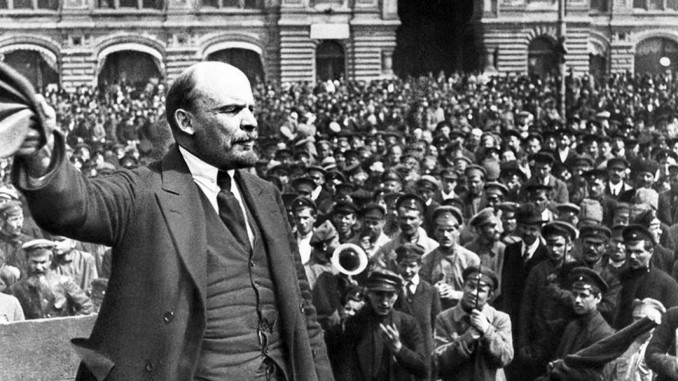

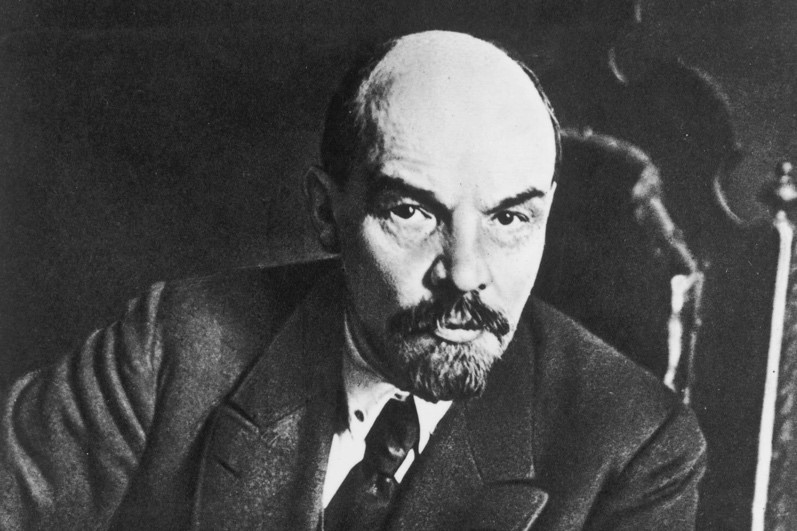

V.I. Lenin (April 10, 1870 – January 21, 1924) was an activist, one of the essential organizers of the first victorious proletarian revolution. On the occasion of the centenary of his death, it is on this basis – that of action which combines revolutionary passion and scientific rigor – that we are devoting a series of articles to show some of the achievements of Lenin and the Russian Revolution. These achievements, we believe, are essential for preparing the revolutions of tomorrow.

It is impossible to be indifferent, whether one is an opponent or a supporter of the liberation of the working class, to Lenin’s works, his achievements, his successes and his failures. For us, it is more than just celebrating a great individual with keen intelligence and total dedication to the working class cause. In our eyes, an activist is, above all, a sum of struggles and conscious experiences. To be active is to be more than oneself, it is to face the resistance of society, to accept refusal and failures, it is to learn from the struggles of the past through other experienced activists, and it is to learn from the struggles of the present and the victories of the working class. A militant participates through their experience in developing consciousness.

In this sense, a living chain of fighting traditions links us to the past. Lenin made – through the conscious choices in his life – the bridge between the lessons of the first proletarian revolution, the Paris Commune of 1871, and the first seizures of power by the working class, the revolution of October 1917. Lenin learned from the first experience of the working class taking power, the first world war, the rise of nationalism and the birth of modern imperialism. He studied and applied the insights of Marx and Engels and defended their insistence on the independent political organization of the working class. Lenin’s choices, contrary to a persistent legend, on the right but also on the extreme left, were not schematic: Lenin was flexible, and able to face the living reality of exploitation. Since his youth, he was concerned with fusing the rigorous and demanding socialist theory of Marx, with the creative, spontaneous practices of the workers’ movement, to lead the working class and the oppressed to victory, which had for a long time seemed impossible.

Lenin against the reformists: governing the bourgeois state… or destroying it?

