When Durham School System announced that 1,300 “classified staff,” (janitors, IT workers, teachers’ aides, and cafeteria employees) would receive a seven percent wage increase, one delighted worker told a local newspaper, “We’re starting to get the pay we deserve.” Workers began to receive paychecks reflecting the raises on Oct. 31.

During the MLK holiday weekend (Jan. 13-15), school officials emailed staff members, announcing that the school administrators had miscalculated the money available for staff salary increases, and cancelled the raises. The School Board decided to dock staff paychecks over the next three months for what the Board called “overpayments.” Then paychecks would be recalculated for the remainder of the year, with raises much less than the promised 7%. Salaries for teachers were unaffected.

On Wednesday, Jan. 17, Durham schools were thrown into chaos when a large minority of both bus drivers and cafeteria workers called in sick. The School Board backed off from immediately docking paychecks, but continued to insist a lack of funding required pay cuts. During the next ten days, angry staff, teachers, and supportive parents rallied and protested at meetings of the Durham School Board, which didn’t budge from its plan to cut wages in the course of the school year.

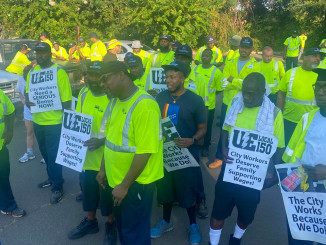

During 2023, the Durham Educators Association (DEA) carried out a successful organizing drive among teachers and classified staff. The Association now represents 65% of the 3,500 non-management employees in the school system. The DEA demands no pay cuts and “a seat at the table” in discussions to resolve the crisis. On Saturday, Jan. 27, about 100 union activists and officials met all day to plan future action. It is illegal for public sector workers in North Carolina to strike, but there was plenty of support for calling in “sick.”

The following Wednesday, Jan, 31, 12 schools didn’t open on account of staff and teachers calling in “sick” for the day. Hundreds of teachers, staff, parents, and students rallied that afternoon at the board’s headquarters. On Monday, Feb. 5, a one-day sickout closed seven schools that had not participated in the Jan. 31 sickout.

On Friday Feb. 9, a large percentage of the “Classified Staff” in the Transportation Department stayed off the job, acording to officials of the School Board. Consequently the School Board called off all classes because 75% of the students depend on the school buses. School Board officials closed the schools again on Monday, Feb. 12, giving the same explanation.

The DEA said it had no responsibility for Friday’s system wide closure, and questioned the reason for it. At the present time, DEA says it has no plans to call another “Day of Protest.” That could change if the Feb. 20 meeting of the County Commissioners doesn’t produce a solution satisfactory to the teachers and school staff.

The School Board has no taxing power of its own. Its budget depends entirely on appropriations from the state and the county as well as U.S. Department of Education grants. The School Board has so far not publicly asked the County Commission to appropriate any additional money to fund the salary increases promised to the classified employees, leaving the Board with no options to pay the promised salaries except to shift $10 million from some other part of the $734 million budget. Union members are organizing a rally at the emergency joint meeting of the School Board and the County Commission set for Feb. 20. School administrators and some board members have begun to meet with leaders of the DEA, but no agreement has been reached to end the crisis.

In North Carolina, public sector workers who strike risk a four-month jail sentence and a fine. It is illegal for any public agency, such as school boards, city governments or counties, to negotiate contracts with unions. Unions of public sector workers are beginning to grow in North Carolina. Unions can organize rallies and lobby public officials who set budgets. Some North Carolina state agencies and a few of the larger cities have agreed to “meet and confer” periodically with unions representing a significant number of their workers, but this is far from satisfactory to workers.

Public schools in North Carolina are increasingly underfunded as the state government, dominated by extreme right-wingers, shifts money to charter schools. In the not-too-distant future, there will be little left of K-12 public education in North Carolina unless teachers and support staff throughout the state find ways to stop the drive for privatization. If Durham workers force Durham County politicians to cancel the threatened wage cuts, their victory could encourage public sector workers across North Carolina to think about what collective action on a state-wide basis could accomplish.