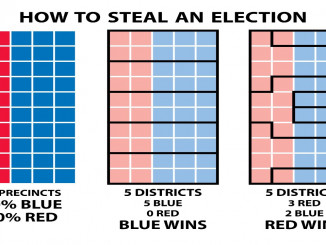

On June 26th, 1894, members of the American Railway Union began a boycott in support of striking workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company in Pullman, Illinois (today part of Chicago’s South Side). This boycott meant workers all across the railway industry refused to work on any train that had a Pullman car attached to it in order to support the Pullman workers on strike. In effect, this decision expanded what began as a local strike against Pullman into a nationwide strike against the entire railway industry. In fact, it was the largest strike in U.S. history at the time and brought a large section of the American working class into direct conflict with their economic and political oppressors — it was out and out class warfare. Although the strike was ultimately defeated, it was a clear demonstration of the revolutionary potential of the working class when it is engaged in struggles on this scale. The militancy, the organizing, and the solidarity shown by the railroad workers not only demonstrated the potential for the working class to organize and fight for themselves, but it also pointed towards the power workers have to stand up to the whole capitalist class and completely transform society.

The Context

Employing hundreds of thousands nationwide, with the highest density of railroads and workers in the Northeast and Midwest, by 1890 the railroad companies were among the largest and most powerful corporations in the United States. They dominated state and national politicians, bribed and bullied officials and small towns, charged extortionate prices to farmers, and, of course, exploited their own workers in a variety of ways. The company owners were emblematic of the “nouveau riche” (the “new rich”) capitalist class that had developed in the late 19th century, and they used their economic power to dominate politics and society.

While rail workers from the 1870s on had fought for themselves and challenged the railroad magnates, the most famous and cautionary example of this remained the massive Great Strike of 1877, in which hundreds of thousands of workers struck against wage cuts and other abuses by the Baltimore and Ohio (B+O) Railroad. This massive upheaval was repressed by state militias and federal troops who forced workers back to work at gunpoint, killing 100 along the way. But that strike had been disorganized with no true central leadership in any way to guide the upsurge.

In the years that followed, rail workers formed Railway Brotherhoods, organizations that combined mutual aid with bureaucratic negotiations over work rules and basic wages. But they held no real power, and in fact weren’t even members of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the rapidly growing but quite conservative craft union organization led by Samuel Gompers. By the early 1890s, it was clear to the mass of railway workers that these various brotherhoods alone were not very useful in order to fightback against their worsening conditions and that something more was needed.