“The working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes” wrote Karl Marx in the aftermath of the revolutionary experience of the Paris Commune in 1871.

Marx’s insight was a lesson that the Russian working class’ leaders did not seem to have learned in the aftermath of the revolution of February 1917, which overthrew the Russian tsar’s regime.

When Lenin returned from exile a month after the revolution began, he found a country ruled by a liberal bourgeois provisional government – a government which continued the war without acceding to the demands of workers and peasants but which nevertheless benefited from the support of the workers’ movement, including the leadership of the Bolshevik Party.

On April 7, Lenin published an article in the newspaper Pravda, The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution, better known under the title of the April Theses. He insisted on the need to fight the bourgeois government and to oppose it with the power of the workers’, peasants’ and soldiers’ councils, the soviets.

The task of the exploited, of the proletariat, and of the party which claims to represent them, was not to support a government with more democratic pretensions than the former monarchical power. This government, which claimed to be democratic, put off the question of elections until after the war. The task of the working class was not to continue the war to defend a so-called “revolutionary homeland”. The workers and peasants had nothing to gain by supporting a new parliamentary democracy which would preserve the power of exploiters, the landowners and factory owners.

To put an end to the exploitation and barbarity of the war, the task of the proletariat was, on the contrary, to organize itself completely independent of its enemies, starting with the government which represents them. It had to seize power, with its own organizations, the soviets, and take control of the economy and of all society, getting rid of the state apparatus of the bourgeoisie.

The soviets were born in May 1905, in the industrial center of Ivanovo-Voznesensk, during a general strike in which 30,000 workers came together and formed a workers’ council, the soviet, to lead the strike. The soviet also took control of the bosses’ printing presses, to allow freedom of expression, and carry out collections to help the unemployed, and ensure the basic protection of peoples’ rights in place of the police… A committee of soviets linking all the factories was elected to respond to a concrete need for coordination of the struggle.

This soviet power thus entered into competition with the tsarist government’s power in the city. It confirmed the capacity of the working class to take care, not only of its economic affairs, but even to lead the whole of society.

Subsequently, Bolshevik activists understood that the soviets could be the basis of the proletariat’s seizure of power.

Understanding the nature of the state after the Paris Commune

Already after, after the Paris Commune, Marx had understood that the power of the exploited class, the dictatorship of the proletariat, could only be exercised by destroying the institutions of the old bourgeois state apparatus.

The state is not a “neutral” instrument which only requires a change of personnel to obtain radical social changes. The state is an instrument of domination: that of one class over another. This was the case then as it is today. The state is a tool of the exploiters to control the exploited, a government of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat.

A state might not intervene in the economy, it might not control currency, it might leave control of health or education to the private sector, but what no state can do without is its armed force. The police and the army are the state’s means to enforce fundamental laws, such as private ownership of the means of production.

If a government and a parliament were to put in place laws going against this right of property, (for example by expropriating sectors of the economy), the armed force of the state, loyal to the bourgeoisie and its system, would turn against that government or parliament in a coup. Only the mobilization of workers would make it possible to impose such measures, to take control of the means of production and prevent their former-owners from recovering them. Only such a mobilization would allow the working class to gain confidence in their strength and in their ability to direct society itself, and therefore to get rid of the parasites who feed off of their work.

The Paris Commune, Marx wrote, was “essentially a working class government, the product of the struggle of the producing against the appropriating class, the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labor.”

A “political form at last discovered” because it was born from practice, from concrete struggle, not from theories or the imagination of intellectuals outside the working class. An unprecedented democratic political form, with decisions voted directly in assemblies and elected officials able to be dismissed by those who had elected them, earning no more than the average salary of a worker. A democratic form ensuring to everyone freedom of expression, access to education, and the guarantee of being able to live decently. This is what the first workers’ power was: a power born of the suppression of permanent armed bodies and their replacement by the armed people.

This power did not go through with the destruction of the old state machine or private property, and it did not take the initiative against the army of the bourgeois government, stationed in Versailles.

