Labor Day is a holiday in the United States that supposedly celebrates the achievements and history of working people. Some politicians and union officials may give speeches celebrating the efforts of the nation’s working people. There will probably be some “Labor Day” sales that encourage consumerism rather than worker power. But for the working class in the U.S. and throughout the world, it may not seem like there is much to celebrate right now.

The health crisis created by the failure to respond to COVID-19 is again surging, with 628,000 dead in the U.S., and 4.4 million dead worldwide. The millions thrown out of work by the economic crisis has been accelerated and extended by the pandemic, with many still facing hardships and threats of eviction in the coming months. For those who have jobs, Labor Day may mean a day off to relax and try to forget about how crazy the past two years have been, while others will still need to work or volunteer for overtime just to pay the bills. At the same time, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and other billionaires are growing wealthier and wealthier, while the workers who create their wealth continue to struggle. A new study even finds that corporate CEOs now “earn” on average 351 times their average workers.

Despite these hardships and challenges, Labor Day is a good time to remind ourselves that our world doesn’t have to be this way, and that we can do something to change it! We may not have been taught this in school, but the working class has a rich tradition of struggling against the challenges it has faced in each generation. Labor Day can remind us that we should take the time to learn our history and take inspiration from it.

The Battle of Blair Mountain

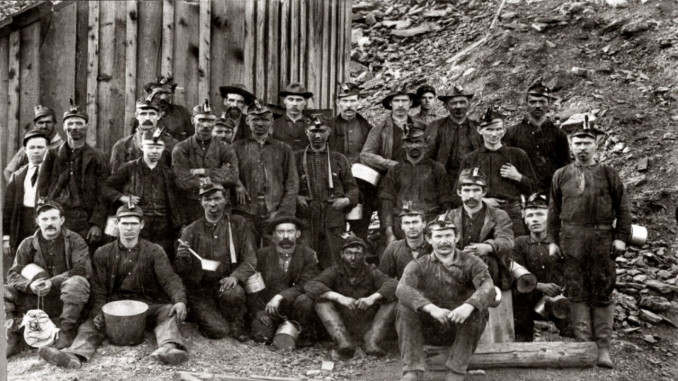

One struggle we can learn from is the struggle of coal miners that led to the “Battle of Blair Mountain” 100 years ago in West Virginia. To help understand the heroic nature of their struggle, it’s important to understand what life was like in the coal fields of West Virginia in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

West Virginia was one of the coal mining capitals of the world at this time, as massive investments in coal production were made in this region during the American Industrial Revolution. All aspects of life in West Virginia were run by coal barons. They owned all the mines, most of the land, and controlled the politicians who ran the state. They used the forces of the government and private armies to enforce the brutal exploitation of workers.

Because the mine owners owned most of the land near the mines, they had a monopoly in the region. If miners were going to work in the coalfields, they and their families were forced to live in company towns near the mines. Miners had to rent their houses, buy their food, and buy the coal that they had mined to heat their houses from the bosses who got rich from their back-breaking and dangerous work. In fact, bosses did not even pay miners with real money. They paid them in credits – called “company scrip” – that could only be used to buy life’s necessities from the bosses’ stores.

Many ended the month with nothing left. Others went into debt to the coal companies because payments for rent and food didn’t stop when the coal bosses reduced workers’ hours or closed the mines for a while. In addition to this, there were no safety measures in place. Many died in the mines in industrial accidents. Others died of “black lung” disease from inhaling coal dust all day. The disease was caused by coal particles building up in the lungs of miners. It slowly turned their lungs black, eventually forcing them to stop working. Because of this, for many, years of working in the mines was like dying a slow death.

Workers could be fired at any time, and when they were hired, they had to sign contracts saying they wouldn’t try to organize or unionize. Those that tried to organize were fired, intimidated with violence, or sometimes killed.