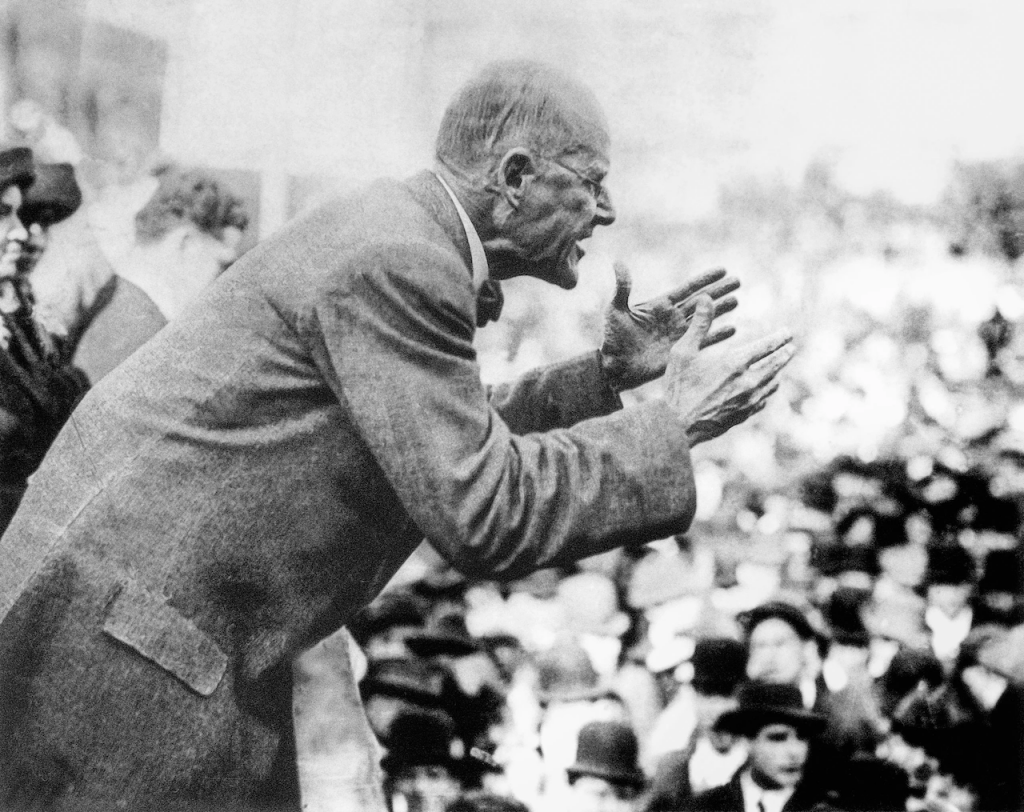

It was in this context that representatives of some rail workers brotherhoods came together in February 1893 to form the American Railway Union, or ARU. This union was a federation of dozens of brotherhoods into a new type of union — an industrial union — representing workers not by specific craft, but by virtue of their employment in a specific industry. Its driving force and new president was a young railroad worker, union leader from Indiana, Eugene Victor Debs.

The ARU’s first major action was in August in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where it led workers on an 18-day strike against wage cuts for workers on the Great Northern Railway. While they didn’t win better wages or new benefits, the strike forced the railway company owners to reinstate the wage cuts. This was a small but significant victory. As in most cases, when workers in a union win a strike or make significant gains, other workers flock to the union with a sense of optimism that they, too, can be a part of improving their conditions through solidarity with their fellow workers. By the end of the year the recently fledgling ARU had 150,000 members, nearly as many as the entire AFL.

The Strike at Pullman

The Pullman Palace Car Company, owned by George Pullman, ran a model “company town” — it was based in Pullman Illinois, named after the company, which owned the entire town. Pullman had practically complete control of the workforce, all stores, prices, and rents — all of which put workers in a tight spot even in good times. But when a depression hit the U.S. in 1893, Pullman cut wages by an average of 33% in the winter and spring of 1894, yet prices and rents remained the same.

In response, in March and April the majority of Pullman’s workers joined the ARU. In the first days of May the workers sent a committee to meet with Pullman to ask him to either reinstate the previous wages or cut prices and rents. Instead, Pullman promptly fired three members of the committee, infuriating the workers. While top ARU leaders, including Debs, urged caution, the Pullman workers voted to strike, and on May 11, the Pullman Strike began.

The localized strike of only a few thousand workers of one union local against a powerful employer was a desperate uphill battle from the start. After a month, workers and their families were on the verge of homelessness and starvation. Their situation was dire.

The Strike Expands

But at the first national ARU convention in mid-June, delegates voiced strong support for the Pullman workers, and urged a boycott (or “sympathy strike”) by all ARU members in support of the local strikers. While Debs and other ARU leaders were still not in favor of throwing the weight of the entire union behind the strike, when Pullman refused to negotiate any further, ARU delegates voted on June 25th to initiate a boycott by all ARU members against all Pullman rail cars. Since Pullman cars were used on the majority of passenger trains throughout the U.S., this was in effect a call for a nationwide rail strike.

