In 1934, the auto parts manufacturing center of Toledo, Ohio was in the grip of the Great Depression, which began with the 1929 stock market crash. One in three workers in this city of 275,000 were unemployed and on relief. The rest of the Toledo working class experienced short work weeks and wage cuts imposed by the capitalists whose companies operated on the edge of bankruptcy.

One such company was Electric Auto-Lite, which made lighting and ignition systems for Chrysler and other auto companies. Auto-Light was owned by Clem Miniger. Miniger also controlled the Ohio Bond and Security Bank. Miniger boasted a net worth $84 million in 1929 – in today’s money he would be worth 1.5 billion dollars.

The Ohio Bond and Security Bank went bankrupt in 1932. When it collapsed, it wiped out the life savings of thousands of workers. The failure of the bank also caused the collapse of dozens of Toledo companies which had deposits there, which in turn left thousands of workers without jobs. Miniger got his own money out just before his bank officially went bust. Working-class Toledo muttered, “We don’t need Dillinger – we have Miniger,” comparing the company boss to the famous bank robber John Dillinger. His home had to be protected by armed guards.

Auto-Lite employed about 1,000 workers at the beginning of 1934. Wages were low by comparison with other auto-parts companies. There was speedup. Workers only had a few hours of work in weeks when orders were falling off. Provoked by the threat of more wage cuts, about 400 Auto-Lite workers struck on February 23, 1934, along with workers from three smaller plants. The strike was only partly effective and the Auto-Lite strikers went back to work on the promise that Miniger would negotiate a contract with their newly formed Auto Workers Federal Union local in the near future.

On April 12th, tired of waiting for the company to start negotiating, union workers went out on strike. The company responded by getting a judge to issue an injunction that limited pickets at the plant. Within three weeks, the bosses had gathered some 1,800 strikebreakers at Auto-Lite.

However, Toledo socialists and communists had been organizing the unemployed to fight for higher relief payments and also to support the struggles of striking workers. Their organization was called the Lucas County Unemployed League. Small numbers of League members joined the minority of Auto-Lite workers who set up picket lines.

The bosses quickly got an injunction to stop the picketing, hoping the strike would collapse. However, two Unemployed League officers, along with several local union members, sent a letter to the judge informing him that they would break the injunction and encourage mass picketing. The letter read:

Honorable Judge Stuart:

On Monday morning, May 7, at the Auto-Lite plant, the Lucas County Unemployed League, in protest of the injunction issued by your court, will deliberately and specifically violate the injunction enjoining us from sympathetically picketing peacefully in support of the striking Auto Workers Federal Union….

Therefore, with full knowledge of the possible consequences, we openly and publicly violate an injunction which, in our opinion, is a suppressive and oppressive act against all workers.

Sincerely yours,

Lucas County Unemployed League

Anti-Injunction Committee

Sam Pollock, Secretary

On May 7th, the picket lines were still small. The picketers, including the members of the Unemployed League, were arrested but the Judge did not order them jailed, only warning them to stay away from the plant. Nevertheless, the arrested workers walked right back to the picket line directly from court. The League’s defiance encouraged more of the unemployed to join the pickets. So did members of other Toledo unions, which up until then had stayed on the sidelines. Soon, more than 10,000 people were turning out to the picket line.

On May 23, as country deputies were massed on the roof of the Auto-Lite plant, with tear gas aimed at strikers, a strikebreaker from inside the plant threw a bolt out of a plant window and hit a picket, Alma Hahn, sending her to the hospital. Picketers grew angrier, as more police showed up and began beating individual strikers.

When the cops tried to escort strikebreakers out of the plant, picketers responded with a barrage of bricks. Tear gas bombs rained down from the factory windows, as company thugs wielded bats and fired a water hose at the crowd.

At one point, strike supporters, choking from the tear gas fumes, fell back, but only to regroup. In the end, the police and company thugs were the ones to retreat. A socialist journalist from Toledo, Art Preis, wrote:

“Choked by the tear gas fired from inside the plant, it was the police who finally gave up the battle. Then, the thousands of pickets laid siege to the plant, determined to maintain their picket line.”