Facing these conditions, miners began to struggle and organize themselves in mines across coal country. They organized militant strikes to improve their conditions, and some miners fought for the right to union representation and collective bargaining through the United Mine Workers Union, founded in 1890. Strikes and efforts to organize were often brutally repressed. West Virginia often saw periods of open class warfare, with several armed confrontations taking place between striking miners trying to improve their conditions on one side, and on the other, either private armies funded by the coal bosses, or forces of the state seeking to support the bosses. Because of this, the series of struggles that took place in the period between 1912-1921 are known as the “West Virginia Mine Wars.”

The 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain was the most dramatic and heroic of these struggles, and remains the largest armed uprising of the working class in U.S. history.

A combination of events led to this uprising. In the spring of 1920, private goons hired by the coal companies were sent in to break a strike of coal miners in Matewan, a town in the southwestern part of West Virginia. One of their tactics to break the strike was to forcibly evict miners and their families from their homes in the company towns, leaving them homeless. The local sheriff in Matewan at the time, Sid Hatfield, was supportive of the miner’s struggle and did not believe the private armies had any business evicting the miners. After confronting them, Hatfield and a group of miners got into a gun battle with the private goons, killing several of them.

This event boosted the spirits of miners, as it proved that people could stand up against the coal goons. In the aftermath of this event, coal bosses conspired with the state government to capture Hatfield and workers who participated in the gunfight and try them for murder.

Hatfield was charged with murder but was acquitted, which further infuriated the coal bosses. After this, the bosses worked with the state to frame Hatfield with a bogus charge that he tried to destroy mine property. As Hatfield arrived at court to contest this charge, he was shot dead in front of the courthouse by private goons paid by the bosses. Hatfield was seen as a hero and a symbol for the miners that it was possible to fight back. For the miners, his murder was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Fed up with this murder and the continued repression of their organizing efforts, at least 10,000 miners – many veterans of World War I – organized to march from Charleston, the capital of West Virginia, into the southwestern coal fields to support the miners in their fight against the coal bosses in this region. After starting the march, miners commandeered multiple freight trains to help transport miners and to help strengthen their forces, since they knew that they would be met with violence.

The march was met by a private army of 3,000 goons funded and organized by the coal barons who set up heavy weaponry and machine guns on the strategic high ground of nearby Blair Mountain. The goons chose this spot to confront the miners because they knew the miners would be vulnerable on this part of their march route. The private army’s goal was to stop them at all costs, and they were given orders to shoot to kill any miners who dared continue.

From August 25 to September 2, 1921, open class warfare broke out on Blair Mountain. In the course of the battle, the federal government showed which class it exists to defend by sending 17,000 military and National Guard troops to reinforce the private army and militarily defeat the miners. During the fighting, the U.S. military also collaborated with the coal bosses to drop poison gas and bombs (like those used during World War I) on the fighting miners.

Since some miners were veterans and did not want to fire on other federal troops, while also realizing they could not defeat the forces arrayed against them, the miners retreated. Knowing the government would likely find them and confiscate their weapons, many miners hid their weapons and ammunition near Blair Mountain to be used for fights to come. Historians and archaeologists in the region still find weapons and ammunition on the mountain to this day. After the dust settled, dozens of miners had been killed, as well as dozens from the private militias and army. In the years that followed, hundreds of miners that participated in the rebellion were arrested and some were convicted of murder or treason.

This relatively unknown piece of worker’s history shows the heroic efforts miners took to defend themselves and challenge their exploitation. It also shows the brutal repression the bosses and government will carry out to maintain their system of exploitation.

Lessons for Today

To this day, traditions and stories like these live on in miners’ families. On Labor Day, we should remember the importance of learning and transmitting the rich history of the working class to the next generation, because it is our history, too.

We can learn from the miners and others who came before us, who relied on their own forces and determination to stand against the oppression they faced. In doing so, we can begin to imagine mobilizing our collective power in the face of a global pandemic, an economic crisis, brutal systemic racism, and a looming environmental catastrophe. In doing so, we can begin to think about the prospects we have to determine our own future.