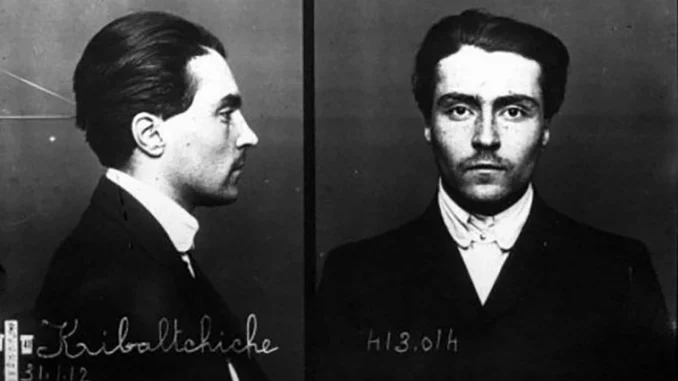

On December 30, we mark the birthday of Victor Serge, the revolutionary and writer who lived through and described in writing many of the key successes and failures of Europe’s momentous and consequential early twentieth century revolutionary movements.

Born in 1890 Brussels, Belgium, to Russian-born anti-tsarist parents, Serge (born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich) was intrigued by revolutionary ideas from early in his life. Influenced initially by the ideas of anarchism, at age fifteen Serge joined an anarchist commune, and moved to Paris, France in 1909 at age nineteen, where he taught French to Russian emigres and began writing for anarchist publications. After being sentenced to five years imprisonment for conspiracy with a gang of anarchist bandits, he was jailed in France as World War I raged, and in 1917 was released and expelled to Spain. There, he witnessed the beginnings of a general strike, where the struggle between workers and bosses was becoming acute, spilling over into outright violence on the streets. Anarchists and Socialists were both real forces within the Spanish working class, and both influenced his development during this time. Although he remained firmly committed to principles of libertarianism, Serge became drawn more to a collectivist view of how workers could win power and change the world, soon to be exemplified by the actions of the workers’ soviets (councils) and the socialist Bolshevik Party in the Russian Revolution. In the summer of 1917, he traveled through France on his way to Russia, which was in the middle of a revolutionary upsurge preceding the October Revolution. In France, Serge was once again imprisoned and held until late 1918, when, upon release, he finally entered Russia in January 1919. He greatly admired V.I. Lenin and the Bolshevik Party, and once in Russia he immediately joined the Party (which had renamed itself the Russian Communist Party), became involved with writers and activists like Maxim Gorky, and began working as a writer and translator for the Third (Communist) International, or Comintern, the body charged with leading the struggle for socialist revolution throughout the world.

While supportive of the need for force in crushing the enemies of the working class and peasants, he became discouraged by the violence of the Red Terror and the War Communism period (1918 to 1921, during the Russian Civil War). He was still a Bolshevik, but had been disillusioned by the unavoidable violence that came with revolution and its struggle against counterrevolution.

But in the succeeding years, from about 1922 until about 1928, he witnessed the tragic degeneration of the Russian Revolution and the evolution of a bureaucratic dictatorship under Joseph Stalin, who accumulated power in the years leading up to and following Lenin’s death. Driving out his political rivals one by one, creating an unattainable idea of “socialism in one country” to justify the rule of the bureaucracy, Stalin betrayed the ideals of the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik Party.

But Serge never questioned the need for socialism, and therefore did not turn away from the challenges facing the Revolution. Instead, he joined a group of Bolshevik oppositionists critical of Stalin’s leadership who organized to challenge the developing dictatorship. This group became known as the Left Opposition, with Leon Trotsky, one of the key leaders of the Russian Revolution, as its primary spokesperson. But Stalin and his bureaucratic caste had already become too powerful, and Left Oppositionists were intimidated, removed from posts, slandered in party publications, arrested, exiled, and in many cases murdered. By 1928, Trotsky was exiled, the Left Opposition was effectively silenced, and Serge, while remaining in Russia, began a time of work translating Lenin’s writings into other languages while secretly corresponding with Trotsky and other oppositionists. He was arrested by the Stalinist government on numerous occasions, and his health declined. As a writer and intellectual, Serge was well known throughout Europe, and many writers and artists petitioned for his release from detentions and, eventually, for permission to leave the Soviet Union. In 1936, he was allowed to leave, but in the process he was not allowed to bring his archives, and thousands of pages of his writings were lost.

In poor health, from 1936 to 1940 he lived in Belgium and then France. In 1940, he moved to Mexico City, Mexico, were he lived the remainder of his life until 1947, when he died at age fifty-six. He died in poverty, which is how he had lived much of his life, which had been devoted completely to the causes of truth, knowledge, working-class revolution, and socialism.

Beyond what his personal story can teach us about the commitment and dedication necessary to struggle for revolutionary change, his many works of fiction and non-fiction provide us with vivid depictions of the history of the period, and of the potential of working and poor people when they are organized and politically militant. One of them was Year One of the Russian Revolution, written in the early 1920s but first published in 1930 in France after being banned in Russia. In this powerful polemic, he passionately defends the Russian Revolution from its detractors by explaining in great detail the nearly insurmountable challenges facing the Russian revolutionaries, and defending their actions in the face of such overwhelming obstacles. In 1937, after escaping Stalin’s Soviet Union, he published From Lenin to Stalin. In this concise, detailed book, he chronicles the degeneration of the Russian Revolution from its beginnings in 1917 to the destruction of the Spanish revolutionaries in the Spanish Civil War that began in 1936. He weaves personal experiences of repression into the larger historical chronology to paint a heartbreaking picture of the decline of the Bolshevik revolution and the rise of Stalin’s counterrevolutionary dictatorship. Serge’s novels painted vivid portraits of revolutionary struggles and betrayals. To mention only two, Birth of Our Power, published in 1931 (once again in France because it was banned in Stalin’s Soviet Union), he describes the birth of workers’ power in two revolutionary cities in 1917 – Barcelona, Spain, and Petrograd, Russia. The novel captures the idealism, the heroism, the collective consciousness and collective power of the working classes, along with the tragic struggle and suffering that came along with these momentous events. The Case of Comrade Tulayev is a novel of the 1930s, conveying not only the terror of the Stalinist purge trials, but also their reach beyond the Soviet Union.

On his birthday, December 30, let’s remember Victor Serge, a lifelong revolutionary. His life and struggles can serve as a model and an inspiration for those of us who aspire to change the world. And his writings can supply us with inspiration and much practical knowledge about the successes and failures of those who have come before us in attempting to do so.