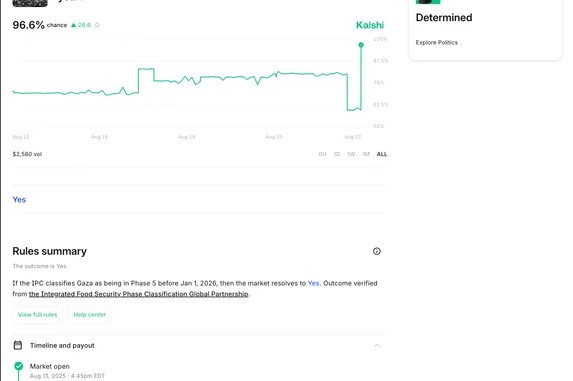

Early this month, CNN reportedly formed a partnership with Kalshi, “the world’s largest prediction market company” according to Axios. As part of the deal, CNN will embed data from Kalshi’s online market into live news broadcasts, “includ[ing] prediction market content related to politics, news, culture and weather.” Kalshi, alongside their main major competitor Polymarket, offers a marketplace in which users can trade financial options deals, in which two parties buy contracts assuming either side of a potential outcome in a particular scenario. The platforms allow you to trade on outcomes for a wide variety of events. For example, you could buy a “contract” saying you think that it will rain in New York City tomorrow; several months ago you could have bought contracts on whether or not the IPC would declare a famine in Gaza (pictured above). A “Yes” contract was priced around 75 cents in mid-August, reflecting the market’s relative certainty that a famine would be declared. Had you bought “Yes” contracts before the IPC’s August 22nd declaration of famine in Gaza, you would be paid a dollar for each contract bought, profiting 25 cents on each contract. Polymarket offers a similar contract titled “Gaza mass population relocation in 2025?”

Prediction market platforms like Kalshi have avoided being regulated like a gambling company by defining what they offer to users not as “bets” but “markets” shifting themselves from being regulated under gaming rules, to similar to how a stock market would be regulated. While gambling rules vary from state to state, financial regulations are relatively uniform, and have been systematically reduced since the financial crisis of the late 2000s. Prediction markets are capitalizing on this, aiming to “financialize everything” and “create a tradable asset of every difference in opinion” as put by Kalshi co-founder Luana Lopes Lara. These companies are growing at an extremely rapid rate. Kalshi launched in 2018, and has already raised billions of dollars in funding from venture capital firms like Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund. Massive financial resources are being poured into the expanding gambling industry: gambling rules have been relaxed in many states since 2018, and sports gambling alone has expanded into a $37 billion industry. This has come alongside a massive growth in gambling addiction.

What companies like Kalshi aim to do is to expand this trend to the next level, bypassing gambling regulations entirely and allowing users to bet on every potential event in an increasingly unstable world. Indeed, an AI-generated Kalshi ad sports the tagline, “The world’s gone mad, trade it.” Kalshi and companies like it are merely part of a devastatingly bleak vision of and for the future, in which regular people have no ability to affect the horrors playing out around the world, whether they be the brutal wars on the people of Gaza or Sudan, or the disastrous effects of climate change, or the increasing anxiety of a new economic downturn. The message from those at the top of this system is: No, you can’t do anything about the world falling apart. But you just might be able to make some money off of it.