download a PDF of this pamphlet

This is the story of the 1946 Oakland General Strike told by a participant – Stan Weir, a seaman at the Oakland Port, and a revolutionary working class militant. We reprint this pamphlet because it shows first-hand the power of the working class. Workers today need to begin to organize to exert their power, just as the workers in 1946 did. We need to turn our anger into action by organizing where we are – in our communities and workplaces. In fact we must go further. This system serves only the wealthy. We need to fight for a worker-run society that meets the needs of those who produce all the wealth. We need to fight for socialism.

– Speak Out Now

_________________________________________________

An account of the General Strike in Oakland, California (1946) by Stan Weir

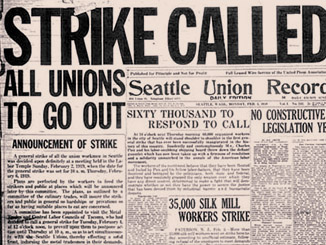

The Oakland (California) General Strike was an extension of the national strike wave. It was not a ‘called’ strike. Shortly before 5 a.m., Monday, December 3, 1946, the hundreds of workers passing through downtown Oakland on their way to work became witness to the police herding a fleet of scab trucks through the downtown area. The trucks contained commodities to fill the shelves of two major department stores whose clerks (mostly women) had long been on strike. The witnesses, that is, truck drivers, bus and streetcar operators and passengers, got off their vehicles and did not return. The city filled with workers, they milled about in the city’s core for several hours and then organized themselves.

By nightfall the strikers had instructed all stores except pharmacies and food markets to shut down. Bars were allowed to stay open, but they could serve only beer and had to put their jukeboxes out on the sidewalk to play at full volume and no charge. “Pistol Packin’ Mama, Lay That Pistol Down”, the number one hit, echoed off all the buildings. That first 24-hour period of the 54-hour strike had a carnival spirit. A mass of couples danced in the streets. The participants were making history, knew it, and were having fun. By Tuesday morning they had cordoned off the central city and were directing traffic. Anyone could leave, but only those with passports (union cards) could get in. The comment made by a prominent national network newscaster, that “Oakland is a ghost town tonight,” was a contribution to ignorance. Never before or since had Oakland been so alive and happy for the majority of the population. It was a town of law and order. In that city of over a quarter million, strangers passed each other on the street and did not have fear, but the opposite.

Before the second day of the strike was half over a large group of war veterans among the strikers formed their own squads and went through close-order drills. They then marched on the Tribune Tower, offices of the anti-labor Oakland Tribune, and from there marched on City Hall demanding the resignation of the mayor and city council. Sailors’ Union of the Pacific (SUP) crews walked off the three ships at the Oakland Army base loaded with military supplies for troops in Japan. By that night the strikers closed some grocery stores in order to conserve dwindling food supplies. In all general strikes the participants are very soon forced by the very nature of events to themselves run the society they have just stopped. The process in the Oakland experiment was beginning to deepen. There was as yet little evidence of official union leadership in the streets. The top local Teamster officials, except one, were not to be found; the exception would be fired five months later for his strike activity. International Teamster President Dave Beck wired orders “to break the strike” because it was a revolutionary attempt “to overthrow the government.” He ordered all Teamsters who had left their jobs to return to work. (Oakland Tribune, December 5, 1946)

A number of the secondary Oakland and Alameda County union leaders did what they could to create a semblance of straight trade-union organization. The ranks, unused to leading themselves and having no precedent for this sort of strike in their own experience, wanted the well-known labor leaders in the Bay Area to step forward with expertise, aid, and public legitimization. The man who was always billed as leader of the 1934 San Francisco General Strike, ILWU President Harry Bridges, who was then also State CIO President, refused to become involved, just as he did 18 years later during the Berkeley Free Speech Movement struggles. The rank-and-file longshoremen and warehousemen who had been drawn to the street strike were out there on their own. No organized contingents from the hundreds available in the warehouse and longshore hiring halls were sent to help, no CIO shops were given the nod to walk out or “sick-out”. Only through CIO participation could significant numbers of blacks have been drawn into this mainly white strike. The ILWU and other CIO unions would honor picket lines like those around the Tribune Tower or at the Oakland Army Base, but otherwise they minded their own business. Bridges had recently committed himself to a nine-year extension of the wartime no-strike pledge.

