The Minneapolis general strike of 1934 grew out of a strike by the local union of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) against most of the trucking companies operating in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a major distribution center for the Upper Midwest. It became one of the most important and influential struggles of the working-class response to the Great Depression.

Background to the Conflict

The Teamsters union was founded in 1903, originally for drivers of teams of horses, mules, or oxen, but had evolved into a union of truck drivers. Its members were divided into separate local unions along craft lines: ice wagon drivers in one local, produce drivers in another, milk drivers in another and so forth. All of these various local unions had their own local leadership and local methods for decision-making. But at the same time, all locals were part of the larger international union, which had its own centralized leadership that had authority above all the locals. The international union (like many unions both then and today) was cautious and resisted any use of the strike. The international union’s constitution required a two-thirds vote of a local’s membership to authorize any strike action, but at the same time gave the international union president the power to withhold strike benefits if he believed that a local union had struck prematurely.

But because their work transporting goods brought them into contact with many workers in other industries, Teamsters had often been called on to support the strikes of other workers, and had in some areas developed strong traditions of solidarity with others in the working class. The Teamsters also had some general locals, combining different crafts or industries. Local 574 in Minneapolis, which only had about 75 members at the start of 1934, was one of these.

Revolutionary Socialists (Trotskyists) in Minneapolis

In addition, several members of Local 574 were former Communist Party (CP) members who had left the CP to join the newly formed Communist League of America (Communist League), which formed in 1928 as a part of the International Left Opposition.

The Left Opposition was formed in response to the bureaucratic dictatorship that was taking shape in Russia at the time, and its primary spokesperson was Leon Trotsky, one of the key leaders of the Russian Revolution. In 1924, Joseph Stalin became the head of this new bureaucracy and betrayed most of the ideals of the Russian Revolution. While the Russian Revolution stood for the democratic mass participation of workers in leading the revolution and running the new society, Stalin came to represent the interests of a bureaucratic clique that took control over the new Soviet government, which suppressed democracy and pushed any of Stalin’s political rivals out of the Communist Party. In addition, Stalin completely betrayed the politics of international workers’ solidarity that were central to the revolution, and instead replaced them with a new type of Russian nationalism, captured in the ridiculous policy of building “socialism in one country.”

The Left Opposition was formed specifically to oppose this rightwing turn that was happening under Stalin. But ultimately Stalin and his bureaucratic clique had become too powerful, and Left Oppositionists were intimidated, removed from posts, slandered in party publications, arrested, exiled, and in many cases murdered. In 1929, Stalin’s dictatorship exiled Trotsky from Russia.

In the United States, as in many other countries, militants who supported the Left Opposition were often kicked out of the Communist Party, and had to form their own organizations, which was the case of the Communist League in 1928. By 1933, it had about 40 members in Minneapolis, which allowed them to play an important role in the strike.

Two Strikes Lead to a General Strike

These worker militants began by organizing coal drivers during a strike in early February 1934. This strike ignored both the cumbersome approval procedures established under the Teamster international’s constitution and the ineffective mediation procedures offered under the newly enacted National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933.

The Communist League militants played essential roles in organizing the strike. Their organizing meetings made possible strongly aggressive picket lines and came up with the idea of “cruising picket squads” that could move around town wherever they were needed. This strategy helped the strikers close 65 truck yards and 150 coal offices in the first three hours of the strike. The employers caved in after three days, and agreed to a union contract and increased pay.

This victory gave Local 574 an unprecedented boost in membership and credibility among drivers and warehouse workers, and by April its membership rose to 3,000. By May, the number of organized drivers and warehouse workers in Minneapolis had grown to 5,000 and preparations were made for a drivers’ and warehouse workers’ strike, as many companies in the city refused to recognize and bargain with the union.

The union prepared in advance for the strike. It rented a hall for a strike headquarters. The workers elected a strike committee to make strategic decisions about strike policy, and that committee grew to 100 members during the strike.

The strike began on May 15 after the employers refused to talk with the union. The workers held a mass meeting of drivers and warehouse workers in a large, block-long garage that would become the operational headquarters. From there, they sent out pickets across the city, focusing on mass picketing at strategic points. Flying squadrons (the cruising picket squads developed during the coal strike) drove around to identify locations that needed pickets.

Every evening they held a “general assembly” at the strike headquarters open to all strikers and supporters. At the general assemblies, workers could get reports on the day’s activities, have discussions with each other, and also had guest speakers and entertainment. This built both a sense of community and confidence in the work of organizing.

This garage headquarters had offices, food service, and medical areas. The space was maintained by two 12-hour shifts serving food to at least 4,000 people daily. It was a place for workers to eat and meet and talk. Volunteer doctors and lawyers and related personnel also served the strikers in the garage.

Starting in June, they published a weekly and then a daily newspaper to keep workers and the public up-to-date on what was going on from the workers’ point of view, challenging the perspective of the bosses’ daily newspapers. Ten thousand copies were distributed daily at no charge, though donations were accepted.

