Early in the morning of Monday, December 5, 1955, the buses of Montgomery, Alabama began their routes, expecting to pick up and carry tens of thousands of commuters to the first workday of the week. But as the routes continued throughout the morning, it became clear that the buses would not fill up. The entire Black population of Montgomery was staying off the buses, beginning the Montgomery Bus Boycott. It would last 382 days, and bring both the city of Montgomery and the bus companies to their knees in the face of the sustained, well- organized refusal to ride.

This concerted action was years in the making. Aside from the indignities of segregation in most public places and workplaces, Black people were treated just as badly on buses, being forced to sit in the back and enter only through the back door, being forced to defer to white passengers and drivers, and occasionally being arrested or even shot if perceived as unruly or disrespectful. Earlier in 1955, a fifteen-year-old Black girl, Claudette Colvin, had been arrested for refusing to budge on orders from a bus driver. On December 1, Rosa Parks was famously arrested for the same reason.

Parks had not planned to resist a drivers’ orders, or to get arrested and become a symbol for resistance to Jim Crow, on that particular day. But she also didn’t just have tired feet from a long day’s work, prompting her to spontaneously sit down. Parks, like most Black people, had hated the Jim Crow segregation for her entire life. She had been an active member of the local chapter of the NAACP for ten years, had attended the now famous Highlander Folk School, had been active with local labor leaders like E.D. Dixon of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and knew she could expect support from the Women’s Political Council (WPC), which one historian has called “the most militant and uncompromising voice” of Black Montgomerians in this period.

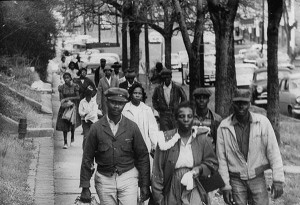

In the coming days, these people and organizations joined with local Black pastors to call for a one-day bus boycott on Monday, December 5, the same day Parks was to appear in court to defend herself against the charges from the arrest days earlier. They began a brief campaign to promote the boycott, and word spread quickly. As Parks and other organizers of the boycott walked toward the courthouse that Monday morning, they realized that the buses were nearly empty, and that they saw few or no Black passengers. In these early minutes of the boycott, they realized it was an initial success.

Later that day, Parks and other organizers attended a rally of fifteen thousand people at a local church, where the Rev. Martin Luther King gave his first major speech as an active leader in the movement for Black rights. At the end of the night, the participants voted to continue the boycott indefinitely, and created a new coalition, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to organize the boycott.

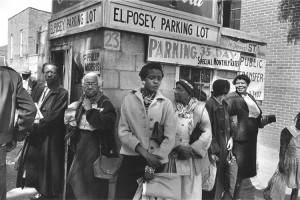

Over the next months, sustaining the boycott became a truly monumental undertaking. For the next year, the MIA spent more than $3,000 per week financing transportation. They paid twenty full time drivers, paid taxi drivers to give discounted rides, filled gas tanks, received donated cars, monitored pick up spots, and had fifteen full-time dispatchers organizing between fifteen and twenty thousand rides per day! Many simply walked, rode bicycles, and even rode horse-and-buggies. Women provided the backbone of the boycott, with the WPC leading the way. The massive undertaking was a marvel of organization and dedication.

Police harassment was the norm, with drivers and riders regularly stopped, asked for identification, and occasionally reported to their white employers, who sometimes harassed them at work and even fired them. Parks was fired from her job, and her husband was pushed out of his. Boycotters were pelted with fruit and vegetables, splattered with urine, and otherwise harassed as they waited for rides or walked to work. E.D. Nixon, King, and other leaders who lived in houses had their homes bombed. And for months, the city was unwilling to meet even modest demands made by the MIA, which in turn increased the resolve of the boycotters. The boycott continued through the winter, through harsh weather and rain, through the summer, and into the winter again.

Finally, after one year, and given the increasing pressure of the boycott and two separate federal court rulings declaring segregation to be unconstitutional, the segregation of public transportation in Montgomery and other parts of Alabama was officially ended. Although this did not end segregation immediately or in full, the dam of Jim Crow segregation was cracking. On December 20, 1956, 382 days after the boycott began, it successfully drew to a close, having won – at least legally – the rights of Black Montgomerians to freely use public transportation on an equal footing with whites.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott often finds its way into history books and the popular consciousness as the work of two people: the tired seamstress Rosa Parks, and the inspiring preacher Martin Luther King, both of whom followed the principles of non-violent civil disobedience. But this idealization leaves out much of the most significant elements of the boycott and why it worked. (For a thorough description and analysis of Parks, the boycott, and the larger movement of which they were a part, see this excellent book.)

The boycott was successful because tens of thousands of working-class Black residents of Montgomery were sick and tired of the boot of racist oppression on their necks, exploiting them as workers and Black people. They were sick and tired of the daily indignities in their workplaces, in public spaces, and on their commutes. They were sick and tired of barely making ends meet and also being treated as if they were not human.

Significantly, however, they made up their minds to take action. While it was the act of one woman that sparked mass action, it was the collective decision of thousands first to participate in and then to continue the boycott that led to victory. It was the collective organization and determination and tenacity of tens of thousands who risked their jobs, their safety, and their very lives to stand strong and unified against racist repression.

In the face of a society designed to totally repress them, the Black people of Montgomery sustained themselves through an entire year of struggle and repression, and achieved a notable victory in the struggle for human rights. It is an example we can learn from today, as we work to build the organization and solidarity that will enable us to win the victories of the future.