June 20, 2022

From the publication of the Etincelle fraction in the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA), Comrades of Speak Out Now, Translated from French

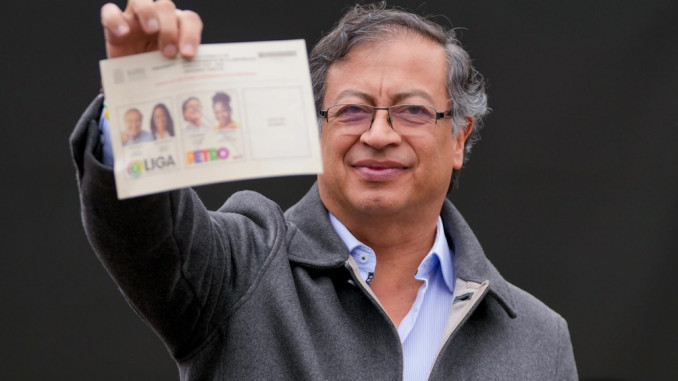

The Colombian election on Sun., June 19, of President Gustavo Petro and Vice-President Francia Márquez was a shock to the Colombian oligarchy. This was a close victory (50.69%) but very symbolic in a country that has never known a left-wing government over its two centuries and where, as the writer José María Vargas Vila pointed out more than a century ago: “the dictators of this country dip their daggers in holy water before killing.” This electoral victory follows the social explosion of April 2021, which saw millions of working-class Colombians occupy 21 cities (with an insurrectionary situation for weeks in Cali). It is also part of an electoral cycle that, on a continental scale, has seen left-wing presidents take office in July 2021 in Peru, in March 2022 in Chile, and perhaps soon in October in Brazil.

A polarized campaign

The first surprise was the ouster in the first round of the conservative right, led by Federico Gutiérrez. At the head of a coalition – in the shadow of Álvaro Uribe, the former president linked to the most conservative and violent sectors of the Colombian bourgeoisie, but also to the paramilitaries and drug traffickers – the candidate favored by the business community was unable to qualify, winning a modest 18% of the vote. Next, Rodolfo Hernández Suárez, a tropical Donald Trump, a populist businessman who made his estimated $100 million fortune in real estate, took the seat to represent the continuity of the regime with an anti-system stance that was backed heartily by social networks. On the other side, the left was represented by Petro, a former Guevarist activist and follower of liberation theology and the M19 (Marxist 19th of April Movement) and Márquez, an Afro-Latina feminist activist. This duo contrasted starkly with the supporters of the dirty war against the armed opposition of the FARC and the business community. The left-wing coalition had the support of the left-wing parties and a majority of associations for struggle and social change, but it extended its alliances far and wide by including the former right-wing mayor of Medellín, conservative Christian leader Alfredo Saade. In the end, this is not surprising. After all, Gustavo Petro was Mayor of the capital, Bogotá, from 2014 to 2015, weaving ties he had already well developed during his long career as a deputy.

A deeper meaning

But to reduce this election to an ordinary alternation between parties in power is insufficient. Significant sectors of popular collectives, and sometimes even the most radical among the fighters of the Primera Linea (the “front line” fighters against the regime, in 2021), as well as an significant part of the population, wanted to turn the page on the permanent civil war imposed by the oligarchy and emerge from a major social crisis. In a country where the richest 10% own 65% of the wealth, with 39% of the population living below the poverty line (and a million more having become poor as a result of the effects of the pandemic), a high infant mortality (already 14 per 1000 in 2018), galloping inflation of 9% in April, there is no shortage of reasons to try something else[1]. Colombia has become deindustrialized (11% of its economy depends on this sector), and growth depends on mineral exports and construction. But the future Petro government will come to power in a context of contraction and a disruption of commodity prices.

A very timid program

Yet Petro’s program includes no nationalizations or any measures that would even symbolically curtail the power of the mighty oligarchy. His program has put forward a moderate tax reform, a policy of boosting employment through state orders, even promising in his electoral platform: “The state will ultimately employ those who do not find solutions in the private sector.” To be fair, he also promises a demilitarization of civilian life, putting an end to compulsory military service, reducing the army budget (which today represents 3.4% of GDP), or, more boldly, the dismantling of ESMAD (a sort of combination of military police and anti-terror squad), much criticized during the social protests for its brutality. The left-wing guarantee of this new government is embodied by the vice-president who, by her very presence, recalls an African past that has been hidden for too long in Colombia. A feminist and environmental activist (she courageously opposed the devastation of the gold mines in the Suarez district), and from Medellin where she led her campaign, she essentially insisted on the establishment of a Ministry of Equality, putting forward the demands of the women’s movement, of sexual diversity, as they say in Latin America, and of the youth: timid proposals that will probably not be able to pass the institutional stage of the Senate and the House of Representatives, where the right wing dominates.

A fierce and determined bourgeoisie

The army threatened to carry out “its responsibilities” in case of victory of Gustavo Petro and Francia Márquez, and thousands of left-wing activists were threatened directly on the eve of the second round. There were published lists of the names of Primera Linea militants, thuggish visits to the neighborhoods of militants or supposed militants, and increased pressure on combative unionist circles (through pressure, and dismissals). The oligarchy, fearing a new social explosion, is openly preparing for a confrontation with a moderate left that is not prepared for the shock. The fact that on the evening of the second round, Petro called for a government of national unity, including the hard right around Uribe’s successors, will likely not calm a bourgeoisie that is used to doing the worst. With a growing social crisis, as evidenced further south in neighboring Ecuador by the riots of this past weekend, the test of power for the legalist and institutional left looks bitter.

[1] Inflation in Latin America, based on a typical shopping bag of food, plus housing and energy, is estimated to be close to 40% per year, and it is higher in Peru, Mexico, Brazil and Paraguay.