On December 7, 1941, Japan bombed the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack on Pearl Harbor did not come out of nowhere. It was the culmination of growing economic competition, including sanctions, over which of these two empires would control the resources and markets of the Asian Pacific. The attack brought the United States into the ongoing world war, in which it would fight alongside the Allied Powers of the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union against Japan and the other Axis powers, principally Germany and Italy. This war was meant to settle which superpowers would rule not only the Pacific, but the rest of the world as well.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, a bitterly anti-Japanese climate was fomented in the United States by the government and the mainstream press. Within hours, over 1,000 Japanese community leaders were rounded up by the FBI and arrested without evidence or due process. Political leaders militantly spouted racist and pro-war nationalist arguments against the Japanese.

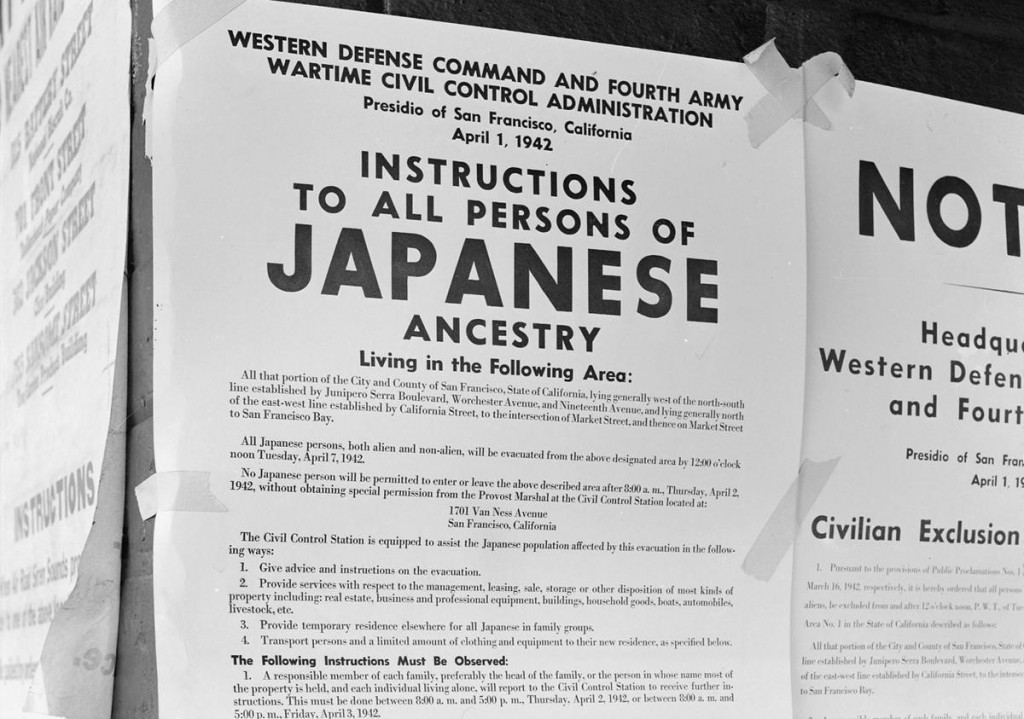

Two months after the attack, on February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, resulting in the relocation and internment of an estimated 120,000 people of Japanese background. It was a sudden mass incarceration, with no trial or jury. The U.S. military rounded up these people and sent them to ten prison-like camps operated by the military in deserted parts of California, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado and Arkansas. In the spring of 1942, further evacuation orders were declared in cities across the West Coast, in many cases, telling people that they only had a week or less to relocate. People were told to bring only what they could carry. They were forced to abandon their homes and businesses. Families and loved ones were split up.

Roughly two-thirds of those who were interned were native-born U.S. citizens, or “Nisei children.” The main architect of the internment program, Colonel Karl Bendetsen, famously said, “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp.” Over 2,000 internees were Japanese people living in Latin America who were captured by the U.S. and sent to the camps in the Western United States. While the largest numbers of detainees by far were of Japanese descent, approximately 11,500 Italian- and German-Americans were also sent to internment camps.

Despite the fact that internees were kept in by barbed wire and military police, the camps were both prisons as well as cities with their own schools, post offices and workplaces. Internees were employed with extremely low wages to produce goods for the military and consumer goods for the camps. They worked off the camps in seasonal agricultural production. They faced degrading and humiliating conditions, substandard sanitation, cramped living quarters, and periodic food shortages. When people got too close to the perimeter of the camps, they were reminded by the bullets of the guards that the camps were indeed prisons.

However, not everyone accepted these conditions in silence. In the camps there were important rebellions and strikes against food shortages and degrading treatment, and the military was called in to “restore order” and even shoot people. Resisting relocation, Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old from Oakland, California, refused to leave his home. While ultimately unsuccessful, he attempted to challenge the internment legally, in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court.

Internment was supported by most of the U.S. population. A poll in March 1942 found that only 1% of the respondents opposed the internment of Japanese immigrants and 25% opposed the internment of U.S. citizens of Japanese origin. The minority of people who opposed any internment included members of African American groups, Jewish American groups, religious communities, and civil libertarians. Shamefully, the largest organization of the left at that time, the U.S. Communist Party, supported the internment of Japanese Americans, which was in line with its perspective that the U.S. working class needed to line up uncritically behind the U.S. government in order to defeat fascism.

Though the Supreme Court sided against Korematsu in December 1944, another Supreme Court decision, “Ex parte Mitsuye Endo,” stated that loyal citizens could not be held without cause. This began the process of officially ending the policy of internment. During this time, people were given a train ticket back to their original homes and only $25 to rebuild the lives that had been stolen from them.

Decades later, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and other struggles of the 1960s, members of the Japanese American community began to demand “redress” (an official apology from the U.S. government) and financial compensation for people who had been detained. After years of campaigning, they pressured the Reagan administration to pass the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally condemned internment and offered $20,000 to anyone who had been interned.

More recently, survivors of Japanese internment have been at the forefront among those who have denounced the bipartisan detention of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. They remind us that the ugly history of racism and detention, and the struggle for basic human dignity, are far from over.