The one major leader of the San Francisco General Strike who would come to Oakland was the SUP’s Secretary Treasurer, Harry Lundeberg. On the second night of the strike he was the principal speaker at the mass meeting in the overflowing Oakland Auditorium. He had been alerted when the strike was less than three hours old via a call from an old-time member at a pay phone on an Oakland street. By noon there were contingents composed mainly of Hawaiians acting as “flying squads”, patrolling to find any evidence of strike-breaking activity. They enlarged upon their number by issuing large white buttons to all seamen or persons on the street that they knew. The buttons contained the words “Brotherhood of the Sea”. They represented the first officially-organized activity on the street. They did not attempt to run the entire strike or take over. It takes time for seamen to get over the idea that they are somehow outsiders. The feeling is all the stronger among Hawaiian seamen ashore or residing in the States. They limited their activity to trouble-shooting. They won gratitude and respect. When Lundeberg spoke at the meeting, he had no program of action beyond that of the Oakland AFL leaders. But he got a wild response. He did not approach the microphone reluctantly. His demeanor reflected no hesitancy. Unlike the other speakers, he bellowed with outrage against the city council on behalf of the strikers. In a heavy Norwegian accent he accused: “These finky gazoonies who call themselves city fathers have been taking lessons from Hitler and Stalin. They don’t believe in the kind of unions that are free to strike.” All true, but whether he knew it or not, by focusing on the city council and no more, he was contributing to the undercutting of the strike. Instead of dealing with the anti-labor employers and city officials through the medium of the strike, plans were already being formulated to deal with the crisis in the post-strike period by attacking the City Council through use of the ballot box. The top Alameda County CIO officials were making hourly statements for the record that they could later use to cover up their disloyalty. The AFL officials couldn’t get them to come near the strike, but they could be expected to participate in post-strike electoral action.

The strike ended 54 hours old at 11 a.m. on December 5. The people on the street learned of the decision from a sound truck put on the street by the AFL Central Labor Council. It was the officials’ first really decisive act of leadership. They had consulted among themselves and decided to end the strike on the basis of the Oakland City Manager’s promise that police would not again be used to bring in scabs. No concessions were gained for the women retail clerks at Kahn’s and Hastings Department Stores whose strikes had triggered the General Strike; they were left free to negotiate any settlement they could get on their own. Those women and many other strikers heard the sound truck’s message with the form of anger that was close to heartbreak. Numbers of truckers and other workers continued to picket with the women, yelling protests at the truck and appealing to all who could hear that they should stay out. But all strikers other than the clerks had been ordered back to work and no longer had any protection against the disciplinary actions that might be brought against them for strike-caused absences. By noon only a few score of workers were left, wandering disconsolately around the now-barren city. The CIO mass meeting that had been called for that night to discuss strike “unity” was never held.

In the strike’s aftermath every incumbent official in the major Oakland Teamsters Local 70 was voted out of office. A United AFL-CIO Political Action Committee was formed to run candidates in the race for the five open seats on the nine-person City Council. Four of them won; the ballot listed the names of the first four labor challengers on top of each of the incumbents, but reversed the order for the fifth open office. It was felt that the loss was due to this trick and anti-Semitism. The fifth labor candidate’s name was Ben Goldfarb. Labor’s city councilmen were regularly outvoted by the five incumbents; however, the four winners were by no means outspoken champions of labor. They did not utilize their offices as a tribune for a progressive labor-civic program. They served out their time routinely, and the strike faded to become the nation’s major unknown general strike.

The Oakland General Strike was related to the 1946 strike wave in time and spirit, and revealed an aspect of the temper of the nation’s industrial-working-class mood at war’s end. Labor historians of the immediate post-war period have failed to examine the Oakland Strike, and thus have failed to consider a major event of the period and what it reveals about the mood of that time. In developing their analyses they have focused almost entirely on the economic demands made by the unions that participated in the strike wave. These demands were not unimportant. But economic oppression was not the primary wound that had been experienced daily during the war years.

