January 8-10 marks the anniversary of the Louisiana Rebellion of 1811, also known as the German Coast Uprising. At the time, it was the largest slave insurgency in the history of the United States, involving between 200-500 slaves fighting for their freedom. It is sometimes referred to as “America’s First Freedom March.”

It didn’t matter that some had spent their entire lives in Louisiana and others had recently been torn away from West Africa. It didn’t matter that they had come from differing tribal affiliations. It didn’t matter that some spoke only French Creole and others only English, and others only spoke regional dialects from West Africa. They were able to speak a common language of revolt.

At the time of the revolt, even though the region along the Mississippi River was known as the German Coast because of the sizable number of German settlers, roughly 60% of the inhabitants were enslaved people descended from Africa and then worked on sugarcane plantations.

One of the main leaders of the revolt was Charles Deslondes, who happened to have lighter skin and was a slave overseer himself – occupying a relatively privileged position compared to other slaves. Like his peers, he would treat the slaves brutally to get them to work harder and maintain work schedules. However, Deslondes despised the slave owners. Unlike his peers, rather than continuing to carry out the interests of the slave master, he became more and more convinced to fight against the system of slavery. Deslondes was at the Woodland Plantation, about 30 miles West of New Orleans. In the middleman position that he occupied, Deslondes connected with other enslaved men who could be organizers alongside him, like Kook and Quamana, recent arrivals from West Africa.

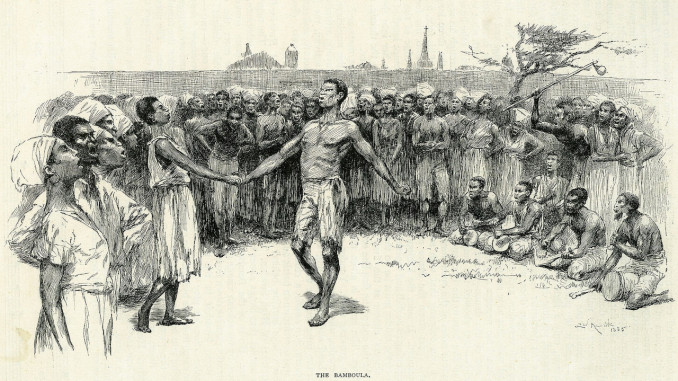

During that time period, slaves would not work on Sundays and would gather in markets to trade, play music, sing and dance. For years, organizers like Kook and Quamana used these Sunday gatherings to connect with the disparate communities dispersed across plantations, spread ideas of revolt and build a broader network for a future struggle. Forms of dance were often used for military training.

The rebellion broke out on January 8th when 15-25 men attacked the slave owner and his son at the Woodland Plantation with knives, and broke into his storage to take weapons and militia garb. The timing of the revolt was no accident, as Louisiana Governor Clayborne had just sent troops to Baton Rouge to secure the annexation of Spanish West Florida, leaving New Orleans practically defenseless. The rebels marched down the Mississippi River towards New Orleans, from plantation to plantation, attacking slave owners and freeing the slaves in the process. People freed from each plantation joined the insurrection as it marched and grew. The largest estimate of the size of the revolt put their total number at 500. Their action was highly organized and intended to eventually enter New Orleans to demand that the governor abolish slavery in Louisiana. They were freeing slaves and destroying plantations along the way. They passed through and liberated some 10 plantations in the process.

However, they ultimately did not have the arms or ammunition to finish their plan, and did not make it to New Orleans. News of the revolt had made it to the governor. Within two days of the revolt, volunteer militiamen of landowners and planters outflanked them. The governor was in no mood to negotiate. They were met with extreme brutality, tried in a kangaroo court just to have their bodies dismembered and put on display to strike terror in the rest of the enslaved population. Heads of murdered rebels were put on stakes at the gates of the various plantations and levees for everyone to see. By the end of January, nearly one hundred heads were displayed on the levee to make a statement – challenges to their power would have consequences.

In the aftermath, brutality, control and surveillance were escalated against the slave population. The Sunday afternoon gatherings were shut down. A month later, the governor wrote to Washington requesting a permanent military presence so that nothing similar could ever get out of hand again. Soon after, Louisiana was officially admitted into the larger United States by the federal government, recognizing it as a slave state. New Orleans grew to be the most important port in the South as well as one of the biggest markets for the slave trade.

It is worth nothing that the revolt took place in the aftermath following the Haitian revolution of 1791-1804, the only successful revolution led by slaves in history, and one that fought off the French, Spanish and British Empires to become the first free Black republic in the entire world. The Haitian Revolution had an enormous impact throughout the world, and the Southern United States in particular, by arousing the rebellious sentiments of millions of enslaved people. In addition, refugees from the Haitian conflict came into the Louisiana region and brought their traditions and spirit of struggle. While it has never been confirmed, some speculate that Charles Deslondes himself originally came from Haiti.

In the final analysis, the slave revolt was not successful in leading to a life of freedom for its participants or smashing the cruel and dehumanizing institution of slavery. To do that required a social revolution against the plantation owning class of the South. The people who participated in the revolt knew that their outcome could be death. Despite its failure, it must be remembered that the revolt, like many before and after it, was an indication of the growing resistance among slaves in the U.S. and set the stage for the coming struggle against chattel slavery that took place during the Civil War, in which hundreds of thousands of Black people fought for their freedom.

In the same way that the spirit and history of struggle passed through the Haitian Revolution, through the Louisiana Rebellion of 1811, through the Civil War, it also passed through the Civil Rights Movement and Black Lives Matter movement. For all of us, Black or otherwise, we can take inspiration from the courageous struggles of the past and stand on the shoulders of those before us who fought for freedom and dignity.