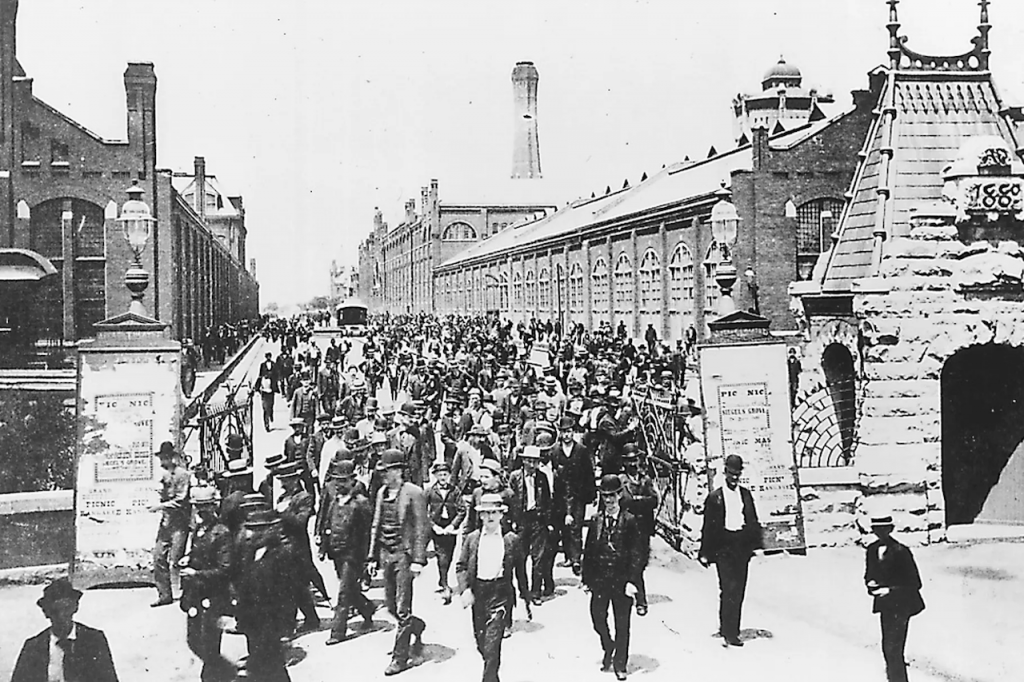

On June 26th, the real strike began. Within a few days, not only were the 150,000 ARU members not working, but another 110,000 railway workers who were not yet members of the ARU had joined the strike in an inspiring show of solidarity. Debs and the leadership in Chicago, despite wanting to avoid the boycott, threw their full energy into the strike, running a strike headquarters, coordinating communication, and giving instructions. But the real work of the strike depended on the workers in hundreds of smaller locations who were responsible for local actions and organizing their local workers, leading to many smaller boycotts and strikes springing up without any direction from ARU leaders. The majority of train lines in the Midwest ceased to function, and rail transport nationwide was slowed if not stopped. Adding to the sense of momentum, many non-railroad workers in Chicago and other cities also wanted to participate in a general strike, in which all workers would strike in support of the Pullman workers and ARU. This was all made possible by the call for the boycott, and is the reason why June 26th became such a turning point in the strike.

Railroad workers were showing their solidarity with each other and their potential power to disrupt if not halt the entire American economic system. The New York Times, in a statement that makes clear the threat that the strike posed for the capitalist class, called it “the greatest battle between labor and capital that has ever been inaugurated in the United States.” After one week it seemed that the workers had the upper hand, and would win this battle against their oppressors.

The Strike Confronts the State

The capitalist class, however, was even better organized than the workers, and they used their wealth and power to bring the government into action on their behalf. As the ARU had been organizing, so had the railroad companies, who created the GMA, or General Managers Association, to coordinate their fight against their workers. The GMA swung into action, planning strategy, hiring strikebreakers, and generally using the money and power of the industry to turn public opinion against the workers and to influence politicians who were already sympathetic to the companies. The GMA pushed President Grover Cleveland and his Attorney-General Richard Olney (who had worked as a railroad company lawyer for 35 years before becoming Attorney-General) to get injunctions against the workers and to use federal troops to force workers back to work (an injunction is basically a threat by the courts of massive fines and jail time if the workers didn’t cooperate). Their goal was not just to end this strike, but to completely destroy the ARU, which they viewed as a potential leader of the larger working class.

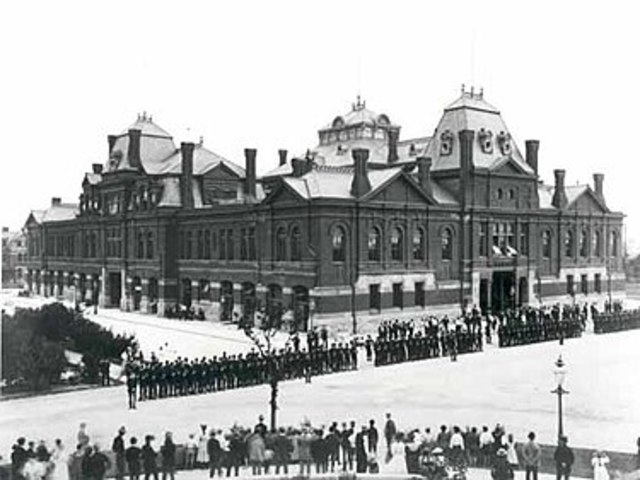

From July 2nd on, the tide turned. Injunctions were issued, new federal attorneys were appointed in Chicago, and nearly 14,000 federal troops occupied the massive city, along with thousands of others nationwide who occupied portions of smaller cities and towns to force workers back to work. By the time the strike ended, federal or state troops had been called out in Nebraska, Iowa, Colorado, Oklahoma, California, and Illinois, and an estimated 34 people had been killed in the clashes. The final blow came on July 10, when the ARU offices were occupied and ransacked, and Debs and other ARU leaders arrested.