To go to the end of the struggle for workers’ power is to expropriate the bourgeoisie of the means of production for the benefit of the entire working class, under its control, in order to organize production according to its needs. It is also to prevent the ruling class from regaining its power, by destroying its army, its police, its bureaucracy. This is what Marx and Engels called the “dictatorship of the proletariat”: the power of the majority of the population, the class of the oppressed and exploited, in order to establish the conditions of a society without social classes, without exploitation or oppression, and therefore without a state since without the need for one class to dominate another, there would be no need for a state. This would be a true communist society.

The State and Revolution

In July 1917, the government violently suppressed the workers’ revolt in Petrograd. Lenin then took refuge in Finland, where he developed his analysis of the state by writing The State and Revolution: the Marxist theory of the state and the tasks of the proletariat in the revolution. It was only published after the October Revolution.

He clarified the disagreements between revolutionary Marxists and reformists who claim to achieve workers’ power through bourgeois institutions. He criticized the reformist socialists who, in Russia as in Germany or France, still supported the butchery of the First World War – then described by Lenin as the “first great imperialist war”. The reformists did so in the name of defending so-called democratic or social achievements that they were able to obtain. In other words, the reformists’ crime was not only to give workers the illusion that they could end exploitation without destroying the state, they also sacrificed the flag of internationalism on the altar of national chauvinism. They abandoned the slogan of Marx and Engels “Proletarians of all countries, unite” in favor of national union under the leadership of “their” bourgeoisies. The reformist policy was, in fact, guilty of nearly ten million deaths, proletarians sent to kill each other in the trenches to defend the interests of their exploiters. This was an unspeakable betrayal on the part of those who dare to claim to be socialists.

To this betrayal, the proletariat of Russia responded with revolution, with the power of the soviets, to end the war, collectivize agricultural land, and place factories under workers’ control. Lenin also distinguished his theory from that of the anarchists who would like to immediately abolish all forms of state. For anarchists, or libertarian communists, it would be possible to organize production on a local scale, to multiply “free communes” in which the sharing of goods would be ensured, without the need to defend them with a workers’ state. This would neither allow the means of production to be developed on a scale necessary to meet the needs of all, nor would it allow the working class to arm itself against a bourgeoisie capable of organizing itself nationally with the support from other capitalist governments. Revolutionary Russia provided a vivid demonstration of this problem as it was attacked, not only by the White Army of counter-revolutionaries, but also by other countries’ armies.

The phase of dictatorship of the proletariat remains a necessity. But in this phase, the state is doomed to disappear.

A debate that is still relevant today!

In 2017, Jean-Luc Mélenchon of the left party, La France Insoumise (LFI), promised that voting for him would “save us thousands of demonstrations”. As if the left in power, under Mitterrand or Jospin for example, had not delivered attacks on the working class, requiring many demonstrations!

In January 2023, Fabien Roussel of the French Communist Party (PCF) did not refuse in principle to participate in a government which would go “in the direction of defending the interests of the country, of the workers.” As if the interests of “the country”, those of the French bourgeoisie, were not intrinsically contradictory with those of the workers!

In the meetings of LFI, as in those of the PCF, we see them wave the tricolor flag and we sing La Marseillaise, symbols which trap us doubly: on the one hand by dividing our class according to the nationality, and on the other hand by uniting those who are of French nationality with the French bourgeoisie. A French worker and a French boss have nothing in common. Whereas a French worker and a worker from the other side of the world belong to the same class that runs society, gets exploited, and can turn the tables and change everything!

Our disagreements with Melanchon’s LFI and the PCF go well beyond simple “nitpicking” about the demands that we can make in our respective programs. They concern our conception of the nature of the state and the role of the working class in fighting for its emancipation.

We have seen all too well how, all over the world, left-wing parties in power pursued the same capitalist policies as openly bourgeois parties. And for good reason! To give the prospect of delegating power to professional politicians, with respect for the institutions of the bosses’ state, and to passively expect the application of electoral promises, is to disarm the workers against the employers who never give in.

To the workers, we give the perspective of independent organization and unity of the working class, against all the false chauvinistic, racist or sexist divisions which only weaken the workers power. This perspective will allow the working class, in struggle, to reconnect with the experiences of the past and to find new forms of organization, to complete its struggle and finally establish a new society.