The “spontaneous” Oakland General Strike was a massive event in a major urban area with a population similar to that of all major World War II defense-industry centers. Thousands had come to the Bay Area from all corners of the nation – rural and urban – in the early war years, and had stayed. Every theatre of war was represented among armed-forces veterans returning to or settling in this largest of Northern California’s central city cores. The Oakland General Strike revealed fundamental characteristics of a national and not simply a regional mood. Its events combined to make a statement of working-class awareness that World War II had not been fought for democracy. Or, more pointedly, it was a retaliation for the absence of democracy that the people in industry and the armed forces had experienced while “fighting to save democracy in a war to end all wars.” The focus of people’s lives was still on the war. They hadn’t fought what they believed to be “a war against fascism” to return home and have their strikes broken and unions housebroken.

Emotionally, their war experiences were still very real, and yet they were just far enough away from those experiences to begin playbacks of memory tapes. The post-war period had not yet achieved an experiential identity. The Oakland Key System bus drivers, streetcar conductors, and motormen who played a leading role in the strike wore their Eisenhower jackets as work uniforms, but the overseas bars were still on their sleeves. Like most, they had lost four years of their youth; and while they would never complain about that loss in those terms, there were other related grievances over which resentment could be expressed.

* Interview abridged for space. Account and full interview available at: www.flyingpicket.org

An Interview with Stan Weir, 1990

Stan Weir: […] The General Strike was part of the ’46 strike wave. You can’t extract one from the other. There was a great deal of dammed up militancy. People who worked throughout the War had been taking all this crap from employers in the name of the War effort, that kind of phony patriotism, instead of real patriotism. It was time to catch up after the War, so there were wildcat strikes going on apace. As a matter of fact, there were more people out on strike in 1946 in the ’46 strike wave than any time before or since. It is the largest strike wave that ever occurred in the United States. That occurred as a last gasp of a labor force that was coming back, of a labor force that was still in place. That is, the G.I.’s were not all back yet, and the people who had spent this last four years together were still pretty much together, or they hadn’t been swamped by new workers coming in or guys returning from the Armed Forces. A lot of new technology and new mechanization had not yet been introduced.

The Oakland General Strike was, I think, in December. Mary got in my jeep and drove down with some of her girlfriends from campus to travel around the streets and look at it.

We in the CIO were not a part of it officially. That is, the State of California CIO was run by Percy Peers. They were for having the General Strike after the War – having a no-strike pledge almost permanently for nine years after the War. When the General Strike broke out, the three ships at the Oakland Army Base, the gangs all walked off ‘em and went out in the streets and went on strike. Bridges immediately sent gangs of politicals back to those ships and kept working. In order to participate in that general strike, we had to stay out of work, be on absenteeism.

Pat McAuley: The Maritime workers were a big part of this, weren’t they?

Weir: Well, they were, partly because I found them. That is, I was still a member of the Sailors’ Union. I am downtown, in Oakland. I got off the streetcar. The strike had started. There was no bus to take me the rest of the way to East Oakland to my job.

I didn’t see any official leadership. There was not an official leader anywhere to be found. They’re all hiding. This is strictly rank and file. Downtown alone went on strike alone.

So, I (and it might not have been the best thing to do) phoned up the Sailors’ Union, got Lundeberg, and said, “Hey, there’s a strike over here and there’s no organization. We need a way of developing a network. Whatever you can do.” What he did was he sent about thirty Hawaiians with a bunch of SIU-SUP Brotherhood of the Sea buttons and (they) began distributing those as some kind of strike police badge.

At the Oakland General Strike meeting downtown in the Oakland Auditorium, Lundeberg was the only one to know what to say. It was all demagogy – “the Oakland City Council had tried to break the strike.” Going on that “the General Strike had taken lessons from Hitler and Stalin, and they were finks.” Anyway, he was the only one who talked radical like that, ‘cause he knew from the past, the recent past, although he had already sold out. I hadn’t yet absorbed that sellout, and that’s why I would call the union, get him, and tell him to get some forces over there.

McAuley: Did the strike die because of lack of strong leadership?

Weir: Yes. The leadership of the retail clerks and that of the Teamsters was very different. That is, finally the retail clerks’ leadership did show up. But they had all this strength. Remember, the General Strike was called in support of the workers at Kahn’s and Hastings department stores. Here, they had the town shut down. That leadership did not come up with an agreement that would protect the jobs of those people and settle their grievances. They went back to work with no protection and with no gains.

