In 1920, British dockworkers in East London carried out a little-known strike. It was not simply a strike for higher wages or better conditions. British workers struck to stop the British government’s attempt to militarily crush the Russian Revolution – the first successful workers’ revolution in world history.

In 1917, after more than three years of World War I, Russian workers, peasants, soldiers and sailors rose up against the ruling classes of Russia, to end the war and build a new society with socialism as its goal. Russian workers brought to power the first workers’ state – a democracy led by the working class and responsive to its needs. It was called the Soviet Union, after the democratically-elected councils or “soviets” that were the foundation of the new system.

This workers’ state was an immediate threat to the capitalists of Britain, France, the United States and others, and their governments quickly did everything possible to destroy or contain the young workers’ state. The major capitalist nations supported Russia’s former generals and their anti-Soviet armies, sent tens of thousands of troops of their own into Russia, and sent weapons and supplies to try to crush the new state in its infancy.

The capitalists were right to be afraid. When World War I ended, class struggle was occurring throughout much of Europe. Hungary, Italy, Finland, and most importantly Germany saw worker uprisings and revolutions that almost succeeded in winning power. Britain saw a growth in trade union membership. Revolutionaries distributed literature representing the new idea of revolution coming from Russia. In 1920, the Communist Party of Britain was formed, presenting a revolutionary alternative to the old Labour Party that kept workers trapped within the confines of Britain’s capitalist government. Mutinies in the British armed forces and a wave of strikes terrified the British ruling class. The Russian revolutionary leader, Vladimir Lenin, wrote a pamphlet, Appeal to the Toiling Masses, which was widely read, urging workers in other countries to stand by the Russian workers as they defended their revolution.

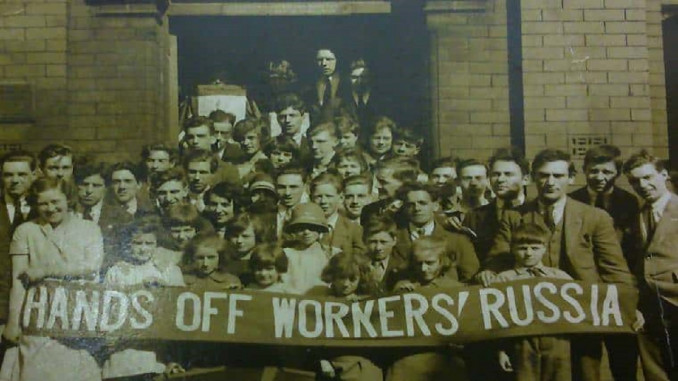

In this context, early in 1919, a coalition of some left-leaning British unions, politicians, socialist organizations and working-class suffragettes (women demanding the right to vote) organized a Hands-Off Russia campaign to keep the British government from intervening against Soviet Russia. Pamphlets were published and read, meetings were held, and a year-long organizing campaign was discussed everywhere among British workers.

Then, in Spring 1920, the reactionary Polish government began what was called the Kiev Offensive against Soviet Russia. Britain immediately agreed to send munitions to Poland to be used in this attack on the Soviet government. On May 10, British dockworkers at London’s East India dock were told to load a ship with munitions. They began work to load this ship, named the Jolly George, not knowing that they were loading arms bound for Poland.

As they loaded, they realized the truth, that the weapons were for the Polish government, and that they were to be used against the Soviet Union. Aware of the stand of their unions, the various socialist organizations, and the Hands Off Russia campaign, the workers immediately stopped work! The coal heavers, who fueled the ships so that they could sail, also stopped work, realizing that if they even fueled the ships then they could be moved and loaded at another port. For the next few days, the Jolly George and its cargo sat idle, and the local dock unions agreed to support the movement and not handle any cargo to be used against the Russian workers.

One month later, Britain’s two largest trade union organizations established a Council of Action that pledged publicly to conduct a general strike in the event that Britain take any military action against Soviet Russia. This was a major victory for the revolutionaries, as the conservative leaders of the large trade unions did not actually support revolution in Russia or anywhere else. They pledged because they felt pressure from below, from the workers, who exhibited sympathy and solidarity through their organizing and their acts of defiance. Even Lloyd George, Prime Minster of the U.K. at the time, realized the mood of the British working class, and refused to commit further British troops or material assistance to anti-Soviet forces.

This one act of London’s dockworkers certainly contributed, along with other efforts in other countries, to helping the Soviet Union survive.

Displays of international solidarity are significant because they challenge, and sometimes overcome, the artificial divisions that our ruling classes use to keep working people divided. When the British dockworkers refused to load munitions to be used against Russian workers, they not only built their own strength and sense of solidarity as a class, they also challenged the methods used by the British ruling class to continue their dominance. And they sent a message to Russian workers that other working people outside of Russia – the working class – is an international class, and all workers share the same interests. The London dockworkers action of 1920 stands as an important example of this international solidarity.

Today, the many crises of capitalism continue to punish us and promise more war and conflict in our future. To continue their plunder, the ruling classes of the world’s nations need to keep us divided – by nation, by religion, by race, by gender. In order to challenge their rule, we will need to break down these artificial barriers and see our commonality with all other working people, regardless of their nation.

With their small show of international solidarity in 1920, the dockworkers of London’s East End showed us how it can be done.