudan, the imperialist contest over oil, and the extreme economic underdevelopment of the South going back to British colonialism – all these have made Sudan one of the poorest and most devastated places on Earth. The coming months will see disastrous famine in South Sudan, which like the famines in Ethiopia, Nigeria, Yemen, and Guatemala, is the result of colonialism and is kept going by global capitalism.

The famine in Sudan is not usually represented, let alone explained, in the corporate media. In general, Africa doesn’t command much attention from the mass media in the United States – a glaring expression of institutional racism. As the media neglects the poor and working people of the world, we must bring awareness about the famine in Sudan and other war-torn countries. War over resources, racism, climate change and drought, massive poisoning of water by petrochemical companies – these are all crises that afflict Sudan to an extreme degree. But they also exist throughout the world, including to varying degrees in the United States today. As capitalism continues to promote war, environmental destruction, famine, and other horrors, no one in the world will be spared from the disastrous consequences of this system.