On a cold Sunday, the 22nd of January, 1905, tens of thousands of workers in St. Petersburg, the capital of Russia, marched to the Tsar’s splendorous Winter Palace to deliver a petition.

This simple action led to a massacre known as Bloody Sunday, and was the beginning of the 1905 Russian Revolution. It was on this day and in the following months that, for largely the first time, large numbers of Russian workers and peasants learned clearly that the Tsar was not their friend, but rather one of their oppressors. And in the same moment they began to realize their power as a class to change not only the conditions of their daily lives, but their power to change the world!

The Background

Since the 1870s, Russia had undergone rapid industrial development, particularly in its major cities of St. Petersburg, Moscow, Baku and others. Although still largely a poor, underdeveloped empire of peasants living miserable, spartan lives, these major cities became crowded, unhealthy, miserable settings of exploitation. Workers worked eleven or more hour days, six days per week, performed manual labor long since obsolete in more advanced western capitalist countries, lost body parts in factories, and lived in cramped, uncomfortable conditions.

For years they had spontaneously rebelled, attempted to form small, localized unions, and some even joined radical political organizations like the Narodniks, the People’s Will, or the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. But these groups remained small, and had little influence on the growing mass of workers.

The Day

That all changed in 1904 St. Petersburg, when dozens of activist workers and a Priest named Father Georgi Gapon organized a workers organization called The Assembly of Russian Workers of St. Petersburg. Gapon was encouraged and influenced by tsarist officials, who wanted a reformist workers body that could

“direct their grievances into the path of economic reform and away from political discontent“and “wean the workers away from radicalism.” In other words, the organization was meant to be tightly controlled to keep the workers passive.

Despite these limitations, the Assembly provided a means of solidarity for working people, hence grew in membership to at least 2,000 by 1905. It was at that point that the workers themselves, in response to the conditions of their lives and work, pushed the organization toward more radical change, and toward a more confrontational posture toward the tsarist regime.

On January 3, a handful of workers were fired from the massive Putilov iron and machine works, one of St. Petersburg’s largest factories. Gapon and the Assembly demanded their rehiring, and a strike began. The initial demands, including an eight hour workday and improved working conditions, grew into more political demands including the right to freedom of speech and assembly. By January 7, 140,000 workers were on strike. Although it ended a few days later, the strike had affected hundreds of thousands, giving them a glimpse of how they could build their power.

According to Leon Trotsky, in his brilliant and detailed analysis of the 1905 Revolution, it was at this point that “social democrats moved to fore.” By social democrats, he meant the socialists of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. These militant activists helped shape the development of the famous petition that the marchers would attempt to deliver on January 22.

The petition – in the most deferential tone possible – asked for a variety of legal, political, and workplace and labor reforms that would alleviate some of their suffering. It called the Tsar “Sovereign,” and pleaded with him to protect them from the “bureaucrats” and “employers” who exploited them. Despite the deferential tone, however, it demanded significant changes that, if enacted, would have challenged the very basis of the Tsar’s rule. Most specifically, it asked him to call a Constituent Assembly that could usher in a new democratic era in Russia in which their voice, and the voice of the poor peasantry, could at least be heard. Obviously, the Tsar and the Russian feudal lords could never allow such a concession.