But aside from the capitalists and their allies in the government, another group also helped undermine the strike. Many leaders of the conservative Railway Brotherhoods refused to strike, and encouraged their members to continue working as usual. Samuel Gompers and the AFL also refused to throw their support behind the strike. For these conservative trade unionists, a radical strike was the last thing they wanted, and they viewed it as a dangerous threat to the tiny privileges they had slowly won — hence the unwillingness of their leadership to show solidarity with other workers.

Lessons of the Pullman Strike

While the Pullman Strike ended in defeat, as did most strikes of the late 19th century, it has a significance that overshadows its defeat and offers a number of lessons for workers in the years following as well as today.

Although the ARU was destroyed by the government, it was the first significant attempt to form an industrial union, which would only later emerge as a powerful model of unionism in the 1930s, during the forceful and successful strikes in Toledo, Minneapolis and San Francisco in 1934, and the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936. This model of unionism offered workers a way of organizing themselves that allowed them to unite on a far larger scale than ever before, and to stand up to the most powerful forces in society more directly and effectively. It also showed the tremendous sense of solidarity that workers are capable of, even if they do not work in the same industry. It was and is that “spirit” of solidarity within the working class, as one participant wrote, that continues to provide a basis for workers to unite their struggles into a common fight, and enormously increase their power.

The Pullman Strike also demonstrated once again to workers that the government is not a neutral force in society. The government was (and still is) an instrument of class domination, which is used by the capitalist class to regulate or manage class conflict whenever possible, and to stifle class conflict through legal mechanisms and force if necessary.

Debs, other ARU leaders, and even many rank and file railway workers had framed their original objectives in a language of patriotism and the brotherhood of man, and had not intended to lead a nationwide strike. They simply wanted dignity, respect, and the ability to provide for their families even in times of depression. But these very basic demands were far too much for the business owners or the government to allow. And once these demands were backed up by hundreds of thousands of workers ready to fight, in the eyes of the capitalist class and their government, they had no choice but to try to crush these workers and their organizations — because it could threaten the very foundation of capitalist society. The armed forces of the U.S. government were the deciding force in the strike, and as organized and determined as these workers were, they were not yet prepared to take it on. To do that, a very different and much broader, revolutionary organization must be constructed.

Perhaps the most interesting postscript to the Pullman Strike was the path taken by its chief protagonist in the coming decades. Despite beginning his work for the railroads as a patriotic, pro-business worker and even unionist in his early years, Eugene Debs slowly became more radical under the course of events. While this process was well underway before the Pullman Strike, it was only after the strike that it reached fruition. While spending nearly a year in prison for his role in the strike, Debs was able to further develop his study of revolutionary socialist ideas, reading Karl Marx’s Capital, as well as the works of other socialist militants, and became a convinced socialist. The strike had demonstrated clearly for him how the workers were exploited and oppressed by the capitalist class and the capitalist government, and that within a capitalist system the workers would never get a fair shake, much less have real democracy. In 1898, he was a founding member of the Social Democratic Party of America (SDP), later to become the Socialist Party of America, and remained the primary American voice for socialist politics from then until his death in 1926. The path of Debs, from working class activist to revolutionary socialist militant, should be a model to all workers who want to see a better life for working people. He realized that as long as we live within a capitalist society, the opportunities for workers to live decent and fulfilling lives will always be constrained by the needs of the capitalists, who put profit over people at all times.

For all these reasons, the Pullman Strike is one of the most significant workers upsurges in American history. It teaches us lessons about the power and potential of workers when they organize on a large scale and show solidarity with one another. It exposes the indisputable class nature of the government and whose interests they protect. And it also highlights the limitations of traditional unions within a capitalist system, and reminds us that in order for workers to ever truly win the world that we want, the entire capitalist system must be replaced, and to do that we must build revolutionary organizations of the working class.