The workers improvised giant slingshots from inner tubes. They hurled whole bricks through the plant windows. The plant soon was without lights. The scabs cowered in the dark. The frightened deputies set up machine guns inside every entranceway. It was not until the arrival of 900 National Guardsmen, 15 hours later, that the scabs were finally released, looking a sorry sight, as the press reported it.

What happened next was one of the most amazing battles in U.S. labor history. With their bare fists and rocks, the workers fought a six-day pitched battle with the National Guard. They fought from rooftops and from behind billboards and came through alleys to flank the guardsmen. “The men in the mob shouted vile epithets at the troopers,” complained the Associated Press, “and the women jeered them with suggestions that they ‘go home to mama and their paper dolls.’”

But the strikers and their thousands of sympathizers did more than shame the young National Guardsmen. They educated them and tried to win them over. Speakers stood on boxes in front of the troops and explained what the strike was about and the role the troops were playing as strikebreakers. World War I veterans put on their medals and spoke to the boys in uniform like “Dutch uncles.” The women explained what the strike meant to their families. The press reported that some of the guardsmen just quit and went home. Others voiced sympathy with the workers

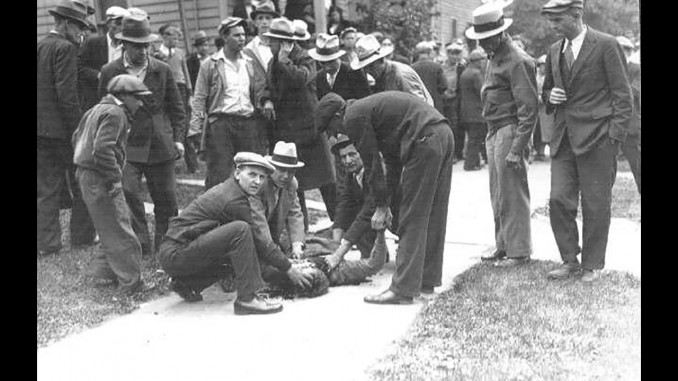

On May 24, some guardsmen fired point-blank into the Auto-Lite strikers’ ranks, killing two and wounding 25. But 6,000 workers returned at dusk to renew the battle. In the dark, they closed in on groups of guardsmen in the six-block martial law zone. The fury of the onslaught twice drove the troops back into the plant. At one stage, a group of troops threw their last tear gas and vomit gas bombs, then quickly picked up rocks to hurl at the strikers; the strikers recovered the last gas bombs thrown before they exploded, flinging them back at the troops.

On Friday, May 31, the troops were speedily ordered withdrawn from the strike area when the company agreed to keep the plant closed. This had not been the usual one-way battle with the workers getting shot down and unable to defend themselves. Scores of guardsmen had been sent to the hospitals. They had become demoralized. By June 1, 98 out of 99 AFL local unions had voted for a general strike.

A monster rally on the evening of June 1 mobilized some 40,000 workers in the Lucas County Courthouse Square. By June 4, with the whole community seething with anger, the company capitulated and signed a six-month contract, including a 5% wage increase on top of a provision setting minimum pay 5% above the minimum pay set up in government regulations.

In the early years of the Depression bosses assumed that it would be easy to play unemployed workers off against workers on strike. It was a key part of their tactic to stop workers from building fighting unions which could counter the bosses’ tactics for pushing wages down to sustain profits in the midst of a depression. But a large part of Toledo’s unemployed workers could see through Boss Miniger’s divide-and- conquer strategy. The willingness of the leaders of the Unemployed League to personally stand up to the injunction gave workers, both strikers and the unemployed, confidence that these leaders could be counted on. What the Toledo workers accomplished was far more important than just winning the battle at Auto-Lite; they showed workers all over the country that workers, both employed and unemployed, once united, could beat the boss and even the soldiers. At any time, we could be confronted by a downturn in this economy, run by the big corporations and banks, and we know it will be us workers who pay the price. The example of the Toledo Auto-Lite strike will come in handy – the unemployed and the employed can work together, and become an unstoppable force. This is a truth that the bosses of today hope we never discover for ourselves.