Lenin against Stalin: the State without revolution

A past that does not pass

Stalinism has deeply marked the history of the workers’ movement. To be “communist” is, in fact, even with regard to Lenin, to be equated with the political regime – the Stalinist dictatorship – which falsely gave itself the name, “communist”.

An article published in Mediapart on January 21, 2024, with the significant title, “One hundred years later, how Lenin’s thought survives Leninism”, by Mathieu Dejean, Fabien Escalona and Romaric Godin, quotes Marina Garrisi:

If the political and human divide which separates Lenin from Stalin is documented, the bureaucratization of the Soviet state […] does not begin with the death of Lenin nor with Stalin’s accession to power. Lenin was certainly hostile to bureaucracy, but had an insufficient understanding of it and reduced it (too often) to relics inherited from the tsarist past.

Our aim is not to polemicize with this particular quote, but with the overall thesis of the article. The authors, like all defenders of the dominant ideology, would like Stalin to be the inevitable successor of Lenin, to consider the bureaucratic degeneration of the Russian revolution as its continuation, and to identify the dictatorship of the Stalinist bureaucracy with the dictatorship of the proletariat. Their goal is to paint Stalinism as the logical continuation of Leninist communism, reproaching the latter for having made the former possible. They are happy, in fact, that Stalin emerged to discredit Lenin!

Class struggle in Soviet Russia

The period from 1917 to 1927 was a period when the class struggle was exacerbated in the world. Its exacerbation was manifested by the evolution of the Soviet regime. In 1927, the Left Opposition suffered a lasting defeat, following the crushing of the Canton Commune, a crushing which put an end to the second Chinese revolution. The political events that occurred during this period can therefore in no way be described as conflict based on personal interests, clan warfare, or the psychology of the Bolshevik leaders. On the contrary, the triumph of the bureaucracy led by Stalin was the result of a fierce class struggle in the world and in the USSR itself. It is this class struggle that changed the USSR, to the point that a foreigner who had made the same trip ten years apart would have found the country unrecognizable, and would have believed he was visiting two different countries, whose regimes had contradictory policies.1

Can we then criticize Lenin for not having “understood everything” about the nature of this unique social phenomenon? Can we blame him for not foreseeing the birth of a regime whose power was no longer exercised by the working class, but was not necessarily exercised by the bourgeoisie? If the exercise of power by a bureaucracy is a phenomenon common to practically all bourgeois states, nowhere are these bureaucracies so detached from the dominant class on whose behalf they exercise power. The Soviet bureaucracy was different, emerging from, but completely independent of the working class, and working against it. When Lenin died in January 1924, he had clearly identified the monstrous development of the state bureaucracy, and he had clearly perceived its incarnation in Stalin, but the game was far from over. In 1924, the revolutionary crisis opened throughout the world by the Russian Revolution was far from over. It was only in 1936 that Trotsky ended up analyzing the phenomenon of the bureaucracy in his book The Revolution Betrayed, which was preceded by three other pamphlets2 and hundreds of texts. It took many confrontations and debates, to develop an overall theory and a coherent policy in the face of the Stalinist bureaucracy.

There is one criticism that we cannot make of Lenin – that of not having identified this bureaucracy, and though he wasn’t able to completely characterize it, he fought it to his last breath.

The threat of isolation from the revolution

If the Russian working class at the head of the October Revolution, rallying the peasantry, had established the first workers’ state in the world, the fact remains that this working class, a very small minority, was at the head of an economically backward, poorly industrialized country. Some 75 years earlier, Karl Marx had written: “A development of the productive forces is the absolutely necessary practical premise (of Communism), because without it want is generalized, and with want the struggle for necessities begins again, and that means that all the old crap must revive.”3 It was precisely this “development of productive forces” which was lacking in Russia.

