May 18, 2021

Translated from the French in Convergences Revolutionnaires, the site of the Etincelle Fraction of the NPA

In response to a demand for a Constituent Assembly last year, Chile recently held elections to select the leaders of this new body. May 15 and 16 continued to be bad days for the Chilean bourgeoisie. Billionaire President Sebastian Piñera had to concede on Sunday night, stammering at the press briefing. The defeat is humiliating despite a record abstention of 60%. The right wing–although it was united under a single ballot–could not prevent Piñera’s defeat, even without the participation of working people and the poor that hate the president. Many historical strongholds were lost in the municipal elections, such as Maipú, Estación Central, Viña del Mar, and a number of governors were elected for the first time, especially those elected to the future Constituent Assembly. The far left militant circles were surprised by the extent of the defeat. While the left is hindered by a front that does not know what to do, the right is temporarily ruined, and independent candidates are in the spotlight. So, are we witnessing a continuation of October 2019 in Chile once again or are we entering an unprecedented situation?

Electoral lessons: a regime in crisis and new political composition

Over the past two years, there has been a social awakening in much of Latin America, including the current explosion of activity in Colombia. In Chile, several factors open up many possibilities.

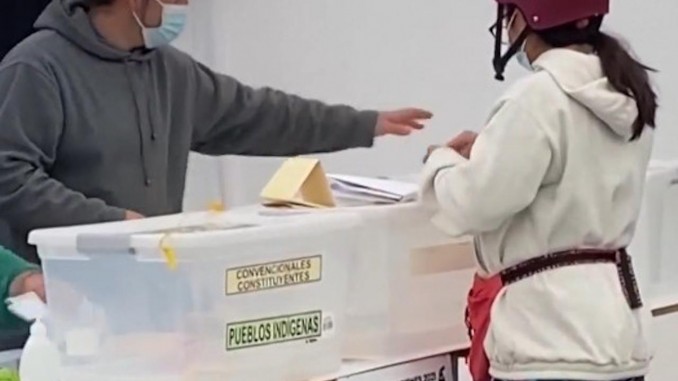

The first and most obvious is the crisis of the regime that came out of the democratic transition. The legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990) is now fully hated as was shown by last year’s massive rejection, which demanded the creation of a Constituent Assembly, equally divided between men and women (a world first) and with 17 seats out of 155 reserved for native peoples–a Chilean first (this representation was received as a step forward by the Mapuche communities in particular, but greatly underestimates the Indian component of Chile. (A city like Santiago has a population of Mapuche origin well over 30%).

Due to its strong finish in the most recent Congressional elections, in which they won 39% of the votes, the right and extreme right coalition expected to easily exceed the one-third threshold that would allow them veto power. The surprising results, however, showed that not only the right-wing coalition but also the coalition of moderate and center left parties led by the Socialist Party failed to exceed this crucial proportion of seats. More importantly, the supposed radical left no longer has excuses not to propose the real reforms they brought up during the campaign: the issue of the commons has been put forward (waterways are private in Chile), but also pensions, health, access to education or even the release of political prisoners, among others.

Independent candidates

The second factor is the temporary fragmentation of political forces because of the emergence of independent candidates. Welcomed by leftist commentators, these candidacies certainly express a desire for renewal, but also hostility towards all parties (right and left). This boils down to the libertarian parody of the slogan, “el pueblo unido jamás será vencido” (The people united will never be defeated) becoming, “El pueblo unido avanza sin partidos” (The people united advances without parties). Here there are right-wing populist candidates, but above all many endearing personalities, sometimes sincere, who have aroused support, without television media and without a campaign budget. The right ran with candidates driven by fake accounts on social media networks, and on the left, a candidate in Santiago campaigned using the dating network Tinder.

These newcomers will have an impact in this 155-member assembly, with 58 independent elected officials (including Mom Pikatchu, icon of the October 2019 demonstrations), 25 of whom are far to the left.

