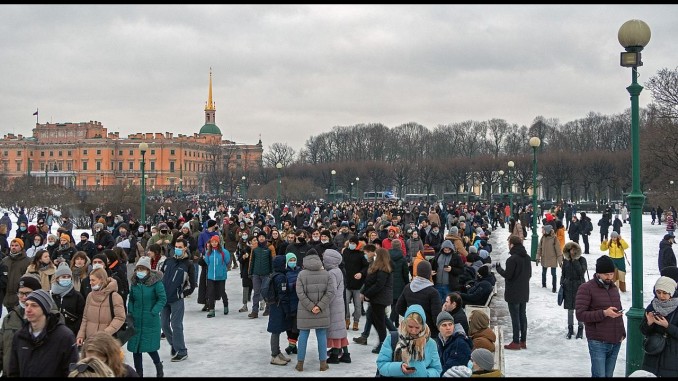

The Russian regime of Vladimir Putin has remained in power for twenty years. While the Russian state holds elections and pretends to be democratic, Vladimir Putin has ruled whether as president or from the behind the scenes, directing politicians he controls. But now, many Russians have had enough. They’ve rallied around the imprisoned opposition candidate Alexei Navalny. With thousands of Russian people in the streets in over a hundred major Russian cities, the protests are the biggest since Putin took power.

Putin is used to holding on to power by force. He was once a part of the KGB – the secret police of the USSR. Putin used what he learned as a police agent in the old Russia to become the ruler of the new Russia. Putin’s career has been accompanied by the intimidation, injury, and assassination of political opponents. Putin’s main goal has been to protect and represent the interests of the “oligarchs,” the wealthy Russian businessmen who have used the collapse of the USSR to enrich themselves. At the same time, he promised stability to an older generation, exhausted by the collapse of the USSR and the chaos that followed.

Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader, is a young capitalist who grew up in Putin’s Russia. He made his money in gas and oil. This experience pushed him to enter the political scene as a commentator on corruption – showing how Putin-connected businesses were stealing state funds on oil development projects. His success as an anti-corruption campaigner led to his political career. In 2016, Navalny announced his entry into the 2018 presidential elections. His campaign was accompanied by anti-corruption rallies and protests across Russia.

After announcing his candidacy, Navalny was physically attacked and persecuted by the Russian regime. His presidential candidacy was barred by the Russian state and Navalny was not allowed to run. But he remained an important public figure, criticizing constitutional amendments passed in 2020 that guaranteed Putin would rule Russia for life. This January, a chemical attack put Navalny in the hospital in Germany and, upon his return to Russia, he was imprisoned. These attacks sparked the latest wave of ongoing protests.

While Navalny objects to Putin and his friends’ anti-democratic manipulation of politics, he is hardly a radical. Navalny calls himself a nationalist and has used anti-immigrant rhetoric in his campaigns. He supported Russia’s war against Georgia in 2008 and called for ethnic Georgians to be expelled from Russia. Nevertheless, Navalny has become a positive symbol to a new generation of young Russians. They have had it with Putin and his oligarch friends. They take hope in Navalny’s opposition to Putin in the face of physical attacks, and imagine a Russia that is at least a little less corrupt. They are willing to face police repression, imprisonment, or worse to oppose Putin. If the protests continue to grow in the face of state repression, this new generation of protesters may find that they can go beyond Navalny and demand more than just Russia without Putin.