It wasn’t striking workers alone that made the strike effective. At the time, there were about 30,000 unemployed in the city, nearly one-third of the workforce. Many of them were organized for mutual aid and to fight for relief. The Teamsters supported the call for more public relief for the unemployed and many unemployed workers got involved in the strike as pickets and organizers.

Women were active in the strike, along with both family and friends of strikers from across the city. The prevailing culture of gender oppression largely confined women to work that included office work, food preparation, and medical care. But some women drove trucks carrying pickets from place to place, and a demonstration of 700 women marched on the mayor’s office to demand the withdrawal of recently deputized special police.

In the first weeks, the strike was remarkably effective, shutting down most commercial transport in the city, particularly the market area where large quantities of goods were brought to warehouses, stored, and loaded onto trucks for shipment to smaller retailers. To avoid shortages for the larger population of the city, the strike committee exempted certain farmers who were allowed to bring their produce into town and deliver it directly to grocers.

The Struggle Against the Bosses and the Government

The market area was the scene of the fiercest fighting during the early part of the strike. On May 19, Minneapolis Police and private guards beat a number of strikers who were trying to prevent strikebreakers from unloading a truck in that area. The cops also detained several strikers who had responded to a report that scab drivers were unloading newsprint at the two major dailies’ loading docks. When those injured strikers were brought back to the strike headquarters, the police followed. The strikers, however, not only refused to let the police into the headquarters but, in the confrontation out front, left two police unconscious on the sidewalk.

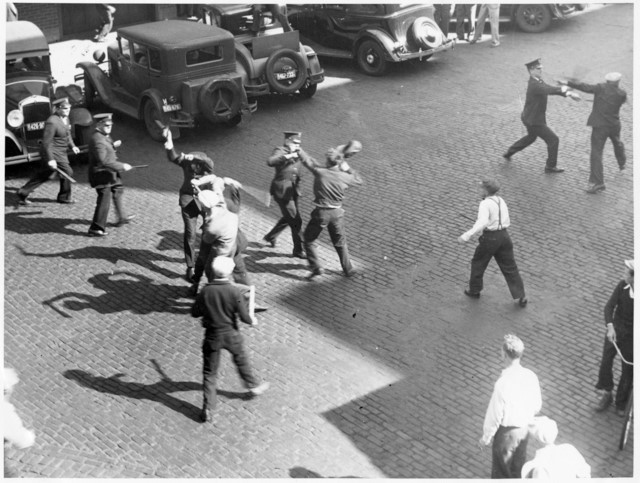

Fighting intensified on May 21 when the police, reinforced by several hundred newly deputized members of the Citizens Alliance (an organization on the side of the bosses whose primary aim was to break strikes and bust up union organizing efforts) attempted to open up the market for trucking. The battle became a general brawl when hundreds of workers armed with clubs of all sorts rushed to the area to support the pickets. When the police drew their guns, the union sent a truck loaded with pickets into the mass of police and deputies in order to make it impossible for them to fire at them without shooting at each other.

Other unions, particularly in the building trades, struck in sympathy with the Teamsters. On May 22, the picketers took the offensive and succeeded in driving both police and deputies from the market and the area around the union’s headquarters. Of the several hundred deputized “special police,” two were killed. In the following large clashes, another roughly two dozen special police, municipal police, and strikers were beaten or wounded.

The Central Labor Council, the Building Trades Council and the Teamsters Joint Council approached the Minneapolis Chief of Police to propose a truce, under which the local would cease picketing for twenty-four hours if the police and the employers ceased trying to move trucks. The employers, the Teamsters and the building trades signed an agreement, but when the Chief declared that the police would move trucks once the truce expired, the union announced that it would resume picketing.

At this point the city government appealed for Governor Olson (a member of the Farmer-Labor Party, which was supposedly sympathetic to workers) to mobilize the National Guard. Olson did, but stopped short of actually deploying them, being unwilling to alienate his labor supporters. Olson had already been attempting to mediate the dispute, and on May 25, the employers and the union reached an agreement on a contract that provided union recognition, reinstatement for all strikers, seniority, wage arbitration, and a “no-discrimination against strikers” clause. The membership approved it overwhelmingly and business temporarily resumed.

But the bosses weren’t done yet. The union thought that the employers agreed to include the “inside workers” – that is, the warehouse employees – as well as the drivers and loaders in the contract. But the employers broke their word on that agreement, and the strike resumed on July 17. The governor again mobilized, but did not deploy, the National Guard.

It was clear that for this strike, the state government – now with the tacit support of a federal mediator – was looking for any excuse to use large-scale force against the workers. Additionally, police were more heavily armed than in the first round of the conflict, and the International Teamster leadership was now openly attacking Local 574. So the local union’s leadership chose to use different tactics. To avoid being accused of initiating any violence, the newly elected 100-member strike committee told its members to picket without carrying clubs or weapons of any sort. This policy change wasn’t a question of cowardice on the part of the union and the workers. They were up against even more powerful forces now. Some of the local unions that had supported them in the past had not yet joined in this second strike, and they were not sure they had the forces available to effectively defend themselves against more violent attacks. They therefore made a strategic decision to do everything possible to avoid open confrontations with the police.