Recomposition to the left

The third factor was the change in composition of the left, favoring the Communist Party of Chile six months before the presidential elections, with mixed results. The communist activist Irací Hassler (an economist of 30 years focused on student struggles) took over the city council of the municipality of central Santiago from the hard right’s Renovación Nacional’s d’Alessandri. The conservative newspaper, El Mercurio, was astonished by Hassler’s victory, and the wealthier neighborhoods are sounding the alarm (warning of the arrival of Chilezuela, the contraction of Chile and Venezuela, in reference to the Chavist regime accused of all evils by the Latin American bourgeoisies).

But the coalition that brought Irací Hassler to municipal power includes the Communist Party, the Social Green Regionalist Social Federation, and the Frente Amplio (Broad Front), the latter of which officially made a pact with those who crafted the repression that saved the regime after the social outburst and mass mobilizations at the end of 2019. This same Frente Amplio voted for the “anti-slum” laws that still keep thousands of young people in prison today. On the other hand, Daniel Jadue, communist presidential candidate, won the popular city of Recoleta (in the agglomeration of Santiago) with 65%, and seems to be the focal point of the upcoming recomposition of the “responsible” left.

Popular abstention

Finally, we must mention the popular abstention, which was massive. Abstention was estimated to be 60% at the national level and exceed 80% in the poor neighborhoods of the big cities. Overall, class composition played a big role in how the sectors driving the protests acted. The politicized and unionized circles, which were generally more organized, saw more activity in the elections, while the popular working class circles, and especially the youth, expressed their distrust of any intermediate institutional solution. This shows an enormous potential that has not expressed itself fully. The pandemic has certainly suppressed social anger, but the ongoing social collapse and growing inequalities are fueling the new outbursts of activity to come.

The Trotskyist far left

Trotskyist groups in Chile are small collectives that rarely exceed a hundred activists and sympathizers. None of them have a national existence yet. They approached the Constituent Assembly elections according to two perspectives: that of the declared list in their own name for some, or that of an independent candidacy with broader support for others.

The Workers Revolutionary Party (PTR), linked to the Trotskyist Fraction whose comrades we know in France as the CCR-Permanent Revolution, and in the U.S. as Workers’ Voice, chose the first option and achieved some notable successes, as in Antofagasta, an important port and mining city in the north, (with 13% of the vote in the municipal elections and 7% for the Constituent Assembly), and more than 50,000 votes nationally (with an electoral body of 8 million).

Other groups have chosen the second approach, such as the Anti-Capitalist Movement (linked to the international current of the International Socialist League, resulting from the crisis of the Morenoist movement) who presented candidates supported by teams of militants not aligned with a party, with very limited means, and obtained 2% in two constituencies. But it was above all the election of Maria Rivera, recognized activist and lawyer of the International Workers Movement (Chilean section of the International Workers League (LIT), linked to the PSTU of Brazil) to the Constituent Assembly, in the eighth largest constituency of the country, with 4.13% of the votes to her name, that created the surprise. These comrades put all their forces in one sector, with a candidate who is recognized and esteemed for her courage, in an independent candidacy, supported by activists and sympathizers and then several collectives, but which showed very clearly its program and social camp. These modest successes are a step forward for all revolutionary activists in the country and pave the way for future goals.

Prospects

Beyond these surprises, where is Chile going? For now, the existing institutions are trying to determine that answer, but the importance and scope of this question should not be underestimated. These elections echoed the revolt of 2019. The lessons learned during this cycle of struggles has made it possible to condemn, even at the institutional level, the “democratic” trap that sought to divert the social momentum toward the ballot box. The passive blockade through the electoral path created a surprise, but above all it has given time to those who are looking for a way out of both the legacy of the dictatorship and the social crisis. Democratic and social questions are closely connected in working class circles, as we well know, and the people can’t eat declarations on paper. The time for half measures is over.

So the time has come for reorganizations. Of course, we face barriers with the institutionalized left and the Communist Party that rely on the social and trade union establishment to co-opt and moderate our struggles. People have yet to learn that Popular Fronts only lead to dead ends. Revolution, and even social reforms, will not be carried out without the brutal opposition of a determined bourgeoisie, whose social base has not disappeared with the electoral failure of the right.

But we may also see a possible reorganization of a revolutionary force whose time has come, with small but not isolated Trotskyist organizations and thousands of popular collectives. It will be an immense task at a time when the whole continent is set in motion.