McAuley: But a lot of other workers were so ready to strike.

Weir: Yes!

McAuley: That they walked out in support of these retail clerks.

Weir: Yes. Absolutely. That accidental strike, the so-called accidental strike, without any leadership, with no one calling it, turned out to be an opportunity for people to vent their feelings about what had happened to them on the job during the War.

The leaders, the real leaders of that strike, were the Key system bus drivers, who were just back from after the War. They were still wearing the Eisenhower jackets, but now they had converted them to bus driver jackets. A lot of them still had their gold hatch marks, overseas marks, on their jackets. I remember, and I’ve told this a number of times, an Army recruiting truck came down the street during the General Strike.

Some young lieutenant in back of the truck says into the microphone over the loud P.A. system: “You ought to be ashamed of yourselves striking. You ought to be out fighting for your country.” It was so recently after the War, maybe he thought he could get away with that.

Some big guy said, “Where do you think we got these?” and pointed to his overseas marks. He said, “Fall in!” and about 50 to 75 guys fell in, in close order, and he started them in a close order drill, and more guys, and more guys. Pretty soon, we had a company, not a platoon but a company. Pretty soon, he had more than a company. I mean he had hundreds, in close order drill. What are you going to do with them now?

Marched on City Hall. Demanded to see the head of the City Council. No one would come out to talk to them. But they went to the seat of power in the city, the ones who had called on scab trucks from L.A. to come and be herded into those stores by Oakland police.

McAuley: [...] Is there anything else about that General Strike that comes to your mind?

Weir: The General Strike confirmed for me ideas that I had been having for some time. It seemed to me that wherever I looked, the membership of unions, and of political parties I belonged to, a political grouping I belonged to, the membership was ahead of the leadership. But I’m going to talk about unions now.

It seemed to me not only were the members of the unions I had been in, and was in, ahead of the official line on how to fight the employer and willingness to fight the employer, way ahead. They were way ahead when it came to the invention of democratic methods for furthering that fight. Those methods developed a societal set of attitudes on the part of these people.

The officialdom you mentioned, when I said that you couldn’t find a union official in downtown Oakland, and you asked me before we started here today, “Do you think that shocked the officials?” Well, it had to have shocked them half out of their senses. At that time, it was close after the War.

I, for example, at Cedar and San Pablo, got a bus to Ashby, got a trolley in downtown Oakland, then got a bus to East Oakland, where I was working in the East Oakland Chevrolet plant. When we got to downtown Oakland that morning, we rolled in somewhere between 6 and 7:30. A man came running over to our streetcar and talked briefly, just briefly, and fast, and hard, to our conductor and motorman on the streetcar. They got off and began to walk away. We yelled at them, “Hey! What’s this?!” He explained that Los Angeles scab-driven trucks with merchandise for the two department stores that were on strike, Kahn’s and Hastings department stores, that these trucks were being herded through the city, right now, by the Oakland police, and that’s why. And they disappeared.

So, we were all there downtown. We couldn’t get to work. Immediately, a carnival kind of attitude hit us.

McAuley: Did they think the trolley-

Weir: Right here. And the trucks the men were driving, they just left them right at that spot. They didn’t even pull them to the curb. Of course, they did it with a method. It had its own method. It’s another way of protesting.

Well, the first thing that hit us in this whole thing was we got a good excuse. We can’t get to work. And we’re here.

So, it was kind of a carnival. It wasn’t half an hour before we were going into bars and saying, “No hard liquor. Serve beer and wine, if you must, but mainly beer,” and “You can stay open only if you bring your jukebox out in front and turn it on loud.” And we were dancing at 7 o’clock in the morning. Men and women. And joking, and so on. [Laughing] Feeling like, you know, God, freedom. It was marvelous.

When you’re a factory hand, you get to sit down three minutes in a day, more than your lunchtime. You figure, like, it’s a great day if you beat ‘em out of three minutes! You know?

McAuley: Yeah.

Weir: When the line would break down, it would be like I would go into laughter almost immediately, and stay there. I’d laugh at anybody’s joke – and so would everybody else – if the line, the assembly line broke down at Chevrolet.