We must at no time lose sight of the fact that the entire policy of the Bolshevik party, and of Lenin in particular, was based on the prospect of a victory of the revolution in the West. A victorious German proletariat, in one of the most industrialized countries in the world, would have supplied Soviet Russia with machines and manufactured products, and would have provided it with tens of thousands of highly qualified workers, technicians and managers, in return receiving food products and raw materials. If the revolution in Germany had triumphed in 1918, the economic development of the USSR, like that of Germany, would have continued by leaps and bounds and would have changed the destiny of Europe, and even the whole world. But the German revolution of 1918-1919 was crushed under the leadership of reformist socialists, the social democracy.

From “war communism” to the NEP

After the failure of the German revolution, “war communism” was imposed for years as an internal measure necessary for the survival of the Soviet regime faced with civil war. This meant that economic life was exclusively subordinated to the needs of the war.

The year 1921 was pivotal: production continued to decline, not only because of the war, but also because the peasants did not receive payment for their products, and therefore had no interest in producing more than they needed for themselves. At the beginning of 1921, there were more than fifty centers of peasant insurrection on the Don, the Kuban, and in Ukraine. The most obvious symptom of peasant revolts, a decay of the Soviet state and a weakening of Bolshevik power, was the Kronstadt revolt. Kronstadt and the peasant revolts risked being anchor points for a return of the imperialist powers who had lost control of Russia with the defeat of the counter-revolutionary armies in the civil war. However, even after these revolts were suppressed, nothing could force the peasants to sow more crops. Famines led to hundreds of thousands of deaths, and looting by gangs was commonplace (including by gangs of children orphaned by the civil war).

When the 10th congress of the Communist Party of Russia (Bolshevik)4 opened in Moscow in March 1921, the delegates and participants could nevertheless congratulate themselves, because, as Lenin noted in his opening speech: “It is the first time that our congress is being held while the territory of the Soviet Republic is freed from enemy troops, supported by capitalists and imperialists from around the world.”5 The young workers’ state had indeed defeated the counter-revolution… but at what cost? The industry was only producing 20% of its pre-war level in terms of volume. Cast iron production was only 2.4% of the 1913 level, while steel was at 4%, cotton at 4%, and sugar at 5.8%. The value of manufactured goods was only one-eighth that of 1912.

The fight against time: Lenin, the NEP and party unity

It was therefore in this alarming context that the 10th Congress instituted the New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP consisted of replacing grain requisitions with a tax in kind, restoring freedom of trade within the borders of the USSR. The essential point of the NEP was the restoration of the market, its mechanisms and its institutions. These were necessary concessions made to the peasantry so that they could resume production and feed the country. But along with the market economy came the old social classes: wealthy peasants, old and new industrialists, businessmen who traded goods between the city and the countryside, and all the social differentiation specific to bourgeois society. The risk was that all these “kulaks” (the rich peasants) and these “nepmen” (the old and new bourgeoisie) would find a political expression favorable to the restoration of commercial and other relations with the international bourgeoisie. This political expression would necessarily be hostile to the revolution and to the power of the Bolsheviks.

The decline of the working class and the rise of the apparatus

At the same time as the rise of the NEP bourgeoisie, in 1921, to use Bukharin’s expression, there was a real “disintegration of the proletariat”. The working class went from 3 million in 1919, to 1.25 million in 1921. Cities threatened by famine were literally emptied. The population of Petrograd had fallen by more than half, that of Moscow by 45%, and in the provincial capitals by one third.

The workers undoubtedly played a leading role in the seizure of power in October 1917. During the civil war, they provided the most dedicated cadres to the Red Army and the soviet administration. These governmental tasks absorbed the ranks of the working class, particularly in the sectors where its vanguard was recruited: metalworkers, railway workers or miners. Lenin noted this in a speech delivered on November 20, 1922: “The forces of the proletariat were above all exhausted by the creation of the apparatus.”6

Two years after the seizure of power, the Soviets were gradually emptied of their participants and their activities. The civil war had put the army in a position of greater autonomy in relation to the soviets. The apparatus of the workers’ state, failing to mobilize a working class which was deserting the soviets, was held together entirely by the party. “The bourgeoisie,” Lenin said, “understands well that in reality “the forces of the working class” now consist of the powerful vanguard of this class: the Russian Communist Party.”