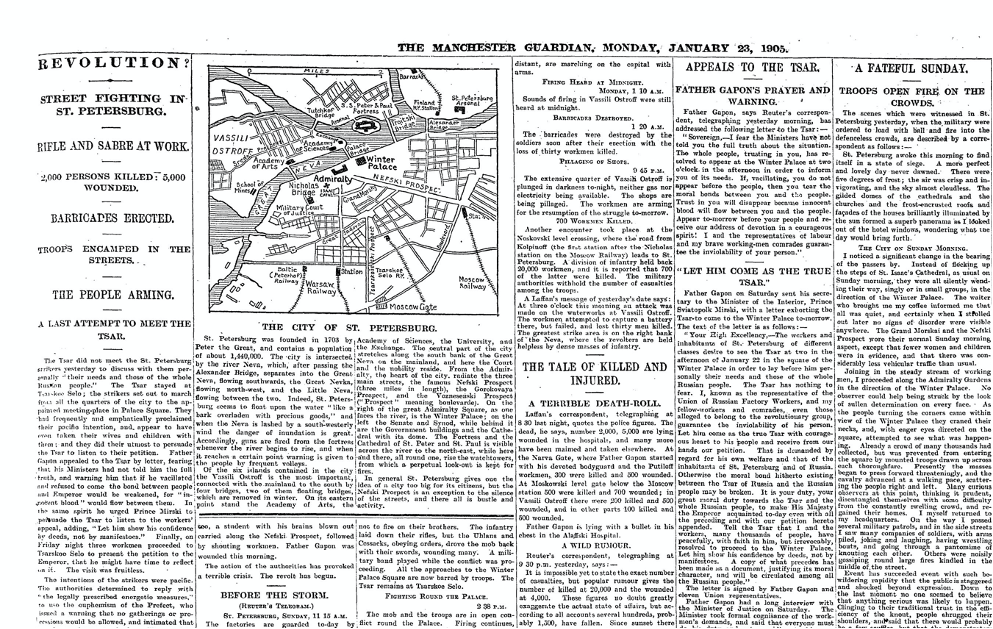

The petition – signed by 150,00 – was never delivered. Instead, on January 22, St. Petersburg police, Russian army troops, and horse mounted Cossacks attacked the marchers at different points in the city, shooting many in open squares, slashing others with swords in cavalry charges. With estimates of those killed varying so widely that it is impossible to cite an accurate number, at least hundreds were killed and at least thousands were wounded in hours of urban warfare in the Russian capital.

Sunday, January 22 has since been known as Bloody Sunday. Its violence is emblematic of the historical exploitation and oppression faced by Russian workers and peasants throughout the centuries.

Yet it is also a turning point, a moment at which workers and peasants chose not to accept their oppression, but instead to begin to challenge their oppressors for control of their society! And they learned also that the Tsar was one of their oppressors, no different from the powerful landowner or the wealthy factory owners who directly exploited them! V.I. Lenin, one of the leaders of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, wrote that “The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence.”

What Followed

Not only did the massacre awaken the consciousness of the workers and peasants to their true oppressors, it also triggered an expanded a nationwide general strike that grew into what is now considered the first Russian Revolution. In the days and weeks following the massacre, word of the bloodletting spread and anger exploded. First city electric utility workers went on strike. Then print workers. Then the sailors in the Kronstadt naval base guarding the waters to St. Petersburg. Then a general strike. Then railroad workers, who spread it outward. Then miners. And on and on. One city and one town at a time, a general strike fanned out across the empire. These lasted a month or more, then subsided, only to be replaced by a new general strike a month or two later.

Leon Trotsky’s description captures the wavelike development of a strike turning into a revolution:

“The strike began confidently to take over the country. It finally bade farewell to indecision. The self-confidence of its participants grew together with their number. Revolutionary class claims were advanced ahead of the economic claims of separate trades. Having broken out of its local and trade boundaries, the strike began to feel that it was a revolution – and so acquired unprecedented daring.”

And, in the midst of these surging revolutionary waves, the Russian workers pioneered a new organization – the soviet! The soviet, or workers council, was created in early October as a body that would unite workers from different trades and different political parties into one body. It was meant to represent one class and one class only: the working class. Organized in St. Petersburg, it took the name Soviet of Workers Deputies, and immediately took on an array of activities: calling strikes, facilitating communication between workers organizations, demanding policy changes from the city government, addressing supply of food and goods, making public proclamations on behalf of the working class, and organizing defense of factories and workers on strike. While many representatives were unaffiliated workers, others were Menshevik and Bolshevik members of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. It was the first democratic organ of the working class in Russian history.

The Revolution, though a huge upsurge, slowly tired under the forces of economic necessity and a combination of tsarist repression and weak reforms. In November, members of the Soviet of Workers Deputies were arrested and sent into exile. In December, a final workers uprising in Moscow was violently crushed and the 1905 Revolution was over.

The Significance of Bloody Sunday

The Revolution of 1905 heralded the dawn of a new day. Not only had workers and many peasants and soldiers lost their illusions about the Tsar and gained a new sense of solidarity, they also developed new tools to build their power and challenge the oppressors and oppressive systems that shaped their lives: the general strike and the soviet. Both of these would be used twelve years later, in the successful Russian Revolution of 1917.

And it was all triggered by Bloody Sunday. The deaths of hundreds of workers in St. Petersburg on that cold day, although tragic, awakened workers and peasants and even soldiers to the potential in their own power, and taught them how to use it.

Bloody Sunday 1905, a tragic day of huge significance.