McAuley: The CIO wasn’t supporting this General Strike then.

Weir: No.

McAuley: Did the workers stay out?

Weir: Well, those who couldn’t get to work didn’t go to work. Yeah. But the CIO was led by the Communist Party at the time. And the Communist Party supported us. I think I’ve said that here on this tape. It was me at the State CIO Convention that year that got up and challenged Dick, the Chair of the Convention. He was from the Local 6 warehouse, IOWU. His dad owned a warehouse, and he struck against his father. That’s how he got started in unionism. (I’ve forgotten his last name.)

But I said, “Where was the CIO in the Oakland General Strike? We had to stay away from work in order to participate. What is this? Where is the solidarity?”

Paul Schlitt, the Secretary-Treasurer of the CIO, got up and said, “It wasn’t a general strike. We weren’t in it.” Well, that kind of double-think, using Orwell’s term, it was a transplantation of that kind of thinking into the situation in Oakland.

But here we were, and without any leadership. By noon that day, the carnival was kind of over. We think we can’t go on like this forever. They’ll come and get us. [Laughing] Somebody will come and get us, you know, and it won’t be good. So, I had made a phone call to the Sailors’ Union to see what kind of help I could get from the seamen who were ashore and not working. And I talked to Lundeberg.

Lundeberg spoke the next night, I believe it was, at the Oakland Auditorium in the General Strike meeting. He demagogically was militant and he gave people what they wanted to hear. He denounced the City fathers and the police as people who had been reading the writings of Stalin and Hitler. He knew that it was time to get mad. He wasn’t afraid, like the rest of the officials who were afraid to get up there and even sound off.

Without any leadership, we cordoned the town off. You could get out without a union card. You couldn’t get in without a union card.

There was a guy going down the street, a great big guy with a typewriter. People said, “Hey, where are you goin’ with the typewriter?,” and he began to run. They ran and they arrested him, in effect, until he explained that he wasn’t stealing the typewriter, that he didn’t believe in the strike and he was taking his work home ‘cause he might not be able to get to work the next day. They said, “Go. Get in your car and go.”

McAuley: So, was it the residents on these blocks?

Weir: No, this was downtown.

McAuley: Alright. Well, I meant the residents of the offices that form these informal authorities for these groups.

Weir: No, it was the people who got off the buses and the streetcars. It was the truck drivers. It was the people in their cars going to work. It wasn’t the residents so much. Although in West Oakland, which is close by, the blacks involved in this strike, some of them had just walked up from there, where they lived.

But people in the offices, many were non-union. Now, the OPEIU, the office workers and the union, and the retail clerks did participate in the strike, because it was for Kahn’s and Hastings department store workers. But, that I know of, there was no general outpour of office workers – just, boom, like that – who were non-union and suddenly got the word. We did have experiences like this. Non-union people would come out and they’d be going to go home and they didn’t know for how long. They were impressed at the order, the neatness. That is, we kept the streets clean. There was no littering.

Like I say, there were people who had cordoned, we had cordoned the city off, all the streets leading out of downtown Oakland. We had downtown, 10 square blocks. Maybe it was more than that. Maybe it was more like twenty blocks.

But there was a desire to really do the right thing by everybody, everybody who was on your side. There was no rousting anybody, or anybody stealing gas from other people’s cars, or breaking in. So far as we could tell, those fifty-four hours were crimeless downtown.

It’s like in Albert Rhys Williams’ book, Through the Russian Revolution. He was a journalist and he went to Russia, because of the Russian Revolution, in February. He came back and wrote a book about what he saw. He was a good journalist.

He is walking up and down the streets of Leningrad. He sees people walking by shoe stores, for example, with broken panes, and no one is reaching inside and grabbing those shoes and running away with them. Already there was a sense of collective property. “That’s not ours just to steal. We will take care of it. We will divie that up, so to speak.”