Indeed, the decline of the working class did not prevent the party from growing: in March 1919, the party had 250,000 members, a year later, 610,000 and, in March 1921, 730,000. The rise of the party apparatus, combined with the social vacuum left by the desertion of the soviets, encouraged opportunists from all over the country to join it en masse. A 1919 census already provided information on the social origin and jobs of party members: only 11% were industrial workers and 53% worked at various levels of the soviet state. This is how the process of “functional differentiation” began, that Christian Rakovski described in 1928 in the work written in exile in Saratov, more than 700 kilometers from Moscow, The Professional Dangers of Power7:

The function has modified the organism itself; that is to say that the psychology of those who are charged with the diverse tasks of direction in the administration and the economy of the state, has changed to such a point that not only objectively but subjectively, not only materially but also morally, they have ceased to be a part of this very same working class. Thus for example, a factory director playing the satrap in spite of the fact that he is a communist, in spite of his proletarian origin, in spite of the fact that he was a factory worker a few years ago […] If we pass to the party itself, in addition to all the other shades which can be found in the working class, it is necessary to add those who have transferred from other classes. The social structure of the party is far more heterogeneous than that of the proletariat. It has always been so, naturally with the difference that, when the party had an intense ideological life, it fused this social amalgamation into a single alloy thanks to the struggle of a revolutionary class in action.

Trotsky later provided these additions to understand the psychology of future bureaucrats and their relationship to the workers’ state: “The demobilization of a red army of 5 million men was to play a considerable role in the formation of the bureaucracy. The victorious commanders took important positions in the local soviets, in production, in the schools, and this was to stubbornly bring everywhere the regime which had made them win the civil war. The masses everywhere were gradually eliminated from effective participation in power.”8

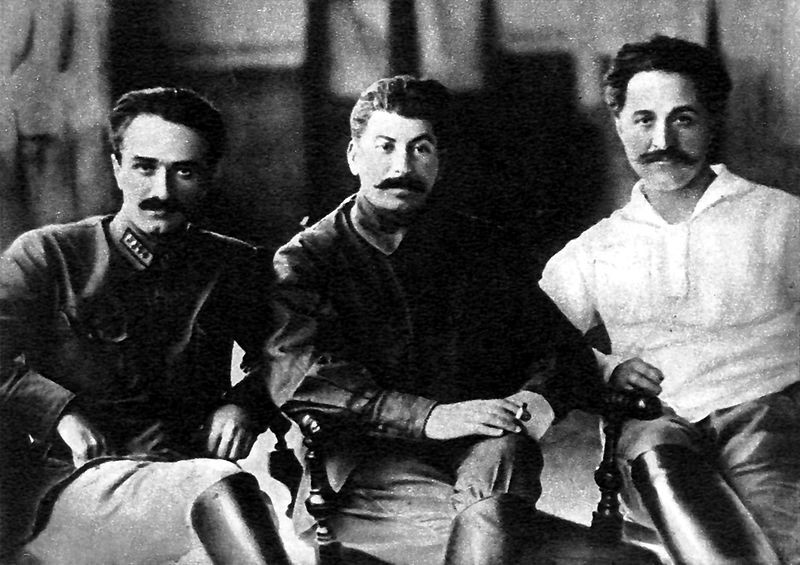

So here was this new bureaucratic caste which has appeared in the factories, in the soviets and in the party. This was the situation when the Soviet state took the turn towards the NEP in 1921. However, the year 1921 was also the year when the pace of the world revolution slowed down. It was in this context of decline of the world revolution and entrenchment of the bureaucracy that the election of Stalin to the post of general secretary of the party at the 11th Congress in April 1922 took place.

“Lenin’s Last Struggle”9

A man of Lenin’s stature could not fail to grasp the risks of degeneration that the victory of the revolution and its isolation in a backward country entailed.

