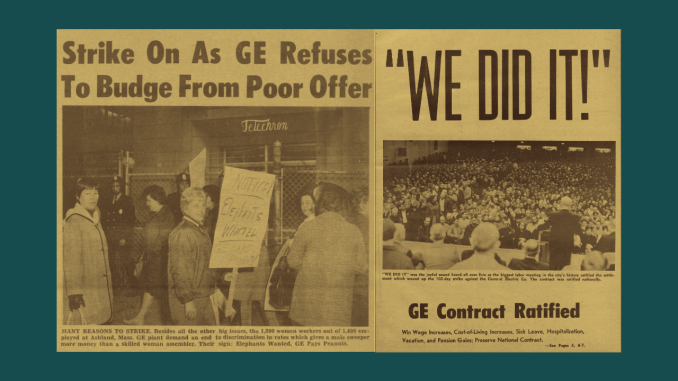

On October 27, 1969, over 150,000 workers across the United States walked out of General Electric, taking on the fourth largest corporation in the world at that time, in the largest national strike in over two decades. The strike lasted for 102 days, through the cold winter months until February 4, 1970. It involved workers in 280 plants in 33 states.

At a time when the United States government was engaged in a brutal war against the peoples of Southeast Asia, it was also at war domestically against the anti-war movement, the Black freedom movement, its own working-class population, and more. The strike at General Electric was one of the important showdowns of the time.

In the late 1960s, partially as a result of the Viet Nam war, workers in all industries were facing a spike in inflation, which was eating up working people’s wages. Much like today, the political and economic elite of the time sought to address inflation by inducing a mini-recession — slowing down the economy, slowing production, and imposing wage cuts and layoffs. Because General Electric was then one of the largest employers in the U.S., the outcome of the struggle would set a precedent in answering the question, “who should pay for the crisis?” It was a showdown that had implications far beyond the workers at General Electric.

In the years leading up to the strike, workers at General Electric faced a management that didn’t even pretend to bargain in good faith and displayed a “take it or leave it” attitude. This hard-line approach to labor negotiations even received the name, “Boulwarism,” named after G.E.’s former Vice President for Industrial Relations, Lemuel Ricketts Boulware. After a 1946 strike in which workers demonstrated their power and won major concessions from the company, Boulware became a pioneer in how to destroy unions by refusing to negotiate with unions and using dishonest public relations campaigns. He also initiated what historian Kim Phillips-Fein, in her book Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan, has called a “ceaseless education campaign in the ideology of the free-market.” The company spent millions in pamphlets, conferences, advertisements, and captive-audience meetings with their workers to convince them and the public that the so-called free market was good for them while having a union was not.

Boulware helped to aggressively spread G.E.’s anti-worker perspective in its plants and in G.E. communities. Boulware hired Ronald Reagan, at the time a declining Hollywood actor, to host a TV show called “G.E. Theater” and to travel the country giving speeches filled with G.E. propaganda. The anti-worker and conservative message in Reagan’s speeches – which opposed unions and corporate taxes, and criticized government-funded social programs – helped give Reagan the training and exposure to make his successful transition into politics.

At the same time, the situation for workers was made even more difficult because they were divided into 13 different unions (the major ones being the United Electrical Workers, International Union of Electrical Workers, United Automobile Workers and the Teamsters) who were pitted against each other by the company. In this situation, the company was able to take away the cost-of-living allowances (COLA) first won in 1946. General Electric workers faced some of the lowest wages in the industry for comparable work.

Another factor weakening unions during the McCarthy era of the late 1940s and early 1950s was that most unions had kicked out the most dedicated and effective workplace organizers because they were accused of being radicals or communists (which many of them in fact were). While the United Electrical Workers was a notable exception to this trend, and still maintained some militancy and workers’ democracy, the other major unions had already become more conservative, more bureaucratic, and less worker-led.