Then, of course, I had read about Antonov Gouzenko in that book, the same book. There was open warfare between the Whites and the Reds. The Whites had captured the telephone building. I’ve forgotten whether it was Moscow or St. Petersburg, Leningrad. The Whites had captured Antonov Gouzenko, the head of the workers’ Red militia, and he’s imprisoned in the telephone building. People are shooting at one another and killing one another in this situation. The Reds are ringing and the cordon is all the way around the building. The Whites send out a Red Cross truck that they have captured, ostensibly with wounded. The Reds let the truck go through the line, the Red Cross truck, and get out around the corner, out of sight of the Whites. They grabbed the truck, and there were no wounded in it. The people inside confessed immediately that they were going for munitions. The Reds turned into a Trojan horse. They stuck highly armed people into that Red Cross truck and they went back in through a half an hour later. Zap! That was the end of that. The whites immediately surrendered.

“Where is Antonov Gouzenko? This is your neck unless you produce him.” They release him and Antonov Gouzenko is just standing there. The rest of the Reds move to kill or harm bodily all the Whites standing there who had imprisoned him.

He grabbed a gun away from someone and said, “The first one who puts a hand on any of these Whites that we’ve been fighting right now, I will shoot him.”

They said, “What? You’re going to shoot us? We’re on your side.”

He says, “I know. But you will damn the revolution by doing wrong. These people deserve a trial, like prisoners of war. You don’t represent the new (society) if you just (shoot them) because you said that they’d do it to us. Of course, they’d do it to us. But we don’t do it to them. We represent the new society.”

He had been on the streets the whole time as head of the workers’ militia. Albert Rhys Williams says that the people caught on immediately. Simply, Gouzenko was the first to become objective in this situation.

Then, the Reds led the Whites through the town, from the telephone building to the jail. Many of them were attacked and beat up by townspeople who were saying, “You got Whites?! Well, let’s get ‘em now! Let’s do ‘em in!” And the same Reds who would want to do ‘em in half an hour earlier.

They said, “No, we’re taking him. We’re going to try him.” Of course, a lot of Whites got out of jail real quick just by promising. The Reds were very lenient at that time.

But there was this morality, the feeling that ends and means have to always stick together. This is the working class itself, at the very bottom, insisting upon that, without any kind of long rationalizations about, “well, this is a special situation,” and all that malarkey. (They) just hung to it and stayed with it until the revolution itself had been starved out.

McAuley: So, in Oakland?

Weir: You could see that in Oakland. You could see the potential for that, right there in the streets.

McAuley: Mm hm. The spontaneous morality.

Weir: Yes.

McAuley: Do you think that the fact that people had just gone through the World War II experience, did that contribute in any way to this – this natural, but not always spontaneous, morality, but incredible order that took place?

Weir: I don’t know. I mean there’s no way of knowing the answer to that. I can only tell you what my feeling was. I think that there were people there who hadn’t really thought about a number of these things, that the General Strike posed for them in their minds. They approached the problem in their minds and they came up with these kinds of answers. Because the kinds of lives they lead doesn’t lead them to start moaning on the terrible people workers are; they’re lazy; they’re this or that and the other thing; or they don’t pay their rent on time; and all that. The people have nothing to gain by that. These people came up with brilliant ideas. Some of them had thought it through beforehand, in all probability. Trotsky speaks of this in The History of the Russian Revolution, that suddenly people’s minds are liberated. It staggers them. Suddenly they are free. Some of those who had been the most servile, the day before October or February, became the most bold. Zap! No one knows the exact process of the thinking of a crowd in that way.

McAuley: You saw this happen in Oakland?

Weir: In my experience, crowds of this kind, rather than being surly, lynch-mob types, or very close to that, just on the other side of the fence. No. My experience is that it is in the crowd that there is the most genius.

At the Chevrolet plant, when we had the sit-down strike, the same thing occurred. That is, I stopped people from walking out. When we all gathered together again on the loading docks of the East Oakland plant, I said, “If any of us clock out—”, but I didn’t finish my sentence. Someone said, “A lot of us will never get back in.” Someone else said, “But if we hang tough here, available for work, the moment they begin to live up to the contract and the grievance we’ve just won, then we’ll see.” No one even said, “We’ll survive.” I mean the sentence was never totally finished. Everybody understood immediately.

And that’s what we did. We stayed right there, visible, and available to work the moment that they quit reneging on the supply of gloves, which we wore out at three pair a week. It’s that same brilliance of people who have been released from the necessity to hide their feelings.