On November 13, 1922, at the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, he reported on the difficulties facing young Soviet Russia:

Why do we do these foolish things? The reason is clear: firstly, because we are a backward country; secondly, because education in our country is at a low level and thirdly, because we are getting no outside assistance. Not a single civilized country is helping us. On the contrary, they are all working against us. Fourthly, our machinery of state is to blame. We took over the old machinery of state, and that was our misfortune. Very often this machinery operates against us. In 1917, after we seized power, the government officials sabotaged us. This frightened us very much and we pleaded: “Please come back.” They all came back, but that was our misfortune. We now have a vast army of government employees, but lack sufficiently educated forces to exercise real control over them. In practice it often happens that here at the top, where we exercise political power, the machine functions somehow; but down below government employees have arbitrary control and they often exercise it in such a way as to counteract our measures. At the top, we have, I don’t know how many, but at all events, I think, no more than a few thousand, at the outside several tens of thousands of our own people. Down below, however, there are hundreds of thousands of old officials whom we got from the tsar and from bourgeois society and who, partly deliberately and partly unwittingly, work against us. It is clear that nothing can be done in that respect overnight. It will take many years of hard work to improve the machinery, to remodel it, and to enlist new forces.10

Lenin’s speeches and articles from 1920 to 1922 multiplied references to this bureaucracy. But, in Pravda of January 3, 1923, Sosnovski describes how those who applaud Lenin’s speeches nevertheless change nothing in their practices:

Lenin often emphasized that the apparatus of office functionaries often makes itself master of us, while it is we who should be the masters. And everyone applauded Lenin, and also the commissioners, the leaders, those in charge. […] They applaud wholeheartedly, because they completely agree with Lenin. But take the buttons of his jacket one by one and ask him: “So, the machine in your office has also made itself master of its boss?” He will look outraged: “It’s not the same. This is absolutely correct, but only for the other, for the neighbor. I have my device in hand.”11

Upon his return to political activity, after his first stroke, Lenin focused on the problem of this rising bureaucracy. Complaining about the “communist lies and boasts” which made him “horribly heartbroken”, he looked among his fellow fighters for the ally he needed to take the offensive. It was in November 1923 that he proposed to Trotsky “a bloc against the bureaucracy in general and against the organizational bureau in particular”.12

The Georgian drama

In the days that followed, Lenin suffered a real “shock” with the revelation of the events that took place in Georgia.

The Red Army entered Georgia in 1921 to support a Bolshevik “insurrection.” Resistance to Russian domination was reflected in a very strong national feeling, including among Georgian communists. In 1922, the Georgian Communist Party stood against the plan of the Commissar for Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, which envisaged the formation of a federated republic including Georgia and intended to join the USSR. Stalin was supported by his friend Ordzhonikidze, secretary of the national office of Transcaucasia (to which Georgia belongs). Lenin then accused Stalin of being “too hasty,” but since Stalin’s plan had been approved by the central committee of the Russian party, he called on the Georgian communists to submit to party discipline.

The Georgian communists refused to give in. Ordzhonikidze, covered by Stalin, then undertook to break their resistance by apparatus methods: he dispersed them to the four corners of the country and forced the Georgian central committee to resign, with violence and police repression as a result. The Georgian leaders nevertheless appealed to Lenin and managed to pass on to him a damning file on the activity deployed against them by Stalin, who was trying to filter the information so as not to tire out the already sick “old man.”

Lenin then discovered the extent of the disaster13 and prepared for a definitive response against Stalin: the “powerful forces which divert the Soviet state from its path must be designated: they emanate from an apparatus which is fundamentally foreign to us and represents a hodgepodge of bourgeois and tsarist survivals”, “covered only with a soviet varnish”. Against Stalin, who was Georgian, clearly designated in the discussion, he launched an attack:

The Georgian [Stalin] who is neglectful of this aspect of the question, or who carelessly flings about accusations of “nationalist-socialism” (whereas he himself is a real and true “nationalist-socialist”, and even a vulgar Great-Russian bully), violates, in substance, the interests of proletarian class solidarity, for nothing holds up the development and strengthening of proletarian class solidarity so much as national injustice.14

These lines were dictated on December 30 and 31, 1922; on January 4, he added to his will the postscript on Stalin, whose brutality he denounced and whom he recommended be removed from the party’s general secretariat. He transmitted the Georgians’ file to Trotsky, asking him to take charge of their defense, that is to say, the devastating report against Stalin.

