The six-week strike by the United Automobile Workers (UAW) against Ford, General Motors and Stellantis wound down the weekend of October 25 with the announcement that the union had agreed on a new contract with Ford Motor Company. The UAW announced agreements with the other two companies a few days later. As soon as the UAW announced tentative agreements, it directed all strikers to return to work. Members are now voting on the contracts. The early vote totals indicate the members will ratify the new contracts. The UAW website provides the full text of how the new contract differs from the ones that expired on September 14.

UAW leaders said the union’s goals included big raises to catch up with inflation, and winning a contract provision for cost-of-living raises during the 54-month life of the new contracts. UAW members are especially concerned about the security of their jobs now that their employers are beginning to build plants to manufacture battery-powered cars and trucks. Newly built plants are not automatically covered by existing union agreements for workers at the already established plants where the union is recognized. The auto companies are keen on taking advantage of this transition to impose wages and benefits far below union standards. Unionized auto workers and the UAW itself face an existential crisis given how non-union companies like Toyota produce 60% of new vehicles sold in the U.S. Non-union Tesla is even more dominant in the market for electrically powered vehicles.

The new UAW contracts provide an immediate 11% wage increase for all assembly line and other production workers already at top pay of $32/hr. Many workers earning less than top pay will receive proportionately larger increases. The old contract had two different pay and benefit schedules (“two tiers”), one for workers hired before 2007 and a lower one for workers hired after 2007. All production workers with at least four years of seniority will earn the same hourly wage by the end of the contract. The new contract provides annual “cost of living” wage increases based on inflation. By the time the contracts expire in 2028, the union estimates top pay, including adjustments for inflation, will be $42/hr. for production workers.

These pay raises do not fully compensate for how much buying power UAW workers have lost since the UAW agreed to big wage concessions in 2007. The new contracts do not eliminate the discrepancy in benefits between workers with higher seniority and those with less. In particular, pension levels were not much improved and do not even begin to catch up with the inflation of the past few years. The new contracts do nothing to stop the companies from imposing involuntary overtime; the bosses compel autoworkers to work six-day weeks for months at a time. The auto companies agreed to put some, but not all. of the new battery plants under the union contract. The bosses of course plan to build the new plants in parts of the U.S. where unions have had difficulties winning a majority of workers, which is a prerequisite for unions to bargain contracts. The union did win the right to strike over future plant closings. Stellantis agreed to re-open a plant closed this spring and rehire the laid-off workers.

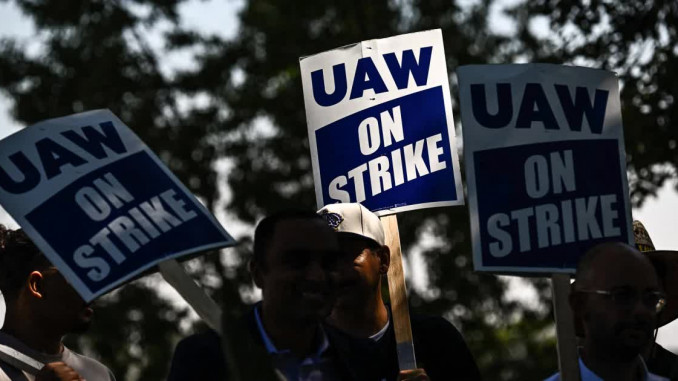

Autoworkers made it clear they had big expectations, and the contracts contain real gains, if very insufficient compared with all that autoworkers lost during the past decades of concessions granted by the UAW. The UAW’s strike strategy of declaring a strike simultaneously against all three of the Detroit-based companies but only striking a handful of plants was something it had never tried before. Many workers thought all the plants should be struck from the beginning. At the beginning of the strike, the union shut down only three assembly plants with 13,000 workers out of the approximately 150,000 UAW members who work for the three auto companies. Over the next six weeks, the UAW shut down additional plants, calling out another 37,000 workers. The union’s tactics made it even harder than in the past for rank-and-file workers to have much say over how the strike was conducted.

While the top-down way the UAW organized the strike is nothing new, the widely noted “class struggle” rhetoric of newly elected union president Shawn Fain stunned corporate America and was welcomed by most members. Fain repeatedly condemned the UAW’s decades-old policies of making concessions to the auto companies’ drive to increase profits. He said the UAW had acted like a “company union” (a union controlled by the company itself) and had allowed the auto bosses to conduct a “one-sided class war” against the members, implying those days were over.

The conduct of the strike and its results show how far the UAW is from leading its members in a struggle that unleashes the power of a mobilized working class. Rank-and-file union members will have to organize and innovate the class struggle strategies and tactics needed to successfully take on an industry re-shaping production as it transitions to vehicles with electric power. The gap between President Fain’s “class struggle” words and the union’s actual practices suggests that he could be part of the problem, not the solution.