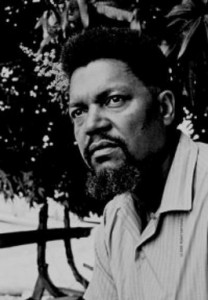

On February 26, we celebrate the birthday of Robert F. Williams, a pioneering fighter for Black rights who advocated armed Black self-defense against the racist violence of the Jim Crow south.

Rob Williams was born in 1925 in Monroe, North Carolina. Growing up he saw and experienced violent treatment of Black people on the streets of his hometown. In Detroit, where Williams went for work during World War II, he again saw white on Black violence when conflicts over affordable housing spilled over into violent, racialized rioting. He spent one year in the Marines (where he challenged discrimination by his officers), and then worked in factories in Michigan and New Jersey before returning to Monroe in 1955, where he began political organizing in the Black community. There, segregation was the legal and social norm, and the Ku Klux Klan held rallies of thousands and enforced the social order.

Williams was initially active as a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was fresh off the famous victory in the Brown v. Board of Education case that declared school segregation unconstitutional. The goal thus became to ensure that the court ruling was actually enforced and segregation actually ended. But in many places the southern NAACP had for years accommodated itself to the daily status quo of segregation, and was mostly unwilling to take on the major challenges ahead. The Monroe chapter was in such a state of decline that they were about to disband, until Williams brought his energy to the group and became president of the local chapter. He and his followers built a new type of NAACP organization, focused less on legal actions, more on member organization and activity, and more attuned to the needs of the working-class Black population in the town.

From 1957 to 1961 they integrated the public library and then the public swimming pool. Black children were not allowed in the public pool, swimming instead in the river, and when a Black child drowned, opening the pools to Black children became a priority. But after picketers were fired upon during a protest to open a local swimming pool and the police looked on without taking action, Williams became convinced that Black people needed to organize themselves for self-defense if they hoped to change their condition. In a 1959 interview after a white man was acquitted for the attempted rape of a black woman, he said:

“If the law…cannot be enforced in this social jungle called Dixie, it is time that Negroes must defend themselves even if it is necessary to resort to violence…There is no need to take the white attackers to the courts because they will be free…The federal government is not coming to the aid of people who are oppressed… If it is necessary for us to die, then we must be willing to die, and if it is necessary for us to kill, we must be willing to kill.”

After this statement, the national NAACP, heavily reliant on the financial support of white liberals, suspended him from his elected position. Rather than support this “punishment,” the local chapter elected his wife Mabel to take his place, and he continued to work hand in hand with her to organize the group, beginning with the publication of their own newspaper, The Crusader. They presented a Ten- Point program to the Monroe City Board, demanding among other things that local factories and the local government hire Blacks, that schools be desegregated, that Blacks be given full government services, and that segregation be ended throughout the entire town.

Having learned to use weapons as a daily part of rural life when he was a child and having furthered his training in the military, he organized an armed guard for Black self-defense – with an official rifle club charter from the National Rifle Association (NRA)! He and at least 50 other Black men, mostly veterans, formed the basis of this group, and were committed to defending the rights and lives of Black residents in the county. They were organized and ready to defend their community against the terrorism of the Klan, who often rode through the Black section of town in a show of force, honking their horns and firing their weapons. When they attacked the home of Albert Perry, the vice president of the Monroe NAACP, they were met with gunfire from the sand-bagged emplacements around Perry’s house, which ended their attempt to drive Perry out of town by force of arms.

But while their advocacy of gun rights is what made Williams famous, he and others always viewed guns as just tools that could only be put to good use when part of larger political organization and actions. Nonetheless, these armed, collective actions made them a threat to the entire white supremacist power structure of the rural south.

As a threat to the system, Williams and his family became the targets of constant harassment, threats, and occasional violent attacks on their home. In 1961, after controversies over guarding Freedom Riders in Monroe, and after being accused of kidnapping a white couple who needed refuge from the conflicts in town, Rob and Mabel and their two sons fled first their town and then the country. The family lived in Cuba for five years, from which they produced a radio show called Radio Free Dixie that broadcasted news, political discussion and entertainment specifically for Black Americans. After moving to China for another three years, they finally resettled in the United States in 1969, still facing kidnapping charges and possible extradition to North Carolina.

When he came back he did not seek the political spotlight (as the CIA thought he might – speculating that he might fill the void left by the deaths of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King), instead choosing to live in Western Michigan and work as an educator and local community activist. He was eventually cleared of the charges against him, and he died in 1996.

His story comes down to us primarily through his book, Negroes With Guns, first published in 1962, widely considered one of the founding documents of the Black Power movement. It preceded the Deacons for Defense and Justice, who in 1964 and 1965 acted as armed security for southern civil rights marches led by Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael, and others. And it influenced the Black Panther Party For Self Defense. It also led to a documentary of the same name in 2004, and to books like Radio Free Dixie by Tim Tyson and This Non-Violent Stuff’ll Get You Killed by Charles Cobb.

Although he never became as well-known as Malcolm X, Williams and his comrades raised many of the same questions. That is, should Black people continue to demand change completely unarmed in the face of violence from white supremacists? Or, in the face of violence intended to continue their oppression and exploitation, should Black people arm themselves and prepare to engage in collective struggle for self-defense? Robert Williams and his comrades in arms answered that question in Monroe, North Carolina:

“I advocated violent self-defense because I don’t really think you can have a defense against violent racists and terrorists unless you are prepared to meet violence with violence, and my policy was to meet violence with violence.”

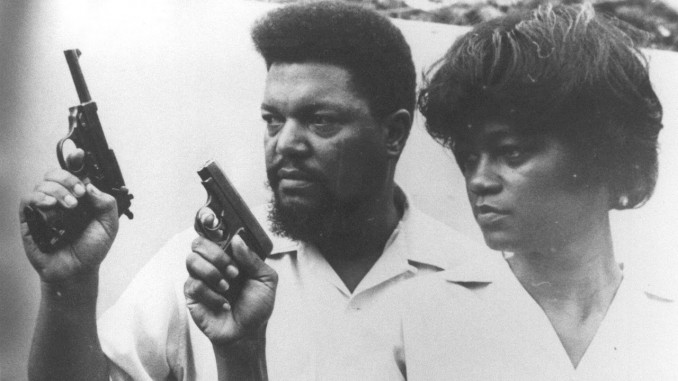

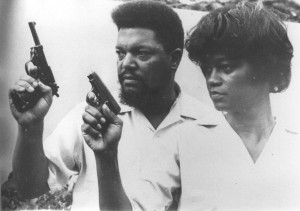

Robert and Mabel Williams (from the cover photo of Negroes With Guns)