An investigation by the Department of the Interior revealed that the remains of over 500 children were discovered in 53 mass burial sites in Indian boarding schools across the United States. Many historians argue that the number of deaths is likely much higher.

The 106-page report goes into great detail about how settler colonialism led to the ethnic cleansing of indigenous people, whether through attempts at violent extermination or assimilation by consciously destroying the indigenous way of life. In reality, the role of the Indian boarding schools represented a hybrid of both.

This philosophy was famously summed up in the quote, “kill the Indian, save the man”, from a speech by the American military leader R.H. Pratt, who fought in the “Indian Wars” of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Fittingly, Pratt was a founder of the Carlyle Boarding School in Pennsylvania, which became a model for other boarding schools.

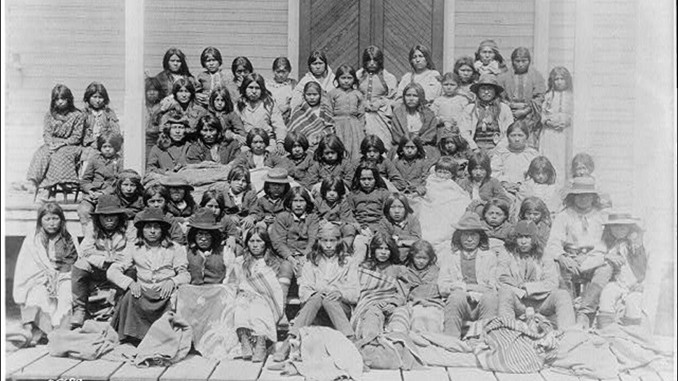

From 1819 to 1969, 408 Indian boarding schools were run directly by the U.S. government or by Catholic or Protestant churches with federal funding. The boarding schools were heavily concentrated in Oklahoma, Arizona, and New Mexico. Tens of thousands of indigenous youth were taken against their will from their communities and forced to live in these so-called “schools.”

When the young people came to the boarding schools, everything was done to strip them of their indigenous cultural identity. Their hair was cut off, their personal traditional belongings were confiscated and they were punished for speaking their own languages. This forced transfer of children from one group to another is one of the definitions of genocide recognized as a crime by the United Nations.

The boarding schools did not resemble “schools” in the traditional sense. They were less engaged in teaching subjects like literacy and mathematics, and more concerned with teaching obedience, military discipline, U.S. patriotism, and religious worship. The boarding schools also used the forced labor of the children in agriculture, brick-making, garment-making, and other work.

Violence against the children was commonplace. Because of this, many never made it home from the boarding schools. They were subjected to solitary confinement, flogging, withholding of food, whipping, slapping, and cuffing. Sometimes older children were coerced to punish younger children. This violence and abuse directed toward the children led to the untold amounts of suffering and death that this report is bringing to light.

Boarding schools also served another purpose. They proliferated at a time when the United States government was encouraging white settlers to move westward and take hundreds of millions of acres of land, displacing indigenous peoples. The boarding schools were used as a tool in that process. Former commissioner of Indian Affairs, Ezra Hayt, said explicitly that “the children would be hostages for the good behavior of their people.”

While they have buried the bodies of the children who suffered the worst abuse in the boarding schools, their history has not been buried. The stories of these children have come to light, been acknowledged, and the experiences of the many who suffered and lived are now being validated. The legacy of this history is still with us today, throughout the U.S., where the children of these abused parents have felt the profound consequences.

Not only does understanding the past inform us about how we got to our present situation but the better we understand the world we live in, the better equipped we are to resist and move forward to build a genuinely liberated world in which all peoples are respected and able to determine their own fates.