Mexican artist Diego Rivera’s painting and mural exhibit opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) on July 16, 2022, and will end on January 3, 2023. The show features more than 150 of Rivera’s paintings, frescoes and drawings that span his career from the 1920s to the mid-1940s.

The fourth-floor exhibit is organized chronologically, but covers various themes Rivera explored throughout his career. This includes paintings of indigenous people, often criticized today for their exoticism, as well as paintings of Mexican workers and florists. The exhibit also features paintings of prominent communist politicians, pieces Rivera painted in Soviet Russia, and frescoes commissioned in North America that highlight the impacts of capitalism on the working class. His art and his politics almost always intertwined. There are also a number of video installations that transport viewers to a church, a Mexico City building façade, and a mural.

The exhibit also focuses on California, where Rivera made two trips to produce commissioned works. One of Rivera’s most renowned works, made on Treasure Island, is the Pan American Unity mural, painted in 1940. Transporting the 10-panel mural from the City College of San Francisco to the SFMOMA for this exhibit was an engineering feat! The mural can now be seen on the first floor of the museum, and is free for public viewing. However, admission to the fourth-floor gallery exhibit costs a whopping $35. How might Rivera, an advocate for workers’ rights in his lifetime, and public access to history, art and culture in general, have felt about the financial restriction to accessing his work?

Throughout much of his life, Rivera, was an active member of the Mexican Communist Party. He traveled to the former Soviet Union, although the Stalinist bureaucracy later kicked him out of the party after his criticism of the regime.

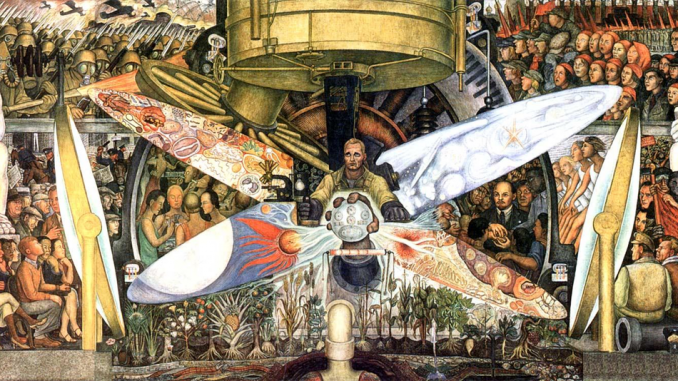

In spite of his beliefs, during his lifetime, he was commissioned and paid by some of the biggest capitalists of North America to paint murals in their banks, museums, and even their office buildings. How could a renowned Communist be revered by the mega capitalists of North America? His artwork included depictions of the marvels that were actually achieved under capitalist production, and he was able to interlace some of his socialist ideals into his works., Because of his socialist ideas, evident in many works, some of his pieces were criticized in their day and created scandals, such as the Man at the Crossroads, commissioned by the Rockefeller family, and criticized by New York City media. The mural was later torn down because it starkly highlighted the differences between two worlds – one capitalist and one socialist, and the class conflict between two opposing forces, the capitalists and the workers. When Rivera was asked to change it, instead he added a portrait of V.I. Lenin, the Russian revolutionary who was universally despised by business owners the world over. The scandal with the Rockefeller family led to the cancellation of many other commissions planned for various cities across the United States.

In the late 1930s, Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo petitioned the Mexican government to offer refuge to the exiled Russian revolutionary leader, Leon Trotsky. In 1937 Trotsky and his wife moved into the Kahlo’s famous Blue House in the Coyoacán neighborhood of Mexico City. In this time, Rivera and Trotsky had a political falling out. They quarreled for several reasons, both political and personal, but their ideological disagreements were the main source of their dispute. Trotsky accused Rivera of succumbing to the temptation to “look for a haven in the bourgeois…public opinion.” Although Trotsky and his wife moved out of the Kahlo residence, they remained in Mexico until his assassination in 1940.

These criticisms of Diego Rivera’s political perspective and artistic and personal behavior are all valid critiques of a public figure. However, it is also important to recognize the value of Diego Rivera’s artwork, and how he put working-class people at center stage. Throughout his lifetime, he was unwilling to compromise his values, and his work consistently highlighted the class conflicts inherent in capitalist society.