Then he made the attack publicly in articles published in Pravda, entitled “Inadequacies of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection”, Stalin’s department, and “Better, fewer, but better”. In this last article, he condemned Stalin without naming him: “Things are disgusting with the state apparatus”, “there is no worse institution than the Inspectorate”, “the bureaucracy must be destroyed, not only in soviet institutions, but in party institutions.” As Pierre Broué says, for all informed readers, it is a “bomb”: Lenin violently and publicly attacked Stalin. Members of the politburo were hesitant to publish the article, some even proposing to publish only one copy, which would only be shown to Lenin. The article was still published and Lenin continued the offensive. On March 9, he suffered a third stroke which permanently deprived him of the use of speech. Stalin could breathe easy: the party was now deprived of its head at the height of the struggle against the bureaucracy.

Lenin: one of the first “communists against Stalin”15

Lenin died on January 21, 1924. It took more than four years for the bureaucracy to strengthen itself to the point of exercising undivided power. To crush the working class and the poor peasant in Russia, it supported the peasant bourgeoisie revolting against workers’ power. Each failure of the world revolution – in Germany in 1923, in China in 1925 then in 1927 – consolidated its power in the USSR by weakening the working class.

Taking advantage of each defeat of the working class in the USSR, as in the world, it ended up establishing its domination at the head of a workers’ state now subject to a long process of degeneration. The bureaucracy dismissed the opposition of the old Bolshevik guard, those who had led the October revolution, relying on the Nepmen and the rich peasants, the kulaks. Then, it had to turn against them, when the kulaks threatened the bureaucracy by threatening the workers’ state it had taken over.

After a century of class struggle and many betrayals, the bureaucracy, or rather the bureaucrats, who aspired to perpetuate their privileges by transforming themselves into bourgeois owners of property, dealt the last blows to the Soviet state. But the end of the USSR is by no means the end of Leninism: the fight for the triumph of communism continues!

- Panaït Istrati, Towards the other flame, I, Confession for the vanquished, “After sixteen months in the USSR Confessions for the vanquished. », ed. Rieder, 1929 and ed. “Folio” Gallimard, 1987. ↩︎

- Trotsky, Bolshevism versus Stalinism, Workers’ State, Thermidor and Bonapartism and Again and Again on the Nature of the USSR. ↩︎

- Quoted by Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, chap. 3, ed. Midnight, 1963, p. 44. ↩︎

- Communist (Bolshevik) Party of Russia. ↩︎

- Lenin, “Opening speech” of the 10th congress of the PC(b)R, March 8, 1921, Complete Works, volume 32, Social Editions, 1963, p. 173. ↩︎

- Lenin, Complete Works, volume 33, Social Editions, 1963, p. 447-456. ↩︎

- Rakovski, The professional dangers of power, in On bureaucracy , ed. Maspero, coll. “Red Books”, 1971, p. 124-125. ↩︎

- Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed, chap. 5, ed. from Minuit, 1963, p. 65. ↩︎

- Title of the work by Moshe Lewin, whose reading is recommended: Lenin’s Last Struggle, ed. from Midnight, 1967. ↩︎

- Lenin, “Report presented to the 4th congress of the Communist International”, November 13, 1922, Complete Works , t. 33, ed. Sociales, 1963, p. 440-441. ↩︎

- Quoted by P. Broué in The Bolshevik Party, chap. 8, ed. from Minuit, 1963, p. 173. ↩︎

- Trotsky, My Life , Chapter 39, ed. Gallimard, 1953, p. 485. ↩︎

- Lenin, “The question of nationalities or “autonomy””, December 30, 1922, Complete Works , t. 36, ed. Sociales, 1963, p. 618. ↩︎

- Lenin, “The question of nationalities or “autonomy”” (Continued), December 31, 1922, Complete Works , t. 36, ed. Sociales, 1963, p. 620-623. ↩︎

- Title of a work by Pierre Broué on the Left Opposition, then “Trotskyist” in the USSR, Communists against Stalin, the massacre of a generation , ed. Fayard, 2003. ↩︎