In anticipation of the 1969 strike, the company continued with its Boulwarist strategies, presenting its “first and final offer” weeks before contract expiration, with salary proposals for the first year that were effectively pay-cuts when adjusted for inflation. The company also demanded the right to lock out workers in the event of a strike over unresolved grievances. In addition, the company proposed that newly organized shops across the country (G.E. had already begun the practice of shutting down union workplaces and reopening them as non-union shops in other regions.) would no longer be automatically included in the national contract. This would open the door for the company to get rid of national union bargaining all together, a serious blow to workers’ power to fight for better contracts.

The workers were not going to back down in the face of the company’s aggressive tactics. They voted to reject the supposed “first and final offer” that G.E. tried to shove down their throats, and countered with four main demands — a wage increase, a restoration of COLA, a ban on dividing up plants across the country into isolated bargaining units, and a prohibition on G.E. locking out workers of one area if there were a strike in another.

Unlike in the recent past, workers insisted on a coordinated and unified bargaining approach among all of the 13 different unions. For the first time in over two decades, all of the unions were at the bargaining table together and agreed to the common set of demands.

Because the workers were united against G.E.’s attacks, the federal government recognized the threat and stepped in. The Nixon administration appointed a team of mediators who stood clearly on the side of the corporation (as is often the case with such mediators), but the workers would not be strong-armed by the federal government.

On October 27th, the strike began with strong popular support throughout society. Railroad workers in Baltimore, Maryland refused to move supplies through a picket line. Anti-war protesters and General Electric strikers spoke at each other’s rallies, recognizing the role that the company played in profiting from the war. Members of the Black freedom movement, including the Black Panthers, joined picket lines and spoke at rallies. In addition, the heads of other labor unions saw the writing on the wall, and knew what a defeat could mean for themselves and their unions. Tens of millions of dollars were donated by other unions to the G.E. workers’ strike fund.

But as in all strikes, the workers confronted a number of serious challenges. The company spent millions of dollars on media coverage to demonize the workers. Across the country, courts issued injunctions to limit the number of picketers to 10 people, effectively making the picket lines useless at blocking potential scabs. The company also attempted to provoke a “back to work” movement as the Christmas holiday season approached. It put out ads in newspapers to try and entice rank-and-file workers to cross the picket lines and end the strike. As time went on, the company attempted to divide the workers, making contract proposals for some unions but not with others. But the proposals that they offered were hardly much better than the company’s insulting proposal that led to the strike in the first place. The company’s attitude to negotiations could be characterized by a quote of one of its spokespersons who said, “It’s like the Paris peace talks. You can’t win by negotiating,” implying a war against the strikers was like a war against the Vietnamese. The company’s goal was unconditional surrender. Despite G.E.’s bluster, however, the actual balance of forces between the workers and the company was quite different.

The overwhelming majority of strikers were resolute and did not cave in. They defied the injunctions with mass picketing and held their ground against attacks by the police and National Guard, particularly in Schenectady, New York. Picketers did not back down in the face of arrests. The militant mood was expressed by a strike leader who is quoted as saying, “If you want a war, we’ll give you a war.”

In the end, the determination of the striking workers did have a powerful impact on the company, with G.E.’s profits falling 85% during the fourth quarter of 1969. The strike reportedly cost the company $79 million. The strikers forced the company to come to the bargaining table with a proposal that included a wage increase of fifty cents over 3 years, the reinstatement of COLA, sick time, vacation time, the recognition of the national contract, and more.

On February 4, 1970, the strike ended. The workers’ unity showed that it was possible to take on the giant General Electric, and that it was possible to defeat the “take it or leave it” attitude of Boulwarism.

Although these Boulwarist anti-union tactics quickly became the norm among the capitalist class, and are still a basic strategy used by the bosses to turn public opinion against workers, the struggle of the General Electric workers in 1969 and 1970 should still be an inspiration and a very important example for us today. Do companies still try to divide negotiations between different unions? Yes. Do they still start off with their last and final offer? Nearly every time. Will they still resort to injunctions and threats of legal action against workers for violating the laws that have been written to protect the corporations? Of course! But this strike is still an important reminder that when workers and our organizations unite and stand against the power of the bosses, we can win even if the system is stacked against us.

For more info on this strike, check out the booklet written by the United Electric workers.