After a few days of picketing which stopped at least one attempt by the bosses to move loaded trucks into the market area, on July 20, a single truck drove to the central market escorted by fifty armed policemen. The truck made its small delivery successfully, but then a vehicle filled with pickets cut off the truck. Although a commission later found that the workers had been unarmed and no threat to the police, the police opened fire on the vehicle with shotguns, then turned their guns on the strikers who were filling the surrounding streets. Two strikers died and sixty more were badly wounded in what became known as “Bloody Friday.”

The police violence against unarmed workers sparked a show of support from other unions, including a one-day strike by some of them, and on July 24, 40,000 workers marched through the streets during the funeral of Henry Ness, one of the murdered strikers. The local union continued to urge its members not to give the police any justification for further attacks, and actually disarmed a number of picketers who wanted to return fire with fire. Local 574 also chose not to overtly attempt to stop delivery trucks, which were accompanied by convoys of forty police cars apiece. They instead sent so many cars with pickets to accompany those convoys that the streets were effectively clogged and the police were never able to shepherd more than a few delivery trucks on any given day.

Then, on July 26, amid the deaths of pickets at the hands of the police, Farmer-Labor Governor Olson declared martial law and mobilized four thousand National Guard troops. The National Guard began issuing operating permits to truck drivers and engaging in roving patrols, curfews, and security details. On August 1, National Guard troops seized the strike headquarters, arrested union leaders, and placed them in a stockade at the state fairgrounds in Saint Paul.

Hard-Earned Victory

Although the strike was gravely weakened by this open state repression and by the economic pressure felt by the strikers on a daily basis, it continued into late August. By continuing to withhold their labor, the union and its supporters made it impossible to resume business as usual in and around Minneapolis.

A little less than one month later, on August 21, a federal mediator got acceptance of a settlement proposal from the head of the Citizens Alliance, incorporating the union’s major demands. The settlement was ratified by the workers, breaking the back of employer resistance to unionization in Minneapolis. The workers and the community around them had held out and won.

The strike changed Minneapolis. In the years before 1934, it had been an open-shop town, completely under the control of the Citizens Alliance. After the strike, thousands of truck and warehouse workers joined the Teamsters, and thousands of other workers organized their own unions with the assistance of Local 574. Many workers could now work and live without fear of starvation and oppression in the workplace.

The strike also gave the Communist League a strong position in the local, and in other Teamster locals in the Minneapolis region. The League grew to over 100 members. Through the unions they led, the Trotskyists won leadership roles within the city’s Central Labor Council, helping to organize the first area-wide contract for any union outside of rail. The Trotskyists established locals of their party wherever there were Teamster locals, from South Dakota to Iowa to Colorado.

Lessons for Today

The radical democratic leadership from the Minneapolis Teamsters made them the enemy of conservative union bureaucrats throughout the nation. In 1935, International president Tobin expelled Local 574 from the IBT. In 1936, however, Tobin was forced to relent and recharter the local as 544.

Local 544 remained under revolutionary socialist leadership until 1941, when eighteen leaders of the union and the Socialist Workers Party (successor to the Communist League) were sentenced to federal prison, the first victims of the anti-radical Smith Act. At this point, Tobin was able to impose a trusteeship on the local and take over its leadership with help from the government.

This repression – by union leadership in concert with the capitalist state – left the door open for the process of bureaucratization in the Teamsters union.

Nevertheless, the history of the Minneapolis General Strike holds lessons which are applicable today.

One important lesson is that revolutionary workers can gain the confidence of many of their peers by being honest and effective leaders in workers’ struggles, even if those situations are not revolutionary. Revolutionaries’ knowledge of history means not always starting from scratch, as we can draw on past examples to shape our responses to today’s challenges. This is what made the Minneapolis leadership so effective in 1934. Even though most Minneapolis workers did not join the Communist League, they gained a respect and trust for its militants that made it possible for those militants to discuss all kinds of political ideas with a broad range of workers, extending a revolutionary analysis of capitalism as well as a revolutionary approach to class-struggle organizing to a broader layer of workers.

Another lesson is that the struggle of any particular group of workers, in this case the Teamsters, can be an opportunity to engage the working class more broadly. This can be done by organizing with the unemployed and with workers in other industries in order to reinforce feelings of a common interest on a class basis, as well as the idea that class solidarity is essential to workers’ success in the struggle – “an injury to one is an injury to all.” The process for doing this means developing the organizing and leadership skills of as many workers and supporters as possible.

Another lesson is that it is possible to organize and win a militant fight, even in a union with a reactionary leadership at the top. The workers chose their local leadership themselves democratically, over the objections of Tobin and the international union, and organized everything themselves, from flying squadrons to a daily newspaper to food preparation and medical care, from the bottom up. And when they relied on their own ideas, their own solidarity, and their own power, they won.

The Minneapolis General Strike of 1934 was a shining example of the organizing potential of the working class.